Sheriffs reclaim a role in commercial actions

Recent Background

Under the chairmanship of Sheriff Principal Edward F. Bowen, QC., a working party was established in 1999 to consider whether the commercial court procedures of the Court of Session1 could, with benefit, be adapted to the sheriff court.

If so, should there be commercial rules for the sheriff court? The working party included representation from the Scottish business community.

In addition, by Practice Rule dated 29th July, 1999 Sheriff Principal Bowen established a separate roll for commercial actions in Glasgow Sheriff Court. Four sheriffs were nominated with specific responsibility for commercial litigation. When defences were lodged, parties were invited to a procedural hearing with a view to progressing the case. The hearing relied on the good will and voluntary attendance of the parties. Where one or more of the parties failed to attend or expressed reluctance to accede to this informal approach, the case proceeded as an Ordinary action. This was, however, rare, which perhaps speaks volumes.

It was important to realise that judicial intervention was not to be viewed as judicial interference in litigation. The purpose of the intervention was to progress the case to an early resolution whilst at the same time doing justice to the case itself.

As in the Court of Session, the hearing was intended to be businesslike as well as judicial. Gowns were not obligatory and the intention was to engender a willingness by the court to identify the matters in dispute and how they could best be resolved. Feedback was encouraged from the profession, the sheriffs and sheriff clerks.

It became apparent that the powers of the court were constrained by the Ordinary Cause Rules. The flexibility and powers of the judge of the Commercial Court of the Court of Session could usefully be adapted to commercial litigation in the sheriff court.

Radical Act of Sederunt

Consequently, with effect from 1st March 2001, the Act of Sederunt (Ordinary Cause Rules) Amendment (No.3) (Commercial Actions) 2000 inserts a new chapter (Chapter 40) into the Ordinary Cause Rules 1993 to make provision for commercial actions. There are a number of important and radical aspects to the Act of Sederunt. For example, not all sheriff courts may have a commercial procedure, there is no explicit adjustment period and the sheriff has new powers to resolve the dispute.

Whilst the new Sheriff Court Commercial Rules are similar to those of the Commercial Court of the Court of Session they have been altered for the sheriff court. The new chapter, Chapter 40, entitled “Commercial Actions”, has been inserted in to the Ordinary Cause Rules.

In terms of Rule 40.1(2)(a) a commercial action means an action “arising out of, or concerned with, any transaction or dispute of a commercial or business nature”. This definition is deliberately wide. Although there are nine specific areas (insurance, banking, partnership etc) identified in the Rule, a commercial action is not limited to those categories. Only one commercial action is excluded from the procedure, namely, consumer credit transactions.

Not all sheriff courts will have a commercial court procedure. Rule 40.1(3) states that a commercial action may be raised only in a sheriff court where the Sheriff Principal for the sheriffdom has directed that the procedure should be available. It is for the Sheriff Principal to decide if and where he wishes to adopt the commercial procedure. In making his decision, he is likely to be guided by factors such as the existing volume of commercial litigation in a particular court and the desire among local sheriffs to accept nomination to deal with commercial work in terms of Rule 40.2.

If the commercial procedure is to have credibility, there must be a fundamental understanding of the needs of the business community from the outset. This only comes from expedience of commercial litigation. Rule 40.2 states that all proceedings in a commercial action shall be brought before a sheriff of the sheriffdom nominated by the Sheriff Principal or, if he or she is not available, any other sheriff within the sheriffdom.

Although the commercial sheriff will also deal with his or her other judicial workload, the identification of specific sheriffs dealing with commercial litigation will inspire confidence in those appearing before the Commercial Court. This should achieve a consistency of approach in commercial litigation with the same sheriff dealing with the case throughout.

Commercial Procedure not obligatory

The commercial procedure is not, however, obligatory. In terms of Rule 40.4 the pursuer “may elect” to adopt the Commercial Court procedure. The pursuer does so by framing an Initial Writ as a commercial action in terms of Form G1A. The pursuer therefore has an initial discretion which is not available to any other party unless that party applies by motion under Rule 40.5 to have the action appointed to be a commercial action.

Rule 40.5 will also allow the transfer of existing commercial actions to the new procedure where appropriate.

Conversely, in terms of Rule 40.6, the sheriff may transfer a new commercial action to the Ordinary Cause procedure either on the joint motion of the parties or where detailed pleadings are required to enable justice to be done between the parties or in any other circumstances which warrant such an order being made. If a motion to appoint a commercial action to proceed as an ordinary action is refused, there must be a material change of circumstances before any further motion can be considered.

The style of the writ in a commercial action is provided in Form G1A of the Schedule to the Act of Sederunt. The pursuer is required to provide (a) information sufficient to identify the transaction or dispute from which the action arises; (b) a summary of the circumstances which have resulted in the action being raised and (c) details setting out the grounds on which the action proceeds. In the Court of Session brevity in the pleadings is encouraged. In the sheriff court the parties will also be encouraged to be succinct.

