The Lockerbie trial and article 10

“Informed of what took place substantially as if they were present” … “enabling both those within and without the walls of the court to be equally well-informed of what has taken place” … “simply an enlargement of the audience which hears them in court, but which is limited by the size of the courtroom.” The trend of the authority is clear. The media’s role, and entitlement, is, so far as possible, to bring judicial proceedings to the public.

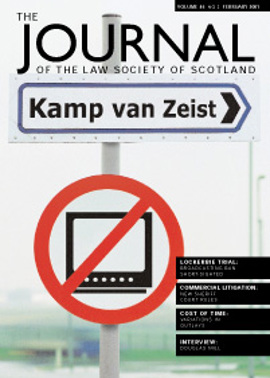

The Lockerbie trial limped on for nine months amid adjournments, secret documents and mystery witnesses. The verdicts on 31st January ended years of public and private anxiety. Some took a keen and consistent interest. But for many of us, this trial - unique for its legal, political and tragic significance – was out of sight and mind. Not even Reuters and the Press Association stationed a full-time journalist in Kamp Zeist. The endorsements of Scottish justice fall pleasantly on the chauvinistic legal ear, but reality is that most Scots will have few ways to form an opinion on the conduct of the trial in question.

Whose fault is this? Each organ allocates its resources as it sees fit. It must be borne in mind, however, that the location of the trial, its length, the unpredictability of witness appearances and adjournments all militate against full and even reportage. It did not have to be this way. The BBC petitioned twice for permission to transmit the entire trial simultaneously on the Internet, through BBC Online, and/or to transmit edited parts of the proceedings on TV and radio, and/or to compile material from the trial for post-trial documentaries. These petitions were backed by a number of other media organisations including the Scottish Media Group. They were refused in their entirety.The petitions took place prior to the Human Rights Act’s coming into force.4 Argument therefore pivoted upon whether there was truly a devolution issue which would entitle the petitioners to claim that their Article 10 rights of freedom of expression had been violated. It was ultimately held that no devolution issue had arisen. Even had it done, however, the judges would not have supported any of the media’s proposals.

The arguments make for complicated reading. Much debate centres around the consent given by the court, apparently in its administrative capacity, to the televising of the trial to “remote sites” in New York, Washington, London and Dumfries, for victims’ relatives: whether and how consent had been given, whether this was distinguishable from public broadcasting, whether the remote sites were extensions of the courtroom, etc. It is clear that the Washington and New York sites were run by the American Department of Justice, with American money, outwith both the physical and legal jurisdiction of the Scottish court. According to the Crown, “The Guidelines [agreed with the American Department of Justice] laid down rules regarding dress and decorum for those intending to view the trial proceedings at the remote sites on the basis that those sites are an extension of the Scottish courtroom. A member of the Scottish Courts Administration will be in attendance at each site.” Yet no American in attendance at Washington or New York can contract to make himself liable to the quasi-penal measures of Scottish contempt law and the only suggested sanction for breach would be for the Scottish representative to refuse admission to those who do not keep to the rules. It is straining language to call such a representative an officer of the Scottish court; the mot juste would appear to be “bouncer”. As to dress and decorum, one might as well argue that wearing cricket whites in Delhi would restore the Raj. Washington and New York are outwith the jurisdiction of the Scottish court, even as extended to Zeist; that is the legal and practical reality; and the Scottish court has no authority to delegate to its ostensible officer.

The substantive arguments against televising the trial, or any part of it, concentrated upon the presumed effect on witnesses. It was argued that some witnesses, not being compellable by the Scottish court, would not come:“… the Advocate-Depute informed me that over the past year a team of members of the Procurators-Fiscal Service has been engaged in the precognition of witnesses all over the world. … In anticipation of the hearing on the petition, the Advocate-Depute had arranged for the views of the members of that team and their foreign counterparts to be taken. The clear conclusion at which they had arrived was that, if the proceedings of the trial were to be televised, many of the witnesses simply would not attend, whether out of concern for their own safety, or because of the total loss of privacy or simply because of increased nervousness.”

No details were vouchsafed as to how this conclusion about the attitude of witnesses to televising on the Internet, as against televising to the remote sites, was reached; which and how many witnesses were involved; or whether any attempt could be made to persuade them otherwise. The media had made it clear at both hearings that the protection of witnesses’ identities by the court would be respected if televising were permitted. The assertion was made by the Crown and accepted by the court.

