Participating in parliamentary democracy

THE current furore over “Section 28” (more properly in Scotland, Section 2A of the Local Government Act 1986) raises a number of important constitutional issues for the Scottish Parliament. How far are MSPs representatives who decide issues according to their own consciences? How far should public opinion influence these decisions? What is public opinion anyway when one side of the argument is backed by major and disproportionate funding? What indeed is the true nature of democracy in modern Scotland? How far is there an electoral mandate for particular policies?

The Scottish Parliament was designed to be physically closer to the people, and to be more responsive to the popular will. A fair system of election would accurately reflect the political balance of the nation; open government and an accessible Parliament would empower people to have their say in policy decisions; powerful Parliamentary Committees would hold the Executive to account in front of the country; there would be a right to petition Parliament directly through the Petitions Committee and civic society would have a major input through the Civic Forum and participation in Committees.

All good stuff, but raising new dilemmas which were often not foreseen by our founding fathers.

Electoral Mandate

Student tuition fees were brought in by the Labour Government in 1997 without any form of electoral mandate. The Scottish Parliament elections in 1999 elected a substantial majority of MSPs opposed to fees. As a result of the proportionate voting system and the Parliamentary arithmetic, the Liberal Democrats were able to achieve the abolition of fees, thus vindicating the mandate of the electorate and proving the superiority of the Scottish Parliament system.

This type of democratic argument plays less well with issues like Section 28. I rather doubt that most people had ever heard of Section 28 until recently, and rational debate on solid facts is rather scarce. However, the consultation process on the Ethical Standards in Public Life etc (Scotland) Bill should put the repeal of Section 28 into perspective and allow proper examination of the issues raised.

A plague of petitions

The Petitions Committee is right in the firing line too. It has been swamped by petitions on every subject known to man - and one man in particular! A certain Frank Harvey at the latest count had 29 petitions to his credit. And beyond Mr Harvey is a growing tide of petitions against the supposed evils of Councils and Housing Associations, Governments and Quangos. Scottish Petitioners have become “the throng of common suitors that follow Caesar at the heels and crowd a feeble man almost to death.”1 Not surprisingly the Petitions Committee is looking at how it might restrict the flow!

Warrant sale bill

The Parliamentary Committees are now developing a confidence and esprit de corps of their own - which pays no particular deference to traditional organisations or preconceptions, as our own Law Society delegation found out when it gave evidence to the Social Inclusion Committee on the Warrant Sale Bill. It may very well be that our system of debt enforcement relies ultimately on the threat of poinding and warrant sale rather than the few such diligences actually executed, but the Parliamentary Committees were more impressed with the fact that actual warrant sales rarely recover the debt, and that many of those threatened with diligence genuinely cannot afford to pay.

Whatever the implications for recovery of consumer or commercial debts, it is summary warrant procedure for recovery of council tax which is the central issue. The poll tax debacle stands as stark warning of the long-lasting consequences of bad legislation - rather like the after-effects of prohibition in America. The mill-stone of accumulated poll tax and council tax arrears threatens to drag down the whole system.

From contract to social policy

“The movement of the progressive societies has hitherto been a movement from Status to Contract.” This famous dictum of Sir Henry Maine in 18612 has in large measure been reversed in recent years to become a movement from laws based on freedom of contract to laws based on social policy. Where “the average instinct of justice in the ordinary man”3 would recognise a wrong, there should be a remedy.

This instinct of justice is producing increasing pressure for action on a variety of good causes. Public concern about the level of domestic violence was able to obtain a magnified focus following effective public lobbying of the Parliament. The case for empowering profoundly deaf people was boosted by a members’ debate calling for recognition of British Sign Language as an official language. The Housing Bill due this summer will rightly raise great expectations of action on homelessness and tenants’ rights in particular.

In short, the Scottish Parliament is hastening the reconnection of law to justice and popular equity, but it must become robust enough to discriminate effectively between the causes advocated by different pressure groups, and to set its own priorities reflecting the sense of the nation. How it goes about this will affect the nature of Scottish constitutional law for the future.

- “Julius Caesar” by Shakespeare

- “Ancient Law” by Sir Henry Maine (1861)

- “Law in the Making” by C.K. Allen (1927)

In this issue

- President's report

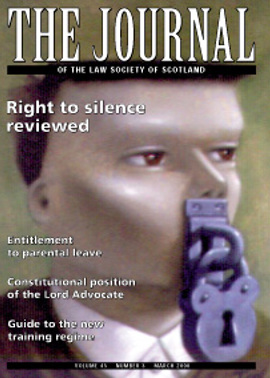

- Self-incrimination still a grey area

- The constitutional position of the Lord Advocate

- Right to parental leave begins

- Essential guide to the new training regime

- Participating in parliamentary democracy

- Why conspiracy charge was not objectionable

- Update on workers and the EU

- Common risk themes, common solutions

- It's litigation Jim but not as we know it