In terms of Rule 40.7 neither pleadings nor pleas-in-law are required if the only matter in dispute is the construction of a document. In commercial disputes, it could be a useful, quick and comparatively inexpensive method to obtain the opinion of the court as to the interpretation of, for example, a contract by invoking this procedure. Indeed, one can envisage situations where the financial consequences which naturally flow from a certain interpretation of a contract can be agreed. The question arises, what is the correct interpretation? Rather than raising an action for damages it would be better to agree damages in the event that the sheriff interprets the deed one way as opposed to another.

Under Rule 40.8, where a defender intends to challenge the jurisdiction of the court, state a defence or make a counterclaim, he should, as before, lodge a Notice of Intention to Defend (Form 07).

Frontloading of time and cost

After the Notice of Intention to Defend has been lodged, the defender has only seven days to lodge defences.2 A pursuer may have had many weeks or months to obtain expert reports and generally research and prepare the case. The defender could be caught unprepared by the receipt of a writ with such a short timescale for the lodging of defences.

Whilst, in practice, most commercial disputes are the subject of correspondence and communication prior to the raising of court action, the parties’ solicitors may not have been privy to this communing. In a commercial dispute of any complexity the defender’s solicitor may have difficulty preparing defences within the seven-day time limit.

Each solicitor will have to devote appropriate time and resources to prepare and plead a case within the time frame of the new rules. This necessitates an increase in the initial costs which will ultimately have to be borne by the parties. It should not increase the overall costs involved. Rather the litigation becomes frontloaded in terms of the time and costs involved. Many cases should be less expensive than the cost of a protracted litigation under the current procedure.

In terms of Rule 40.7(2) and 40.9(2) a list of the documents founded upon or incorporated in either the writ or the defences must be attached to the writ or the defences. In terms of Rule 40.13, a working bundle of documents (either chronologically or in another appropriate order) should be prepared for use of the sheriff at a hearing.

After the defences are lodged a case management conference shall be assigned not sooner than fourteen nor later than twenty eight days “after the date of expiry of the period of notice”. Consequently the pursuer will have a short period to consider the merits of the defence.

Case Management Conference

In terms of Rule 40.12(2) parties shall be prepared to provide the sheriff at the case management conference with such information as may be required to determine whether, and to what extent, further specification of the claim and defence is required. In terms of paragraph (3)(c) of the same Rule, the sheriff may allow a party to amend (as opposed to adjust) the pleadings. Whilst there are thirteen examples of orders available to the sheriff at the case management conference, these do not include provision for a period of adjustment. However, Rule 40.12(3) states that the orders available to the sheriff (in terms of Rule 40.12(2)) shall not be limited to the thirteen examples given. By implication therefore, although there is no provision for an adjustment period, it appears that the sheriff has the power to allow adjustment if this would assist the expeditious resolution of the dispute.

Rule 40.12(1) states that at the case management conference the sheriff shall seek to secure the expeditious “resolution” of the action. Contrast this with the onus on the sheriff at an Options Hearing (Rule 9.12(1)) where the sheriff seeks to secure the expeditious “progress” of the cause.

The new onus on the sheriff is to achieve a resolution “of the action”. The full stop at the end of the sentence indicates that this obligation is unqualified. The equivalent provision of the Court of Session Practice Note states “he will be proactive”3 Whilst this is not explicit in the Sheriff Court Rule, it is clearly implied.

Expeditious resolution of action

The powers given to the sheriff to achieve an expeditious resolution are sweeping. They are contained in Rules 40.12(2)-(5). For example, the sheriff may order a party to lodge reports and/or witness statements. The sheriff will almost certainly press parties to make verbal admissions on the basis of the information produced. There is provision for these admissions to be recorded in the sheriff’s interlocutor. The sheriff may order a party to lodge a statement of facts, affidavits, notes of argument, expert reports, etc.

A Record is not required unless, firstly, the sheriff orders the pursuer to make up a Record, and, secondly, the sheriff makes an order under paragraph (3) of Rule 40.12.

It is likely that the sheriff will take a businesslike view of the management of the case and press parties and their solicitors in relation to their respective positions. Solicitors must be fully briefed in relation to the strengths and, as important, the weaknesses of the case. Similarly, it is important that the solicitor considers whether to ask the sheriff to direct the other party to, for example, produce documents, elaborate upon or justify opposing averments. It is a process whereby the sheriff acting as the ultimate decision maker can now force the parties before him to focus on the issues truly in dispute at an early stage in the procedure rather than, at present, after adjustment, debate, amendment and perhaps further debate and proof.

The sheriff also has power to continue the case management conference where he considers it necessary either to allow an order to be complied with or to advance the possibility of resolution of the action.4 A continued case management conference will not be required if the disputed issues have been properly focused initially.

Where a point of law or a preliminary plea is arguable, the sheriff will almost certainly expect to be addressed on the matter at the case management conference. It remains to be seen whether the sheriff will dispose of the preliminary plea at that juncture or fix a debate. If he does fix a debate, it is likely that it may take place imminently.

