Why conspiracy charge was not objectionable

Self-incrimination

Do you, for example, have to give your name to a police officer if formally required to do so? Careful attention is recommended to the case of Brown v Stott 2000 GWD 5-237, which is about self-incrimination arising out of a registered keeper being required under statute to disclose the identity of the person driving their car at a particular time. It is understood that this decision has been appealed and it may be that a lot of cases will have to be adjourned until such time as the matter is finally resolved.

Those with a penchant for schadenfreude may like to take a look at the case of Buchan v Stott 2000 GWD 4-169, in which the accused spent three days in custody as a result of his failure to give information.

Conspiracy

Cases on conspiracy and jurisdiction are not the stuff of everyday practice but may for that be all the more worth looking at. (The other point about HMA v Megrahi 2000 GWD 5-183 is that it is the first reported case to come out of the Lockerbie trial). Of the various points taken as matters of competency and relevancy, the most interesting is the one regarding the charge of conspiracy. It was argued on behalf of the accused that the charge was objectionable on the basis that a conspiracy is complete as soon as agreement is reached and the locations specified for this having happened were all outwith Scotland. The short answer to this is that conspiracy is a continuing crime until it is either abandoned or its purpose is fulfilled and if the purpose is to offend against the peace of the country then it is justifiable in that country.

Mixed statements

The question of mixed statements has come up again in the context of misdirection, through a failure on the part of the judge to follow the guidance given by the case of Morrison v HMA 1991 SLT 57. Irvine v HMA 2000 GWD 5-186 is a case in which the accused did not give evidence while the Crown led evidence of a statement made by the accused to police officers which could incriminate him but included a claim of self-defence.

This matter is often dealt with in a charge by the judge emphasising that evidence given in support of a special defence of self-defence may, taken along with the other acceptable evidence in the case, leave the jury short of being satisfied of proof of guilt beyond reasonable doubt. It was held that the jury might not have been made aware that the whole of the statement, being a mixed one, was admissible and it was also held that the sheriff had not made it clear that it was for the Crown to displace the accused’s explanation of self defence. It may seem odd that a plea of self-defence can succeed without the accused giving evidence provided that matter is raised in an admissible extra-judicial statement but there we are.

While I do not suggest that Morrison requires to be reconsidered, it does seem to be a troublesome decision and perhaps the whole law relating to extra-judicial statements and their value requires legislative attention.

Fair trial

There are three decisions of substance to be found in 2000 GWD issue 2, respectively numbered 41, 43 and 45. The first, McKenna v HMA, involves a devolution issue about the fairness of admitting in a trial for murder a statement by a possible co-accused who had since died. The minuter sought a ruling in advance that the admission of such statements as evidence would be oppressive, but the Appeal Court held that questions of what might or might not be prejudicial to a fair trial could, normally, only be determined in the light of proceedings as a whole and that in any case the court had a general duty, quite apart from the Convention, to ensure that a trial be fair both through addressing and deciding upon objections to the admissibility of evidence made during the trial and by giving proper directions to the jury as to what use might be made if such evidence as was admitted.

Articles 6(1) and (3) of the Convention, which guarantee a right to a fair trial, were invoked: it seems that because of the very broad way in which these sections are phrased that almost anything can be raised as an objection, though not of course with any guarantee of success, since the interpretation of the scope of the sections falls to be decided according to existing European jurisprudence rather than by what seems fair to the judge at the time.

Alternative verdicts

Mitchell v HMA was an appeal against conviction in a charge of murder and involved, among other things as a ground of appeal, the contention that the appellant’s case had not been properly presented by his counsel at trial. It may be unduly cynical to see this ground as something of a last resort and certainly one knows of cases in which it has been put forward on the basis of very limited and essentially inaccurate information given after a summary trial by a disappointed client to one solicitor about the perceived defects of one of his brethren from another firm.

Be that as it may, in this case the court held that there was no substance to the claim. It was also argued that the trial judge had been wrong to withdraw the possibility of culpable homicide from the jury’s consideration but as the court pointed out that neither prosecution nor defence had referred to this possibility at the trial.

This would seem to confirm the view that it is not necessary for a judge to direct a jury about alternative verdicts, which have not been raised by parties already, but the point is not without its difficulties and will no doubt depend on the precise circumstances. It might be the case, for example, though it does seem unlikely, that a judge in a murder trial took a different view from prosecution and defence about wicked recklessness and accordingly declined to direct that there was sufficient for murder (although sufficient for culpable homicide) although both sides had been proceeding on the basis that there was.

Duty to investigate

Finally of the three McDermott v HMA involves a discussion of what is meant by the provision of s36(10) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) which places upon the Crown a duty to investigate any defence which may be disclosed at a judicial examination.