Next, the Advocate-Depute submitted that televising the proceedings would materially increase the risk of witnesses being briefed about the evidence of earlier witnesses: “Although it was recognised that there was nothing to prevent a witness from reading a press report or hearing a radio or television report of the evidence of a previous witness, the Advocate-Depute submitted that it would be wholly different in quality for a witness to be able to see and hear the entirety of an earlier witness’s evidence as it was given.” Thirdly, he averred there “was a risk that the evidence of witnesses might be affected in a variety of ways if the proceedings were televised. A witness might be more affected by nervousness than he would otherwise be. He might play to the gallery. He might restrict or expand his evidence in light of the knowledge that his evidence was being televised. That last consideration applied even where the evidence was only being televised for later documentary use.”A witness willing to flout the court’s restrictions might indeed be qualitatively better-prepared for cross-examination by watching the trial. This would amount to a legitimate concern under Article 10(2), which might, in principle, justify a restriction of the imparting of full information on the trial. But the correlative of that is that the other five billion people in the world, who were not Lockerbie witnesses, and who might have a legitimate interest in the trial, would also have had a far better understanding.An approach which sacrifices the full and proper and timeous provision of pertinent information to the world on the spiralling hypotheses that (a) a witness would do this, (b) would thereby find out something to his advantage, which he could not have found out by sending someone into the court, or reading the newspapers and (c) would be able to use that incremental information so as to defeat Counsel in a forensic contest, shows no regard for proportionality. Indeed, its logic - that more is less in the matter of full and fair reports - is bewildering in the light of the dicta from English and Scottish judges quoted above. Either the media is enjoined and permitted to inform the public to the same extent as though the latter were in the courtroom, or it cannot. There cannot be open justice without the possibility of witness briefing. One has to balance the likely costs of one against the likely benefits of the other.

That live broadcasting of the full proceedings would have been the next best thing, for that percentage of the world’s population which could not be in Zeist, is beyond rational doubt. It would be, as Lord Macfadyen observed, ”The most effective, complete and detailed way for [petitioners] to report the proceedings of the trial … ” To place a questionable hypothesis affecting the few, over a self-evident certainty affecting the many, is to give no perceptible weight to the Article 10 value at all.

As regards the effect upon witness behaviour, here a plea to the relevancy is in order. Witnesses may well be nervous giving evidence in a mass-murder trial ten years after the event, under the eye of several governments and the families of the victims. Whether the knowledge that their televised image is being carried to the world beyond London, New York, Washington and Dumfries would exacerbate their nervousness - or, conversely, any tendency to self-aggrandisement - is also questionable, but allow it for the moment. The issue is whether, under examination, cross-examination, and re-examination, they will tell the truth. Their curtailing or elaboration of their evidence is a matter for the skill of Counsel. The notion that decreased nervousness would increase a witness’s propensity to disclose the truth borders on the perverse, given that courts are deliberately imposing places; one rarely finds macers, grey wigs or coats of arms in, for example, an aromatherapy clinic.

A further argument advanced, and apparently accepted, was that the accused would not consent to the public broadcasting of the trial: “Both accused came to The Netherlands voluntarily to stand trial and that was on the basis that Scots law and practice would be applied … It would clearly be prejudicial to the accused if their images were to be televised world-wide in the context of the allegations made against them and there were legitimate concerns about the effect which public television would have on a fair trial. The accused were not prepared to agree to a documentary programme being televised after the trial was over.”

The Lord President’s Guidelines of 1992, covering the conditions upon which it was felt appropriate to have television in the courts, give this veto to all the principal players in court proceedings, a fact which explains the paucity of such television programmes over the past eight years. The Lockerbie trial shows the high-point of futility in giving such a veto to the accused. (The fact that the accused were able, without irony, to present their standing trial as some sort of sporting gesture, illustrates quite what a peculiar animal the Lockerbie trial was, and why it more than warranted watching.) Images of the accused have been shown world-wide for almost a decade; if the court accepted that that was prejudicial, then in good faith, the trial ought to have stopped altogether.

Most startling in the accused’s reaction, however - even making allowances for the self-absorption of two men facing such serious charges - is the refusal to countenance a documentary: “If they were acquitted, they [do not want to] have to endure re-runs of the trial and the risk of undergoing a subsequent trial by the media.”

