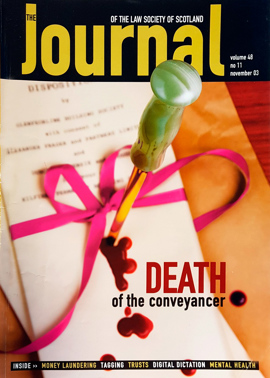

The end of conveyancing as we know it

It was odd one morning to wake up to the realisation that I was the only law professor holding a chair of conveyancing at one of the Scottish universities. This solitary situation occurred following the retiral of John Sinclair as Professor of Conveyancing at Strathclyde University. That of course is not to say that conveyancing is untaught in other universities. However the professors and others who teach that subject are not professors of conveyancing; they are, by and large, professors of, or lecturers in, property law and indeed it is difficult now to distinguish between pure property law and the law and practice of conveyancing. Nor, frankly, is it safe for a solicitor to do so.

On 28 November 2004 two (and probably three) Acts of the Scottish Parliament will come into force:

- The Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc (Scotland) Act 2000;

- The Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003; and (presumably)

- The Tenements (Scotland) Act 2004.

While many would say that these measures represent the greatest upheaval in conveyancing practice for centuries, they are, in reality, reforms of pure property law as opposed to technical reforms of conveyancing practice and procedure.

In 1985 in the preface to the first edition of Halliday’s Conveyancing Law and Practice, the late professor stated in relation to his own treatment of the subject that: “Substantive law is touched upon only in so far as directly related to the adjective law of conveyancing, and even within that field the increase in specialism introduced by modern statutes and developed in practice in particular types of transaction renders it impossible to treat many topics adequately within the compass of a general textbook.”

In the introductory chapter of volume I of the same work Professor Halliday defined conveyancing as: “that branch of the law which deals with the preparation of deeds. It is the body of law and procedure which relates to the constitution, transfer and discharge by written documents of rights and obligations in connection with property of all kinds both moveable and heritable”.

I wonder whether after 28 November 2004 there will really be much law which relates to the practice and procedure of conveyancing as such, if one regards conveyancing, as Professor Halliday did, as the law which relates to deeds and other writings. Other factors such as the development of the land registration system also impact on conveyancing as we have come to understand it.

The end of feudalism

Conveyancing technicalities were very much bound up with the feudal system. Originally a vassal could hardly move, marry or even die without some sort of charter from the superior. Over the centuries of course feudal conveyancing has been simplified and the advent of land registration in 1979 has further simplified the deeds which transfer heritable property. The feudal system relied on the odd concept of separate estates in the same land with the Crown holding a paramount superiority. On 28 November 2004 the whole system will collapse in on itself from the Crown downwards, leaving the proprietor of the dominium utile as the holder of an estate of simple, or if you like absolute ownership. Accordingly all feudal conveyancing forms and deeds will cease to be relevant overnight.

Land registration

Land registration has been creeping, slowly but surely, across Scotland since 1979. The Scottish Law Commission are currently looking at the Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979 with a view to reform. Under land registration it can be argued that ownership is not created or transferred by the disposition but by the act of registration itself. The real right is created on the making up of the title sheet. Even the land certificate is merely evidence of what is on the title sheet. There are no title deeds as such in a land registration system. With the dismantling of the feudal structure and the spread of land registration, conveyancing procedures become less formal.

Title conditions

The principles of the existing law relating to real burdens have required an almost impossible standard of precision for the creation of a real burden binding on a singular successor. After the coming into effect of the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 real burdens will however no longer be subject to such strict rules, nor to a contra proferentem construction (see sections 2(5) and 14 of the 2003 Act). The spirit of the burden may be more important than the letter. These sections are likely to be retrospective in effect (section 119(10)). Here again the strict rules of conveyancing are making way for the more principled and flexible rules of property law.

ARTL – the end of deeds?

