Keep an eye on your fee-earners

The report of a recent Discipline Tribunal decision refers to “failure to supervise [an employee] to a standard to be expected of a competent and reputable solicitor”.

The proceedings at the Tribunal evidently included deliberations on the adequacy of the “system of supervision” in operation in the solicitor’s practice.

Quite apart from the possibility of a finding of professional misconduct, there is no doubt that shortcomings in supervision arrangements have the potential to result in service complaints and in claims against the practice.

Delegate, but supervise

What are the elements of effective supervision?

- Supervise proactively – don’t wait for colleagues to come to you with problems

- See outgoing and incoming mail, including faxes and emails

- Insist on case review meetings

- Encourage discussion and give feedback

- Avoid cutting discussions short

- Review colleagues’ progress regularly

- Assess training needs of qualified and unqualified colleagues.

Some solicitors pride themselves (in many cases, justifiably) on their relaxed working environments, which encourage a sense of responsibility and worth from fee-earners. However, such working practices must not become an excuse for failure to supervise fee-earners. The scenario where a fee-earner is left on their own in an office or department is a common one. In some practices, this is unavoidable – however, care needs to be taken that the fee-earner does not feel out of their depth – either fielding urgent calls from clients or supervising support staff.

Is lack of effective supervision a “cause” of claims?

If not a “cause” of claims, then lack of effective supervision is at the very least a contributory factor in some claims.

Case study 1: time bar

Following the departure of an assistant, his files are redistributed between two other assistants. Some days later, one of the assistants advises you that she has come across several personal injury files that appear to be time barred. How could this situation have been prevented?

If this sort of situation arose, one would want to establish precisely what had gone wrong, what was the cause of the problem and whether there were any contributory factors. Without these facts, preventive action may be ineffective.

In time barred personal injury files, one strongly suspects that lack of, or ineffective, supervision must have been a factor. As well as other systems and procedures, the following arrangements for supervision of assistants’ work would appear to be appropriate:

- Case review meetings

- Physical file reviews

- File audits

- A system to monitor workload to check adequate resources/ management/ handling of cases

- Training sessions on understanding time bar periods particularly for unusual types of claim/circumstances.

There have been instances of errors and omissions on the part of senior, experienced solicitors with an entirely satisfactory track record of being largely self-sufficient, either as a result of a mental block or blind spot or due to stress or other personal problems. An effective system of supervision should have as one of its aims the earliest possible detection of such problems occurring.

Case study 2: title

One of the commercial property case studies (case study 2) in the October issue of this column also illustrates how lack of or ineffective supervision can lead to client dissatisfaction and claims.

An assistant was part of a team assigned to the acquisition of a development site for a client. The work had been won on a tender. Conscious of the slim margins, the partner delegated all of the work to his associate. The associate was completely snowed under with work and he, in turn, delegated the bulk of this project to the assistant. The assistant failed to note title properly, overlooking the fact that the client had no right of access to the site. This was never picked up by the associate or by the partner.

What was the cause of the omission?

Failure to check all relevant deeds? Failure to appreciate the meaning of title provisions? Failure to clarify instructions?

What were the contributory factors?

The assistant’s lack of experience or poor technical knowledge? Poor delegation? Inadequate supervision and checking? Poor management of workloads?

All of these factors could and should be addressed by an effective system of supervision.

How effectively are you supervising?

Questions to ask yourself:

Is this your practice?

“All incoming and outgoing mail (including faxes and emails) is seen by a partner”

“The partners know how much work everyone is handling”

“All files handled by assistants are reviewed to ensure that they are being managed properly”

“No one would be made to feel incompetent if they needed to speak to a partner about a problem”

“We have regular meetings to share ideas and to discuss areas of risk”

Am I really contactable when out of the office?

Saying it loud and often doesn’t make it true. Merely saying to a fee-earner that you’ve got your mobile is little comfort if they know it will be switched off all day as you are in court

Do I really have an open door policy?

The phrase “open-door policy” is one of the most misused and empty sayings in the whole pantheon of practice management – principally because it is just that: a phrase, often with no actual commitment behind it. Fee-earners will be reluctant to discuss matters if you are constantly waving them away as you need to catch up on urgent emails/telephone clients or if they are given an audience prefaced with the words “make it quick, then”.

If you don’t have the time to discuss things immediately, schedule an alternative slot straight away and advise the fee-earner/member of staff.

Keep to that slot – you wouldn’t brush off a client meeting, so don’t have a different attitude towards staff meetings.

If an open door isn’t really possible, admit it to yourself and others but come up with an alternative – a set time every day when you will definitely be available for internal meetings and discussions.

How well am I communicating with my staff (and vice versa)?

How approachable you think you are may be some way removed from other individuals’ perceptions – take time to find out what others think of your working practices.

Don’t wait for staff to come to you with fully developed problems – you should be in a position to intervene before it’s too late.

Don’t adopt a critical/irritated attitude when dealing with problems – do it once and you are having a bad day. Do it twice and you will always have a reputation as being unapproachable and possessing a short fuse – a sure-fire way of having staff hide problems from you.

Do I expect a junior employee to be able to manage support staff in the office?

Is this a fair expectation in addition to them coping with the legal work which has been given to them?

Is that individual comfortable with perhaps being the most senior person in the office in my absence?

Have you told support staff that you are the person to ask if there are particular decisions to be made?

Supervision should be an important part of risk management procedures – done well (and this does not necessarily mean being heavy-handed), it will minimise the chances of a complaint or claim. In addition, proper supervision means effective training, which must be beneficial to both supervisor and supervised.

In this issue

- Big wheels keep on turning

- Outsourcing: trick or treat?

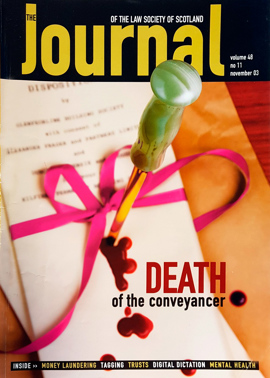

- The end of conveyancing as we know it

- A conflict of interest

- You’re tagged

- The beginning of the end

- The Scottish Law Commission’s Trust Law Review

- Disclosure: divorce lawyers and proceeds of crime

- Talking digital

- Keep an eye on your fee-earners

- Dot.com survivor!

- Determining place of payment

- Mental Health Act: care and treatment

- Affidavits in undefended divorces

- Scottish Solicitors’ Discipline Tribunal

- Jury trials in the Court of Session

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Preserving superiors’ rights

- Housing Improvement Task Force

- Land certificates: could this be yours?