Code cracks unified regulation

Let’s remind ourselves of the background. In these columns a few months ago I spoke in uncharitable terms of the draft RIP Act “Lawful Business” Regulations which gave all the impression of having been carefully drafted over some junior minister’s lunch break. Industry lobby groups were quite rightly critical of the draft Regulations, which would for example have outlawed opening a colleague’s e-mail box when he/she was on holiday! To the credit of the DTI, however, these concerns were listened to and taken on board. A useful precedent! The finished article [Telecommunications (Lawful Business Practice) (Interception of Communications) Regulations 2000 SI 2000 No. 2699] allowed interception without employee consent in eight broad areas, including the following:-

- to establish existence of facts relevant to a business.

- to ascertain compliance with regulatory or self regulatory practices.

- ascertaining the standards achieved by persons using the systems in the course of their duties.

- determining whether a communication was relevant to the business.

It is not possible in a brief article of this nature to do more than scratch the surface of the 61 pages of the Code. Instead, I propose to focus on Part 1 Section 6 of the code, which is entitled “Employee Monitoring”.

Employee monitoring

The expression “monitoring” is but one example of the code adopting a term with no corresponding reference to be found in the Data Protection Act 1998. The Code has its genesis in Section 51(2) of the 1998 Act. This states that the Data Protection Commissioner shall arrange for the dissemination in such form as he considers appropriate of such information as it may appear expedient to give the public about good practice. Quite why it was necessary to present this information in the form of a Code is not clear. It is an unfortunate approach since, in this writer’s view, the title “Code” is likely to be persuasive with Industrial Tribunals and the EAT. These bodies are already used to taking cognisance of compliance (or not) with statutory codes. One can think for example of a corresponding provisions in Section 53 (1) (a) and 53(5) of the Disability Discrimination Act, requiring a tribunal to take account of the DDA code. If the Commissioner’s advice is also to be elevated to the status of a Code, it is therefore, all the more important that the terms should stand up to scrutiny.

The Code uses the term “monitoring” in a widespread fashion, without defining what it means. The Commissioner’s preferred starting point seems to be that monitoring will always be intrusive. But this is not the case – employers “monitoring” may range from listening to tapes of a telephone call simply to clarify the detail of a transaction, to investigating in detail an allegation of illegal use of the telephone or e-mail system. It might have been better if the Code had adopted the neutral word “access”. The Code also sets out certain standards to be expected of employers – these are “mandatory” and “discretionary” standards. The boundaries between them are not clear and it is uncertain how a “discretionary” standard will in practice be enforced in a different way from a “mandatory” one.

One of this author’s particular concerns is the advice given in relation to e-mail. Paragraph 6.3.2 of the Code suggests that employers must “provide employees with a means by which employees can expunge from the system e-mails they send or receive”. But why? Does not the employer’s right and need to undertake proper risk management procedure prevail over the employees right to eliminate without trace whichever e-mails the employee chooses? As the London Investment Bankers Association bluntly observed in its response to the consultation “this would be unacceptable even if it were technically feasible. Such a mechanism would be open to abuse and cause serious legal and regulatory risk to the firm and potentially to the market”. It is hard to disagree.Another conceptual difficulty with the code, and one which puts it squarely at odds with the approach of the Lawful Business Regulations, is its starting point that fairness of data processing has to be judged against the employee’s “right of autonomy”. It is understood that this is a turn of phrase intended to convey that the Commissioner has taken on board recent case law in this area such as the Halford case and others. However, the result is that once again employers are to have their data processing activity judged by a standard which has no basis in law – “autonomy” is not a standard found in the Data Protection Act 1998 principles. The Commissioner’s view of this difficulty is that “autonomy” is a natural adjunct of fairness, and therefore acceptable standing the need for data processing to be “fair and lawful”. Again, this author has difficulty with that proposition.

The preamble to Clause 6.3 of the draft Code states that routine monitoring of the content of all communications sent and received at work is in many cases likely to go “too far”. Once again, this appears to put the Commissioner’s approach at odds with the Lawful Business Regulations, and in particular Regulation 3(2)(c) referred to above. If “reasonable efforts” to inform employees of the possibility of interception are sufficient to confer protection upon the employer from civil or criminal action for wrongful interception; why is the same approach not adequate once data has been gathered from that activity?

Employers are right to be concerned about the present wording of the draft Code. It is to be hoped that when the revised Code is issued, more will have been done to bring its approach into line with the Lawful Business Regulations so that employers can at least begin to put in hand compliance with a unified scheme of regulation. For those interested, David Smith, Deputy Information Commissioner, will be attending a seminar in Edinburgh on 20 March at which data protection issues generally, including the Code, can be discussed. Members of the profession interested in attending should feel free to contact the writer.

Paul Motion is a partner with Ledingham Chalmers, Edinburgh. He is Convener of the Law Society of Scotland’s Electronic Commerce Committee and Scottish Legal Group chairman of E Centre UK.

In this issue

- President’s report

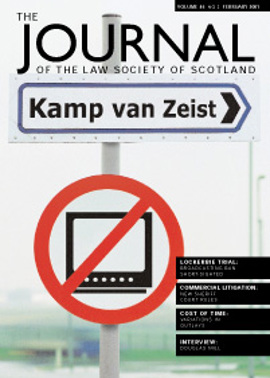

- The Lockerbie trial and article 10

- Sheriffs reclaim a role in commercial actions

- Why become a solicitor if you want to do banking?

- Promoting paralegals

- Code cracks unified regulation

- Substitute land and charge certificates

- Legal responsibilities for gas safety

- Robust self analysis the key to change

- Don’t trust your memory

- Nice Summit: the road to enlargement

- Book reviews

- Around the houses