Football’s financial red card

With the satellite television revolution of the 1990s, money poured into the game of football in the UK at exorbitant levels. The spending of clubs both in Scotland and in England reflected this newfound wealth. To some extent, in England’s Premiership (“FAPL”) spending has continued with successive television deals increasing in value (although it should be noted that the latest deal recently negotiated between the FAPL and BskyB, is under scrutiny from the EC Competition Commission and is likely to be found to be anti-competitive). In Scotland and the lower divisions of England, spending has been curtailed. There have been a number of well-publicised financial difficulties encountered by sizable and well known football clubs.

Notwithstanding the Premiership’s wealth, Leeds FC is facing administration. Chelsea FC, before being bought by Roman Abramonvich, had debt in excess of £100 million and was reportedly close to taking protective measures. When ITV Digital collapsed, a number of Nationwide Division 1 English football clubs were placed into administration. In Scotland, Motherwell FC has been under the management of an interim administrator for over 18 months and is only recently beginning to show signs of coming out of administration. Most recently, Dundee FC called in administrators when a crippling financial policy, with an overspend of £100,000 per week, saw debts rise to an unbearable level of around £20 million.

The law governing insolvency for businesses both north and south of the border is largely the same, emanating from the Insolvency Act 1986. The rules that supplement the Act differ in Scotland and England but are largely the same. In the context of the business of football, these laws and rules of procedure are only part of the picture. Football clubs contemplating administration must also consider the relevant sporting consequences of such steps.

Each club in membership of a league in Scotland and England must abide by the articles of their football association, being the Scottish Football Association (“SFA”) and Football Association (“FA”) respectively. Also, rules governing the membership of particular leagues exist and must be observed. Both the Scottish Premier League (“SPL”) and the FAPL have rules of membership.

The rules of the SFA dictate that if a club becomes unable to pay its debts or has liabilities in excess of its assets, the club’s membership of the association may be suspended or terminated. The rules of the SPL contain a similar provision. Fiscal policy has also been given prominence in the SFA National Licensing Procedures. Shortly to be a mandatory requirement, each club will have to satisfy various criteria, including that it is solvent and can trade for the full season, to obtain a licence. If a club does not have a licence, it will not be permitted to play any fixtures.

In England, the position is similar in the divisions below FAPL, whereby the Football League, which administrates the divisions, has approved new regulations forming an “Insolvency Policy” commencing in season 2004-05. In this policy, sporting sanctions may be applied, namely the deduction of up to 10 points automatically upon a club entering administration, along with a maximum time period of 18 months in which a club may be permitted to remain in administration before membership of the league is terminated. The theory behind the policy is that if a football club can shed its debts, it gains an advantage over its competitors and “fair competition” is eroded. The merits of this argument are not apparent. In every league in the world, clubs have differing turnover, expenditure and financial strength. Rangers FC for example, have the largest debts in Scottish football. If Motherwell FC come out of administration and have no debts, will this really impact upon their “competitive” position compared to this half of the Old Firm?

Whether the Football League Insolvency Policy will prove to be successful in terms of “sporting sanctions” and indeed followed in other leagues and countries will be interesting to observe. For example, clubs will have a right to appeal against a sporting sanction but only on grounds of “force majeure”. Indications of what “force majeure” is include that the clubs’ insolvency has been caused by events that are deemed “unforeseeable” and “unavoidable”. The test for each will be interesting and no doubt develop. The introduction of insolvency policies in more associations and leagues throughout Europe has begun and will continue. Indeed, irrespective of their merits, sporting sanctions are likely to become commonplace. By introducing such policies as articles and/or rules to the operation of associations and/or leagues, sanctions will be enforceable against clubs who have unacceptable standards of financial management. Certainly, indulgence for passion in football cannot continue at the expense of fiscal responsibility.

Bruce A Caldow, Sports Practice Group, Harper Macleod

In this issue

- Staying awake, actually

- Keep sane, if not sober

- Obituary – Sheriff Frank Middleton

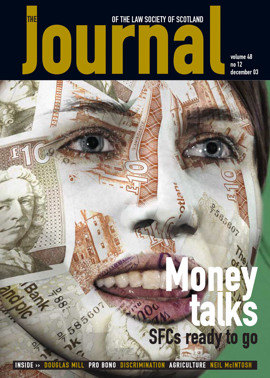

- Money matters

- Clear and present danger

- For love or money

- Setting off abroad

- Legacy giving

- Marking out the pitch

- A merry spam-free Christmas

- Opening up the bench

- Victims find a voice

- Round the houses

- Allowing sexual questioning

- Scottish Solicitors’ Discipline Tribunal

- Discrimination: widening the net

- New rights for farm tenants

- Protection sans frontieres

- Football’s financial red card

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Asbestos safety

- Housing Improvement Task Force

- SDLT: registration requirements