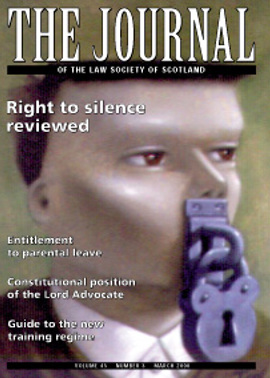

Self-incrimination still a grey area

Section 172 of the Road Traffic Act 1988 is a statutory provision, derived ultimately from Section 113(3) of the Road Traffic Act 1930, which gives the police the power, when the driver of the vehicle at the time is alleged to have contravened specified provisions of the Road Traffic Act, to require the registered keeper of a vehicle to advise them as to the identity of the driver of that vehicle at a particular time. Failure to give such information when so required itself constitutes an offence, unless the keeper can show that he or she did not know, and could not with reasonable diligence have ascertained, who the driver was at that time.

The keeper of the vehicle has no domestic law right to remain silent in the face of such questioning and if he identifies himself as the driver that reply can be used in evidence against him.1 In Margaret Anderson Brown v Procurator Fiscal, Dunfermline2, the accused had admitted, when questioned under Section 172 of the 1988 Act, that she had been the driver of the car of which she was the registered keeper at a time when the evidence from a subsequently administered breathalyser would have shown her blood alcohol level to be in excess of the permitted limits.

It was argued on behalf of the accused that any attempt by the Procurator Fiscal to rely on her Section 172 reply which, in accordance with normal practice, had been given without the benefit of a prior caution but at a time when she was already suspected of having driven her car after consuming an excess of alcohol, would contravene her Convention rights to a fair trial guaranteed by Article 6(1) ECHR. This claim was raised by the accused’s solicitor as a preliminary devolution issue going to the competency and relevancy of the drink driving charge. The devolution issue was rejected by the sheriff and the matter was then appealed to the Appeal Court of the High Court of Justiciary where it was considered by a three judge court made up of the Lord Justice-General, Lord Marnoch and Lord Allanbridge. At the appeal, in addition to junior counsel for the accused and the Solicitor General appearing for the Crown, counsel for the Advocate General for Scotland was given leave to appear, despite her not having intervened or been represented in the court below.

The Lord Justice General expressed the view that the appropriate manner of proceeding in such cases where Convention rights were prayed in aid against provisions of primary Westminster legislation was for the following steps to be followed:

Firstly, the court was to “identify the scope” of the Convention right or rights relied upon in the circumstances of the case;

Secondly, the court should consider whether the statutory provision at issue was, on its “established construction”, compatible with that Convention right. If it is then the established construction may be applied.

If, however, the established construction is found to be incompatible with the Convention right relied upon in the case, the court should then turn to consider whether or not the statutory provision could nevertheless be “read down” so as to make it compatible with the Convention right (see Section 3 of the Human Rights Act 1998);

It is only where the statutory provision of or made under primary Westminster legislation cannot be read or given effect to in a way which is compatible with the Convention rights that a public authority may rely on Section 6(2)(b) of the Human Rights Act, and give effect to or enforce the national provisions, notwithstanding their incompatibility with the Convention. If the court is satisfied that the provision cannot be remedied or read down so as to make it compatible with the relevant Convention right, it may then make a “declaration of incompatibility” under Section 4(2) of the Human Rights Act 1998. Section 4(6) provides that any such declaration of incompatibility will not, however, “affect the validity, continuing operation or enforcement of the provision in question and is not binding on the parties to the proceedings in which it was made”. It is therefore of no assistance to the person challenging the national provision. As the Lord Justice General put it in this case, “irremediable incompatibility assists the Crown”.

The arguments presented to the Appeal Court

The accused argued in support of her appeal that Article 6(1) ECHR which provides, so far as relevant, that “in the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law”, implicitly contained within its terms a right to remain silent under police questioning and a privilege against self-incrimination. The accused relied in support of this claim on general observations on the right to silence and the privilege against self-incrimination which were contained in the following decisions of the European Court of Human Rights: Funke v France3, where the Strasbourg Court found that the imposition of fines by the French customs authorities against an individual in respect of his failure to disclose documents concerning financial transactions violated Article 6(1) ECHR; Murray v United Kingdom4, in which there was held to be no violation of Article 6(1) ECHR where adverse inferences of guilty were drawn from the fact that the accused exercised his right to silence after being found by the police in a house in which an IRA kidnap victim was being detained; and Saunders v United Kingdom5, in which the use at a subsequent fraud trial of transcripts of the evidence taken from the accused by DTI inspectors acting under compulsory powers in relation to the investigation of company takeovers under compulsory powers was found to contravene Article 6(1) ECHR.