Here “trial by media” is plainly used as a synonym for “discussion”. The media cannot imprison anyone. If a living individual is defamed, he has a civil remedy, where, once again, he will have the privilege of being presumed innocent. The accused cannot, under Scots law, be re-tried. What they were really saying here, is that they did not want such a

documentary to take place in the event of their acquittal - an acquittal which would have left the allocation of blame for the crash unresolved for the relatives and friends of the 270 victims - because they did not want any more talk. Even domestic contempt law within the United Kingdom, foul as it has fallen of the European Court of Human Rights on occasions5 has never sought to curtail public discussion of a trial after the verdict. Does this correspond to the sort of pressing social necessity which Strasbourg has made it clear is required to justify a restriction under Article 10(2)? This was supposedly a public trial, paid for by the Scottish public, but one which - owing to the restrictions which the accused placed upon such access by insisting on being tried outside of Scotland - the public have a very limited practical ability to observe.

The Scottish court itself, in a petition by the accused against Times Newspapers Limited,6 refused to find the Sunday Times guilty of contempt on the basis that their article and editorial would create a perception in the minds of the accused that they were not receiving a fair trial. As the Lord Justice-Clerk put it, “I do not think that liability for contempt of court should depend on the viewpoint of the party to the proceedings … It is one thing to say that it is good law that a party to proceedings should be able to rely on their being no usurpation by any other person of the function of the court … It is quite another thing to say that what is contempt of court should be judged by reference to the perspective of that party.”

It is unclear why, then, they should be able to dictate the mode of coverage used by the media.

Lord Caplan observed in the same case: “The questions of pre-judging the trial and ‘trial by media’ are really the same point … If the public were inclined to form any views about the quality of British justice from this trial it is more likely to be influenced by the manner in which the trial itself is conducted.”

And that is the crux of the matter. The public was not in a position to form a view about the quality of Scottish justice from this trial because it was not represented at the trial, except through the fleeting visits of itinerant journalists. Those regularly in the courtroom at Zeist had a special interest in the trial. Those at the remote sites, although they hold all our sympathy and good wishes, were not representatives of the public, but of a particular concern.

The journalist who sought to cover the Lockerbie trial the way he would cover a domestically-held trial of equivalent public significance (if there has ever been one) was subject, however unintentionally, to economic sanctions.

The media will always find other stories to chase, many, in tabloid terms, more sensational than Lockerbie. The loss is to the intelligent public, and to the court’s ability to vindicate its manner of dealing with this highly controversial, bespoke trial.

In rejection of the BBC’s offer to give the public information about the trial “substantially as if they were present” - the traditional desideratum of open justice - an opportunity was missed which is not likely to come again. The average trial will be inappropriate for television for a variety of reasons. This opportunity was missed because of unsubstantiated suggestions about the effect upon witnesses, and the preferences of the accused.

Subsequent to the petitions, the court also refused administratively a request by the BBC to televise the closing submissions in the trial, which obviously would not feature any witnesses and need not even feature the accused. The roots of an aversion to television on that scale are not solely rational. The resistance to scrutiny by lawyers, as well as others, comes, it is submitted, primarily from the gut. Lord Clyde observed7 that the Act of the Scottish Parliament in 1693, requiring the judges to discuss their decisions in public, was “a course which did not commend itself to Lord Stair.” Legal squeamishness in these matters is nothing new. That does not make it right.

The argument before Lord Macfadyen that “what was sought by the petitioners was wholly novel. It had never been done or sought in Scotland before. It was not permitted in England or elsewhere in Europe.” is as cool a trotting out of the ad antiquam fallacy as may be heard. A reluctance to experiment where stakes are high is legitimate. A refusal to examine what the stakes really are, is not. No-one thought of television, after all, until a Scot did. It still works.

Rosalind McInnes is a solicitor with BBC Scotland

In this issue

- President’s report

- The Lockerbie trial and article 10

- Sheriffs reclaim a role in commercial actions

- Why become a solicitor if you want to do banking?

- Promoting paralegals

- Code cracks unified regulation

- Substitute land and charge certificates

- Legal responsibilities for gas safety

- Robust self analysis the key to change

- Don’t trust your memory

- Nice Summit: the road to enlargement

- Book reviews

- Around the houses