Mental Health Act: care and treatment

The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Bill was introduced to the Scottish Parliament on 16 September 2002. The passage of the Bill marks the first major overhaul of mental health law for 40 years, and together with the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act, the Bill demonstrates the commitment of the Scottish Parliament to deal with mental health law and the relative services in Scotland.

During the final debate on the Bill, the Minister for Health and Community Care, Malcolm Chisholm, identified the major reforms which the Bill will introduce. These include:-

Principles that must be considered

The Act sets out a coherent set of principles which must be considered by people and organisations with responsibilities under the Act. This principled approach was recommended by the Millan Committee, which prepared the groundwork for the Act, and ensures that concepts such as reciprocity, non-discrimination and respect for carers are at the heart of this legislation.

The Mental Health Tribunal

Under the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984 (“1984 Act”) a sheriff sitting alone decides applications for detention. Part 3 of the new Act establishes a new Mental Health Tribunal which will act as a judicial body, authorising compulsory treatment orders (CTOs), and dealing with appeals against and reviews of CTOs, short-term detention, compulsion orders and other mental health disposals affecting mentally disordered offenders.

The tribunal will have three members consisting of a legally qualified chairperson, together with a medical member and a member with professional and/or personal experience of mental health services. The legal member must be an experienced solicitor or advocate or perhaps an academic lawyer with appropriate expertise. The medical member will normally be a consultant psychiatrist or recently retired consultant psychiatrist. The third member will have a background in nursing, social work, or another relevant profession such as occupational therapy, or have personal experience as a career or user of mental health services. Members will be appointed by Scottish Ministers and will require appropriate training in mental health practice and mental health law. The tribunal forum will provide a multi-disciplinary setting which allows for a full discussion of the best options for the patient.

Compulsory treatment orders

Perhaps the most controversial reform in the Act is the introduction of a new compulsory treatment order (“CTO”) which will allow care and treatment to be tailored to the personal needs of each patient, whether in hospital or in the community. Non-hospital based compulsory long-term care is currently provided for under the 1984 Act, where “leave of absence” entitles psychiatrists to discharge compelled patients from hospital for weeks or months at a time if satisfied that the patient is well enough. However, the patient is not formally discharged from long-term compulsion and may be compelled to return to hospital if the order is still in force and the patient’s mental health deteriorates. The difference under the new Act is that it will be possible for the tribunal to authorise a CTO that is entirely based outside a hospital setting – a community based compulsory treatment order.

Duties on local authorities

The new Act will place duties on local authorities to promote the wellbeing and social development of all persons in their area who have, or have had a mental disorder. This builds on the duties in the 1984 Act to provide aftercare, training and occupation.

Advocacy to be available for all

The Act also introduces new provisions to ensure that advocacy is available for everyone with a mental disorder. Advocacy in this context differs from traditional courtroom advocacy. It is intended that advocacy will allow people to make informed choices about, and to remain in control of, their own health care. The Millan Report noted that this is “helpful for people who are at risk of being mistreated or ignored, or who wish to negotiate a change in their care, or are facing a period of crisis”.

Broader patient representation

The Bill introduces more freedom for patients to choose who represents their interests. The Bill provides for the nomination of a “named person”, with similar legal rights to those which the 1984 Act gives the patient’s “nearest relative”. The main difference between a named person under the Bill and a nearest relative under the 1984 Act is that a nearest relative is an automatic appointment whereas a named person can be chosen by the patient. This change seeks to address the risk of challenge under the European Convention on Human Rights. In a case brought under the Convention (JT v United Kingdom (1998), Application No 26494/95), the fact that the applicant was not able to change her nearest relative, despite having good grounds to do so under the English Mental Health Act 1983, was ruled in breach of article 8 of the Convention. The current law has therefore been criticised for denying people choice, and as leading to a wholly inappropriate person being the nearest relative.

Conditions of excessive security

The Act enshrines in statute the right to appeal against conditions of excessive security. The current law has resulted in a number of patients being detained in the high security State Hospital at Carstairs in circumstances where a medium secure unit would be more appropriate. Parliament recognised that medium secure units must be developed as soon as possible to embrace the principle of the least restrictive approach which underpins the Bill.

The work of the Law Society of Scotland (“the Society”), the Mental Welfare Commission and numerous other voluntary organisations was recognised during the final debate on the Bill. In particular, Mary Scanlon MSP noted that “the Parliament owed a debt of gratitude to the Law Society, the Mental Welfare Commission and the Scottish Association for Mental Health”. She added: “the responsibility for scrutinising the legislation fell to them, because I had to assume that, if they raised no concerns, it was was OK to agree to certain points”. In conjunction with the Mental Welfare Commission, the Society submitted numerous amendments to the Bill at stage 2. Although many of these were not formally passed, the Executive did give assurances that they would either consult further on the points raised in the amendments, address them in the Code of Practice or, indeed, lodge their own amendments at stage 3 to address the concerns identified in the Society and Mental Welfare Commission amendments. This was indeed the case and many of the amendments suggested by the Society and the Commission were lodged by the Executive after further consultation with interest groups, and passed at stage 3.

The Bill was welcomed by MSPs at its final stage of consideration and the Parliament agreed that the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Bill be passed but, in doing so, supported the view expressed by many giving evidence on the Bill, and by the three committees of the Parliament, that the aims of the Bill will not be met unless facilities are adequate to meet demands.

The Health and Community Care Minister announced on 20 March 2003 that the preliminary date for the commencement of the Bill’s main provisions was October 2004. He added that some free-standing provisions, such as the amendment to the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984 to allow for the appointment of a new Chief Officer to the Mental Welfare Commission, will be brought into operation as soon as possible. He also stated that the Government intended to appoint a President of the tribunal to oversee the latter stages of preparatory work by the end of the year and to issue a draft code of practice.

In the meantime, the Scottish Executive has set up a Mental Health Law Implementation Team to prepare for the new Act. The team is working with a range of interested parties to develop a coherent strategy for monitoring, assessing and researching the operation of the Act and has published a consultation paper on this research programme. It is intended that the full research programme will be published after the consultation process is complete and the responses have been analysed. The aims of the research programme are to:

- provide information to support the implementation of the Act;

- contribute baseline information to build understanding of the operation of the 1984 Act;

- evaluate the operation and impact of the new Act;

- evaluate whether the aims of introducing the new Act have been achieved, taking account of the expectations of all stakeholders.

The research programme will continue until 2008, by which time the new Act will have been implemented, had the opportunity to bed down, and been evaluated.

In this issue

- Big wheels keep on turning

- Outsourcing: trick or treat?

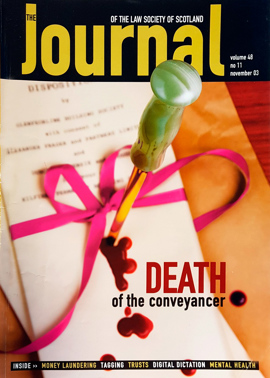

- The end of conveyancing as we know it

- A conflict of interest

- You’re tagged

- The beginning of the end

- The Scottish Law Commission’s Trust Law Review

- Disclosure: divorce lawyers and proceeds of crime

- Talking digital

- Keep an eye on your fee-earners

- Dot.com survivor!

- Determining place of payment

- Mental Health Act: care and treatment

- Affidavits in undefended divorces

- Scottish Solicitors’ Discipline Tribunal

- Jury trials in the Court of Session

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Preserving superiors’ rights

- Housing Improvement Task Force

- Land certificates: could this be yours?