By contrast, the respondents referred to a variety of comparative human rights material taken from a number of jurisdictions within the common law English speaking legal world. In addition the respondents were able to point to a number of decisions of the European Commission of Human Rights in which it rejected as “manifestly ill-founded” claims by applicants that their Article 6(1) ECHR rights had been breached. These included the following situations specifically involving road traffic regulation: where an individual was required under UK law to produce blood samples under threat of prosecution in a drink driving case;6 where a car owner was found liable in the Netherlands for parking fines in respect of his car when he was not able or willing to name the driver or to establish that the car had been used against his will;7 where an Austrian national regulation obliged the registered keeper of a car to accept responsibility for the unlawful use of his car, or to name the actual driver if known to him;8 and where the registered keeper of a vehicle was fined by the Spanish authorities for failing to disclose the identity of the driver of his vehicle after it had been caught in a radar speed trap9.

The decision of the Appeal Court

The Lord Justice General noted, in a judgment concurred in by Lord Marnoch and Lord Allanbridge, that it was not easy to discover the scope of the right to silence protected under the European Convention simply from the judgments of the European Court of Justice since there were not many of these. He derived little guidance from the admissibility decisions of the European Commission of Human Rights noted above, holding that “not all of the[ir] reasoning is easy to follow” and that, in any event, “none of the decisions concerned the use of any reply as evidence at a trial”. He held that it was “legitimate for this court to supplement any guidance to be derived from the decisions of the [Strasbourg] Court itself by having regard to constitutional texts from other countries and to decisions of their courts on the interpretation and application of those texts.” Extensive reference was made to recent decisions of the supreme or constitutional courts of Canada, South Africa, and the United States of America as well as to older Scots and English authorities expounding the pre-statutory common law. He concluded:

“According to recognised international standards, to be effective, the right of silence and the right not to incriminate oneself at trial really imply the recognition of similar rights at the stage when the potential accused is a suspect being questioned in the course of a criminal investigation. In particular the accused’s right to silence and not to incriminate himself under the Convention would be infringed if the Crown could lead evidence of an answer which the accused was obliged to give in response to police questioning in those circumstances. To hold otherwise would be to undermine the central right of an accused under the Convention not to incriminate himself at trial.”

He held that Article 6(1) ECHR accordingly conferred “testimonial immunity” on any verbal statements an accused was required to make under compulsion. Citing case law of the Strasbourg Institutions10, and of the US and Canadian Supreme Courts, he found that the right to silence and the privilege against self-incrimination “does not extend to the use in criminal proceedings of material which may be obtained from the accused through the use of compulsory powers but which has an existence independent of the will of the suspect such as inter alia, documents acquired pursuant to a warrant, breath, blood and urine samples and bodily tissue for the purpose of DNA testing.” The Lord Justice General Court then noted as follows:

“The Solicitor General argued in terrorem that, if we were to allow the appellant’s appeal, then any use of information obtained under Section 172 at trial would infringe an accused’s right not to incriminate himself under Article 6(1). He pointed out that this could have momentous effects on the use of roadside cameras in the detection and prosecution of road traffic offences, since such prosecutions rely on the use of Section 172 for proof of the identity of the driver. That may or may not be so, but, in accordance with the guidance of the [Strasbourg] Court, I have reached my decision on the facts of this particular case. I have not considered the facts of other possible cases. But not all the features of the present case would be found, say, in cases where the police send out a written request to the keeper of a vehicle caught speeding by a roadside camera. I therefore reserve my opinion on such a case until it arises for decision.”

Section 172 of the Road Traffic Act 1988 was therefore read down in this particular case to mean that while the police may still lawfully require a person to answer questions as to the identity of the driver of their vehicle, any reply which might tend to incriminate the maker of the statement cannot then be used in court proceedings against them. The court accordingly pronounced a declarator to the effect that in the circumstances of this case, the procurator fiscal had no power to lead and rely on evidence of the apparently self-incriminating admission which the appellant was compelled to make under Section 172(2)(a) of the Road Traffic Act 1988.

Conclusion

In expressly confining their finding as to the inter-relationship between the Convention and national law to the facts of the particular case before them, the decision of the Appeal Court may be thought to have raised very many more questions than it answers. It is hoped that perhaps more general guidance may be given by the Privy Council to which leave to appeal against the decision has now been given.11 Certain observations may be made at this stage.