Here an alibi had been disclosed and it was contended that the appellant had suffered as a result of the Crown not investigating it properly, since if they had some evidence might have been discovered which would have been of benefit to the appellant and would have had to be communicated to his advisors. It was held that this was the wrong approach to the sub-section. If the practice which was expected of the Crown as regards disclosure of evidence to the defence (see McLeod, Ptnr 1998 SLT 233) was taken along with a s36(10) it was clear that while the fact that the prosecutor had early intimation of a particular defence might result in an incidental benefit for the accused, there was not statutory duty to report to an accused the result of any such investigation and indeed not statutory sanction for failing to carry out such inquiries.

That being so, the section was found to be administrative in character and any question of what might or might not flow from any apparent failure was a matter to be dealt with at proceedings before the actual trial stage was reached.

It is not difficult to envisage the sort of difficulties which might arise at a trial if this were not the case: in particular it would create serious difficulties were the trial to involve a subsidiary question for the jury to decide as to whether or not the Crown had taken sufficient steps to discharge whatever duty might have been laid upon it in terms of the section.

Sentencing

Turning to sentences now, while one can only get a rough idea of what a proper penalty may be from previous criminal cases, some guidance is to be gained from the swatch of cases referred to in parts 36 and 40 of Green’s Weekly Digest 1999 and part 4 of 2000. General principles about consecutive sentencing may be derived from McVey v HMA (1928), and the possible consequences of attempted robbery with weapons involved from Findlay v HMA (1937). That the court will take a serious view of racially aggravated crimes may be seen from Hunter v Vannet 2000 GWD 4-141, which confirmed concurrent sentences of four months detention on a sixteen year old for two charges of acting in a radically aggravated manner towards two Pakistani shopkeepers.

While comparisons are often misleading, the case may be contrasted with the fate of another sixteen year old as disclosed by Duncan v HMA 2000 GWD 5-193, in which a sentence of nine months’ detention imposed for assault and robbery with a knife of a milk boy was successfully appealed and a disposal of probation and 200 hours of community service substituted.

Finally, some road traffic matters. The crime of causing death by careless, as opposed to dangerous, driving is one that we may still be having to evaluate properly, the main difficulty being the frequent disparity between the degree of carelessness and the extreme consequences.

If it be the case that causing death by dangerous driving was introduced in the first place because of a perceived reluctance on the part of juries to convict of culpable homicide (or in England manslaughter) in such circumstances, then the logical case for the lesser charge seems weak. It may be of course that juries recognising the serious consequences of causing death by dangerous driving are drawing away from convicting on that charge in cases in which they have some sympathy for the driver, but the compromise is not a happy one.

That the less grave charge can still be very serious is demonstrated by Gillies v HMA 2000 GWD 4-160, which saw the imposition of a sentence of five years imprisonment where there was also a question of driving under the influence of alcohol and of failing to stop and failing to report, the accused having a previous conviction for driving while over the legal limit. This indeed is the sort of sentence one might expect in a bad dangerous case.

The proposition that fixed penalties are productive of injustice (one of the main arguments against the “three strikes and you’re out (or perhaps in)” school of Home Office Criminology) often crops up when the totting-up procedure is being considered, as in Wilkie v McFadyen 2000 GWD 3-111.

Here there was put forward what at first sounds a formidable list of consequences said, cumulatively, to amount to exceptional hardship. It seems, however, that not all of them were established to the satisfaction of the court; the moral would seem to be that when the issue is to be raised, it is important to be able to produce the best proof possible to what the effects of disqualification would be.

Finally, lest there be any doubt about the matter, Milligan v Houston 2000 GWD 3-114, in which the question was whether the penalty imposed for speeding in a 30 mile zone was appropriate, is authority for the proposition that in such a case the justice is entitled in assessing the gravity of the offence to take into account his own knowledge of the locus.

(It will be observed that in this article there is frequent citation of GWD, which usually is most convenient at the time of writing. By the time of reading, of course, a fuller report in SLT or SCCR may have become available and in any case reports are now often immediately available via the Internet).

In this issue

- President's report

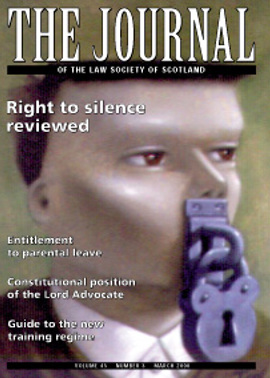

- Self-incrimination still a grey area

- The constitutional position of the Lord Advocate

- Right to parental leave begins

- Essential guide to the new training regime

- Participating in parliamentary democracy

- Why conspiracy charge was not objectionable

- Update on workers and the EU

- Common risk themes, common solutions

- It's litigation Jim but not as we know it