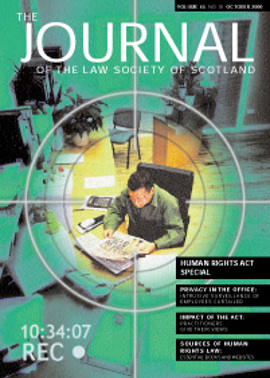

e-mail snooping RIP

Employers worry constantly about misuse of IT. Major companies such as Dow Chemicals, Orange, and Xerox have all sacked workers who allegedly downloaded pornography from the Internet. A new software (“Pornsweeper”) claims it can distinguish portraits in corporate web pages from other, more graphic, bodily images: skin tones and limb positions are apparently the secret! But how “legal” is it to snoop on employees,’ phone calls or e-mails?

The Interception of Communications Act 1985 (“ICA”) first regulated phone tapping on public phone systems. In 1997, a public sector employee’s “reasonable expectation of privacy” in making and receiving calls on office phone systems was established by Alison Halford, former Assistant Chief Constable of Merseyside, who said the police bugged her phone in a dispute over promotion. The European Court of Human Rights held this was a breach of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. But the legal regime that applies to monitoring employee communications in the workplace underwent a radical shake-up in October 2000. Now, both public and private sector employees will enjoy privacy rights for their workplace communications. Employers must grapple with three interlocking pieces of legislation.

The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (“R.I.P.”, appropriately) received the Royal Assent on 28th July. It repealed the ICA 1985. Much has been written about RIP’s controversial provisions requiring the disclosure of encryption keys to MI5 and the like. Internet Service Providers are alarmed at the cost of providing “black box” interception capability to GTAC, the laughably titled “Government Technical Advisory Centre” - in reality a new £25 million spy centre. Government says it should cost ISPs £20 million over the next three years to provide intercept capability to GTAC, and has promised some cash. Industry estimates range from £640 million to a somewhat unlikely £46 billion over the same period.

Sections 1(1) and 1(2) of the RIP Act make it a criminal offence to intercept communications on a private telecommunication system unless the system controller has consented. More significantly for employers, section 1(3) creates a delict of “unlawful interception of communications on a private telecommunication system by the operator of the system”. The wording is wide enough to catch telephone calls, fax messages, e-mails, and internet traffic. So now employers who seek to snoop on employees must establish the “lawful authority” of what they are up to.

“Lawful authority” can be established (a) by the use of a duly authorised interception warrant [RIP(Authorisations Extending to Scotland) Order 2000 No. 2418; RIP (Prescription of Offices, Ranks and Positions) Order 2000 No. 2417]; (b) by exercise of a statutory power for taking possession of information or property; (c) by establishing reasonable grounds for believing the sender and recipient have consented to interception [section 3(1)]; or (d) by having adopted a “legitimate business practice” authorised by the Secretary of State [section 4(2)]

The DTI thinks businesses are adequately protected by the “reasonable belief” exception to liability that operates where the business believes both sender and the intended recipient have consented to the interception. As to the absence of consent, the DTI on 25th July 2000 published its draft Telecommunications (Lawful Business Practice) (Interception of Communications) Regulations. These permit businesses to intercept without consent in only four broad circumstances:

- National security

- Prevention or detection of crime

- Investigation or detection of unauthorised use of a telecom system

- To provide evidence for the purpose of establishing the existence of facts or compliance with business practice or procedures.

The consultation period allowed by the DTI in relation to these important regulations was scandalously short and curiously ill-timed - a paltry four week period during July/August 2000 which as the DTI ought to have been aware is the holiday period for most businesses. Maybe DTI don’t take holidays? After protests, the consultation period was extended by three weeks, concluding on 15th September. All this could have been avoided if the substance of the regulations (less than one page of A4) had simply formed a schedule to the main RIP Bill earlier in the year.

The draft regulations are as controversial as the RIP Act. Do they mean, for example, that by pulling copy e-mails from an employee mailbox in response to a Specification served in court proceedings, the employer would be in breach of the RIP Act? The Legal Advisory Group of the trade organisation E-Centre UK has stated to the DTI that “it would be invidious if a business were under a legal obligation to disclose or produce documents, yet could not gain access to some of those documents without risking the commission of a delict under the RIP Act”. The Alliance for Electronic Business is concerned that where one member of a department is out of the office or unavailable, the current texts seem to prevent other members of the department accessing their colleague’s e-mail or voice mail in order to allow day to day business to continue.

October also saw the advent of the Human Rights Act 1998. Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights speaks of the right to respect for private and family life, home “and correspondence”. This Act binds the Courts, who must interpret the RIP Act, including the potential delict of unlawful interception, in the light of Article 8. Following the Halford decision referred to above, “respect” may mean employers having to make employees aware of telephone call monitoring, and give employees the ability to call and from work without fear of interception. Why should the same not apply to e-mail and internet access? Perhaps employers will have to provide a dedicated area where employees can telephone, send e-mail, and access the Internet, knowing that their activities will not be monitored.

Even after employers have justified the interception of communications under the RIP Act and taken account of the Human Rights Act, their troubles are not over. Any data recovered by legitimate snooping will undoubtedly constitute personal data under the Data Protection Act 1998. The processing of that data must be fair and lawful [Data Protection Act 1998, Schedule 1, Principle 1]. Snooping directed towards allegations of, for example, illegal distribution of porn files by employees, will generate Sensitive Personal Data attracting additional strictures under Schedule 3 the 1998 Act. Any e-mails captured during the snooping process will bear the names of sender and recipients, raising difficult issues of consent under both the Data Protection Act subject access provisions (section 7) as well as reasonable belief of consent under the RIP Act section 3(1).

There is little evidence to substantiate the Government’s claim that the UK will be “the best place in the world to conduct e-commerce by the 2002”. The reality is that the United Kingdom - alone amongst the G8 countries in taking unto itself an intercept capability – risks driving technology investment overseas, whilst the remaining UK industry drowns itself in endless compliance audits.Paul Motion is a partner with Ledingham Chalmers

In this issue

- President's report

- Right of citizenship underpins liberty

- This time the sky is falling

- The Human Rights Act and employment law

- New challenges, new risks?

- The new Diploma in Legal Practice

- Certification required for physical evaluation

- Act permeates all types of practice

- e-mail snooping RIP

- Challenge to legitimacy of tobacco directive