Firstly, the Appeal Court appears not to have been referred to any material from the legal systems of any of the forty other Contracting States within the Council of Europe which are similarly subject to the Convention and under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights. It seems likely that similar questions to those raised in the present case have already been taken in other continental European countries where speed cameras and radar traps are ubiquitous. Such reference might have been of assistance to the Court.

Secondly, the Human Rights Act 1998 “domesticates” only certain specified provisions of the European Convention. In contrast to the position under European Community law it does not incorporate into UK law the whole of the jurisprudence of the Strasbourg institutions: instead, Section 2(1) of the Human Rights Act 1998 obliges UK courts only “to take into account”, among other matters, the relevant case law of the European Court of Human Rights and decisions and opinions of the Commission of Human Rights, and would appear to be designed to allow UK courts to develop their own Human Rights native culture12.

The Appeal Court in the present case however appeared to dismiss the non-admissibility decisions of the Commission of Human Rights as obscurely reasoned while elevating dicta of the European Court of Human Rights into binding pronouncements on the law. This approach might be thought to be perhaps both overly dismissive of the Human Rights Commission and overly deferential to the Strasbourg Court.

Thirdly, in their interpretation and application of the Convention to this particular case, the Appeal Court appear to have treated the Convention right in question not as a fundamental right, which is to say the starting point for any discussion to be weighed against competing public interests, but instead as an almost absolute individual right which trumps any competing general principles and considerations of the common good. Such a weighing of competing considerations in all the circumstances is arguably a necessary part of any application of a Convention right, and appears to be implicit within the doctrines of proportionality and the margin of appreciation which have been developed by the Strasbourg Court. In the meantime, pending the decision from the Privy Council, the advice to criminal solicitors is for the client to admit if asked by the police under compulsion that he or she was the driver at the time, since such a reply cannot be used in evidence against him or her, whereas a refusal to reply may still form the basis of a prosecution13.

- 1 See Foster v Farrell 1963 J.C.

- 2 Appeal No. 1652/99 Margaret Anderson Brown v Procurator Fiscal, Dunfermline, Appeal Court, High Court of Justiciary, unreported decision of 4 February 2000, accessible at www.scotcourts.gov.uk

- 3 Funke v France A/256-A(1993)16 EHRR 297

- 4 John Murray v United Kingdom A/593 (1996) 22 EHRR 29 at 60

- 5 Saunders v United Kingdom, A/702 (1997) 23 EHRR 313

- 6 Application 30551/96 Cartledge v United Kingdom, Commission decision of 9 April 1997, accessible at www.dhcour.coe.fr/hudoc

- 7 Application 61 70173 D N v Netherlands, unpublished decision of the Commission of 26 May 1975

- 8 Application 15135/89 JP, KR and 611 v Austria Commission decision of 5 September 1989, accessible at www.dhcour.coe.fr/hudoc

- 9 Application 23816/94 Tora Tolmos v Spain Commission decision of 17 May 1995, accessible at www.dhcour.coe.fr/hudoc

- 10 See for example, Application 27943/95 Abas v Netherlands, Commission decision of 26 February 1997, accessible at www dhcour.coe.fr/hudoc

- 11 See for example the speech of Lord Hope in R v Director of Public Prosecutions, ex parte Kebilene (1999) 4 All ER 801, HL at 840 to 850 for a full discussion of the implications of the Article 6(2) ECHR presumption of innocence on a wide variety of statutory provisions

- l2 Compare with the apparently more sceptical approach taken to the Strasbourg court’s case law, in particular its ready reliance in immigration matters on the state’s “margin of appreciation” which was taken by the Lord Ordinary in Salan Abdadou v Secretary of State for the Home Department, 1998 SC 504, OH per Lord Eassie at 518

- 13 See now R v Hertfordshire County Council, ex parte Green Environmental Industries Ltd and another, HL unreported decision of 17 February 2000 (accessible at www.parliamentthe-stationeryoffice.co.uk) for recent confirmation that European Human Rights jurisprudence gives no authority to individuals to refuse to answer potentially incriminating questions at the stage of pre-trial investigation. See, to like effect, Serves v France 20 Oct 1997, RJD 1997-VI no. 53, (1997) 28 EHRR 265

In this issue

- President's report

- Self-incrimination still a grey area

- The constitutional position of the Lord Advocate

- Right to parental leave begins

- Essential guide to the new training regime

- Participating in parliamentary democracy

- Why conspiracy charge was not objectionable

- Update on workers and the EU

- Common risk themes, common solutions

- It's litigation Jim but not as we know it