The land registration systems of many countries are now automated. In such systems the title sheet is held in the register but can be accessed electronically. Moreover the content of the title sheet can, subject to safeguards, be altered electronically each time a property changes hands. In Scotland the Keeper has, for some time, been developing a system of automated registration of title to land for Scotland. Many firms have participated in a pilot scheme where an electronic transaction has run concurrently with the normal paper transaction. As the law stands at the moment, writing is required for the transfer of an interest in land (Requirements of Writing (Scotland) Act 1995, section 1(2)(b)). What is clear is that the law will be changed, possibly even by delegated legislation, to allow property to be transferred by electronic means. There may still be deeds as such but they will be digitally created and digitally signed. Eventually this system may develop to a point where there is no need for any deed at all. It will simply be a matter of entering and processing data. The name of the seller will be deleted and the name of the purchaser inserted, and the security granted by the seller replaced in the charges section by the security granted by the purchaser. There is no doubt that the importance of the written word is diminishing fast.

The balance of the transaction

When I qualified as a solicitor in 1969 there is no doubt that the bulk of the work in a conveyancing transaction related to the title. The conclusion of the missives was simply a necessary preliminary to the conveyancing. Time was taken up examining and noting title and preparing draft after draft of the disposition and the loan documents. Matters have now changed to the point where the conclusion of missives is perhaps the most important and complex part of the transaction. The actual conveyancing and the registration of the title have become almost mechanical exercises. Missives are regulated by the law of contract and not by any law or practice of conveyancing. So far as problems arise in an ordinary transaction they very often arise in relation to the obligations undertaken by the parties in the missives. That is not to say that title problems do not themselves arise. However in my experience, and in the experience of other professors who give opinions, the problems which arise in relation to title are essentially property law questions as opposed to purely conveyancing questions. I have only given a handful of opinions in relation to the execution of deeds. I have given literally hundreds of opinions in relation to servitudes and the interpretation of missives.

Practice groupings in firms

In the late 1960s and early 1970s legal firms, even large city legal firms, tended to have only two or possibly three departments. Most firms had a court department and a conveyancing department. It is, I think, significant that most firms nowadays have a property department and some have separate property departments for commercial and private client work. There are in addition many other discrete departments. Some firms have a private client department but few firms have a conveyancing department so called. This is a commercial realisation of how the law has actually developed over the years and these developments in practice mirror in many ways the way in which conveyancing and property law is taught at universities. In the current session conveyancing in Glasgow University is being taught as part of a larger property law course and emphasis will be on the legal principles involved rather than the formalities. Conveyancing is being taught in context. I don’t think that the conveyancing partners of the late 1960s would recognise their modern property law fee earners – more involved in the negotiation and conclusion of missives than in the actual transfer of the title.

The legislation

The new legislation focuses on property law. There is more emphasis on the content of a real burden and the identity of the person or persons who may enforce it than on the words used to create it. Moreover new types of burden enforceable only by public or quasi-public authorities such as conservation bodies have appeared. Essentially these new personal burdens are statutory creations. The law of the tenement which has so long been regulated by an archaic set of rules backed up and usually amended by the titles to property will soon be found in a statutory backup code which sets out a sensible scheme for the management of the property, as opposed to a raft of real burdens all to be interpreted in the strictest manner possible.

The future

The late Professor Halliday was wont to describe himself as a mere conveyancer, but of course he was much more than that; he was an excellent lawyer as well as a highly respected professor. His knowledge of the law extended well beyond the strict confines of conveyancing procedure and practice. In the past solicitors who practised in property law have expended a great deal of effort defending the so-called conveyancing monopoly. The licensed conveyancer experiment in Scotland failed and the Scottish Conveyancing and Executry Services Board is being wound up. Property lawyers have cast aside the old defensive posture and have developed well beyond the narrow confines of pure conveyancing practice. I am confident that they will be able to meet the challenges ahead as lawyers and not mere conveyancers.

Robert Rennie is Professor of Conveyancing in the University of Glasgow and a partner at Harper Macleod, Solicitors, Glasgow

In this issue

- Big wheels keep on turning

- Outsourcing: trick or treat?

- The end of conveyancing as we know it

- A conflict of interest

- You’re tagged

- The beginning of the end

- The Scottish Law Commission’s Trust Law Review

- Disclosure: divorce lawyers and proceeds of crime

- Talking digital

- Keep an eye on your fee-earners

- Dot.com survivor!

- Determining place of payment

- Mental Health Act: care and treatment

- Affidavits in undefended divorces

- Scottish Solicitors’ Discipline Tribunal

- Jury trials in the Court of Session

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Preserving superiors’ rights

- Housing Improvement Task Force

- Land certificates: could this be yours?