Disclosure: divorce lawyers and proceeds of crime

The recent decision of Dame Butler-Sloss in P v P has confirmed for many solicitors that the terms of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (“the Act”) go far beyond the more familiar money laundering checks and the various duties which previously had to be fulfilled. In the judgment of 8 October 2003, the English High Court held that a solicitor who knows of or suspects involvement in an arrangement which facilitated the acquisition or use of criminal property must make an authorised disclosure to NCIS and seek consent.

The court was considering an ancillary relief application by a wife. Her advisers were concerned about their duties under the 2002 Act and considered that money laundering issues might arise from the information they had obtained about the husband’s financial affairs. Section 328 of the Act provides that it is an offence where a person “enters into or becomes concerned in an arrangement which he knows or suspects facilitates… the acquisition, retention, use or control of criminal property by or on behalf of another person.” Property is defined as “criminal property” if “(a) it constitutes a person’s benefit from criminal conduct or it represents such a benefit (in whole or part and whether directly or indirectly) and (b) the alleged offender knows or suspects that it constitutes or represents such a benefit”.

Accordingly under section 328 the solicitors who were negotiating a financial outcome for their client (“an arrangement”) and had suspicions that the settlement might include assets which were criminal property or derived from such property had to make a report.

Affecting client trust

The implications for family solicitors are enormous. Even a minor tax evasion disclosed to solicitors in the course of enquiries with the usual financial information needed to advise a client properly will result in an obligation to make an authorised disclosure. There is no lower financial limit. There is no de minimis rule. The level set for money laundering does not apply here. It has to be remembered that section 328 relates to criminal property (or the benefit from any criminal act). Solicitors cannot turn a blind eye to such information. If they do they commit an offence punishable by up to 14 years’ imprisonment. There is no defence of client confidentiality to such a charge. It had been thought that legal advisers obtaining such information in the course of legal proceedings would have privilege, but in her ruling Dame Butler-Sloss held that there was no legal privilege exemption for matters arising under section 328.

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of this case. Solicitors will have to err on the side of caution and report even the most minor criminal activity about which they have become aware or have suspicions. Most likely this will relate to tax evasion or benefit fraud. That will inevitably affect the degree of trust which exists between solicitor and client. If clients were to become aware of the reporting obligations on their agents, it would not be surprising if there was a tendency not to disclose certain or all information which would normally be required. Even the vaguest suspicion may make a solicitor hesitate in asking a question which should properly be asked of a client, simply because the solicitor does not want to know the answer due to the reporting obligations which flow from that knowledge. Inevitably, there will be cases where a spouse who is not satisfied with the likely level of settlement uses the threat of a report to NCIS to extract a better financial settlement.

While the decision relates to a family case, it is clear that it can apply equally to other areas of law. Those involved in corporate matters and business acquisitions might very well face the same sort of problems if they become aware of or suspect any (even minor) improper activity in circumstances where they are negotiating arrangements for (say) the sale of a business. NCIS are likely to be faced with a large number of reports probably very few of which will involve the serious crime which the Proceeds of Crime Act was intended to uncover.

Negotiating is “being concerned”

Solicitors need to realise that separate rules (under section 330) apply to suspicions about money laundering specifically. They need to make themselves and their staff aware of the obligations they now have. It is important that all solicitors realise that there are distinct reporting obligations under section 328 relating to arrangements involving any criminal property, with no lower limit on value. In these solicitors might be “concerned in” the arrangement by the simple fact of negotiating the arrangement itself. The offence is committed if no disclosure is made. Separately, concerning the more familiar money laundering rules, the offence is failure to disclose following knowledge or suspicion of money laundering.

Solicitors have also been very concerned that tipping off, an offence under section 333, might be committed if the client is told of a disclosure made. In the decision in P v P Dame Butler-Sloss suggested that the legal profession protection applies so that disclosure made in connection with the giving of advice to a client is not treated as an offence provided it is not done in furtherance of criminal activity. It should be noted however that the privilege does not mean that the solicitor does not need to report the offence discovered to NCIS in the first place – simply that subsequently telling the client or others (for example the solicitor on the other side of a transaction) will not necessarily constitute the offence of tipping off. If there is a belief that the disclosure has been made to a client with an improper purpose the legal professional exemption will be lost. The judgment did confirm however that unless the requisite improper intention is there, the solicitor should be free to communicate such information to the client or opponent as is necessary and appropriate in connection with giving legal advice or acting in connection with actual or contemplated legal proceedings. Solicitors must tread carefully.

The Act imposes an enormous burden on solicitors particularly for those who are faced with the possibility about making a disclosure about their own client. There is potential for delay in proceedings while solicitors consider their own position. The decision sets out good practice and the court’s view on the NCIS position statement, although in part the court felt that this needed amendment. Those involved in civil litigation and family practitioners in particular need to become familiar with their duties and obligations under the Act without delay.

Janice Jones is a partner in Harper Macleod, Glasgow, specialising in family law

In this issue

- Big wheels keep on turning

- Outsourcing: trick or treat?

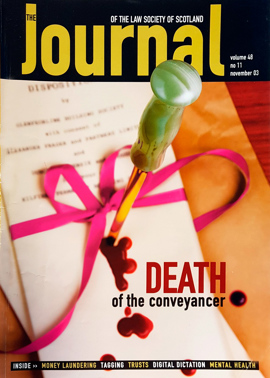

- The end of conveyancing as we know it

- A conflict of interest

- You’re tagged

- The beginning of the end

- The Scottish Law Commission’s Trust Law Review

- Disclosure: divorce lawyers and proceeds of crime

- Talking digital

- Keep an eye on your fee-earners

- Dot.com survivor!

- Determining place of payment

- Mental Health Act: care and treatment

- Affidavits in undefended divorces

- Scottish Solicitors’ Discipline Tribunal

- Jury trials in the Court of Session

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Preserving superiors’ rights

- Housing Improvement Task Force

- Land certificates: could this be yours?