In terms of Rule 40.12(3)(m) the sheriff has the power to make any order which he thinks will result in the speedy resolution of the action including the use of alternative dispute resolution. It is self evident that for the sheriff to make such an order, the case must already be in the commercial court. Presumably therefore the case has been brought because parties are unable to resolve the dispute themselves or to agree to an alternative dispute resolution procedure. It is conceivable that a pursuer may raise the case to, for example, interdict a defender or arrest assets pending the exhaustion of alternative dispute resolution procedures. If that is the case, the parties themselves may be obliged to follow the alternative dispute resolution procedure in terms of the disputed contract.

It is unlikely, however, that if the court is seized or on the motion of the issues the sheriff will unilaterally make an order for alternative dispute resolutions if this is resisted by the parties. Commercial litigation is coveted as intellectually challenging, unusual or complex. Therefore the sheriff may not wish to surrender an opportunity to deal with commercial issues which are already before the court.

Rule 40.14 allows the sheriff on his own motion or on the motion of any party, to fix a hearing for further procedure and to make such order as he thinks fit. This allows the sheriff to review matters which may have arisen between, for example, the first case conference and the second. Similarly, the parties may require guidance as to how the court wishes certain matters dealt with.

More significantly, if the case were to be sisted for a certain purpose, the sheriff may recall the sist and fix a hearing to establish what progress has been made during the period of the sist. Much will depend on how proactive the sheriff intends to be. He does not have to rely on a party bringing a motion before him.

The provisions for failure to comply with a Rule of Court or an Order of the sheriff are contained within Rule 40.15. The sheriff may refuse to extend a period for compliance with the Rules or with an Order of the Court; he may dismiss the action or the counterclaim either in whole or in part, or he may grant Decree. He may also award expenses as he thinks fit.5

Judicial involvement - an informal approach

The intention behind the commercial rules is to give the court the flexibility to resolve commercial disputes of varying complexity and value, without the straitjacket of the existing rules. The new rules allow sufficient judicial involvement to achieve this aim. 6

It often seems that experienced senior solicitors/partners refrain from attending court. Perhaps their time and earning potential are more valued in the office. In a commercial litigation of any substance this attitude may be undesirable under the new procedures. The sheriff will expect the solicitor appearing before him or her to have a detailed knowledge of the facts and circumstances at his or her fingertips. The sheriff may grant orders for the production of certain documents and if those orders are to be resisted, he will wish to know why.

The clerks will assist in the proper timetabling of cases. A computerised diary should ensure that cases are allocated to the commercial roll at a specific time.

The commercial sheriffs in Glasgow have adopted a fairly informal approach to parts of the litigation. So, for example, if a motion is not to proceed, the sheriff will allow the motion to drop on the strength of an e-mail, fax or letter and thereby avoid the necessity of the parties attending. On one occasion, a solicitor in Edinburgh conducted the hearing by conference call. On another occasion, where the value of the dispute was not high, both solicitors used the sheriff’s conference call facilities and saved the time and expense of attending court. It is this proportionate and flexible approach to litigation which will commend itself to both practitioners and clients alike.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the new rules should provide an accessible forum for commercial dispute resolution rather than having to proceed to the Court of Session for an appropriate procedure and a specialised judge. The level of commercial actions in the sheriff court might therefore increase. Secondly, there is a pre-existing level of commercial work within the sheriff court. If the streamlined procedures are shown to be more effective, this can only benefit the existing users - whether or not any further business is attracted to the court. A number of commercial actions were transferred to Glasgow Sheriff Court to take advantage of the informal commercial procedure already outlined. It is likely that commercial disputes will gravitate towards those courts having commercial sheriffs and commercial procedures.Finally, if, as seems probable, there continues to be a growth in other methods of dispute resolution, it is reasonable to suppose that that growth must have a side effect on the established forum for dispute resolution (the courts). If this is correct, the courts must learn something from the apparent attractiveness of those other methods of dispute resolution. The new procedure indicates that the courts are indeed learning the benefits of a more flexible and proportionate approach to commercial litigation.

The commercial court of the Court of Session successfully reformed its procedures so as to meet the criticisms of commercial litigants. A similar approach is now being applied to commercial litigation in the sheriff court.

A final thought. Why should such progressive thinking be confined to commercial litigation?

John McCormick has been a partner with responsibility for court matters with McSparran McCormick, Solicitors, Glasgow since 1987. In 1989 he qualified with an MBA from Strathclyde Business School and in 1999 he was the first Scottish solicitor to achieve an LLM in Advanced Litigation (with Distinction) fromThe Nottingham Law School

In this issue

- President’s report

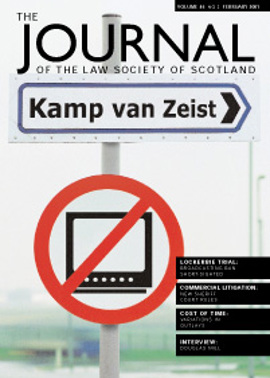

- The Lockerbie trial and article 10

- Sheriffs reclaim a role in commercial actions

- Why become a solicitor if you want to do banking?

- Promoting paralegals

- Code cracks unified regulation

- Substitute land and charge certificates

- Legal responsibilities for gas safety

- Robust self analysis the key to change

- Don’t trust your memory

- Nice Summit: the road to enlargement

- Book reviews

- Around the houses