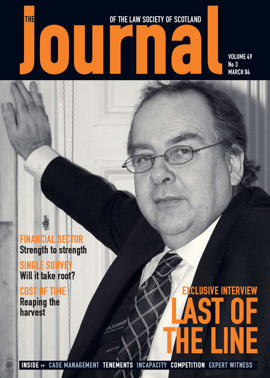

Falconer's safe landing

In a House of Lords debate he was compared to a modern motor tyre which, however grievously punctured, manages to heal itself and roll on undeflated.

Certainly Lord Falconer of Thoroton, Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs and Lord Chancellor has had to weather some heavy criticism since his appointment was sprung on the country last June, as part of the Government’s plans to abolish both the office of Lord Chancellor and the House of Lords as court of final appeal, creating in its place a United Kingdom Supreme Court. Although based on the principle, sound it itself, of taking the judiciary out of the legislature, the proposals have provoked searching questions as to whether they will in fact do any more to guarantee the independence of the judiciary than is achieved at present.

In Scotland two particular charges have been levelled, most notably by the Faculty of Advocates – that the proposals are indeed unconstitutional by virtue of the Claim of Right and the Act of Union; and that they threaten the separate identity of Scots law due to the composition of the court. In his lecture, entitled “Constitutional Reform: Strengthening Rights and Democracy”, it was these points to which Lord Falconer devoted particular attention in defending the Government’s proposals which, he explained, were founded on the principle of enhancing the credibility and effectiveness of our public institutions.

The constitutionality argument centres in part on the role of the Department for Constitutional Affairs, which as successor to the Lord Chancellor’s Department is also responsible for the court service in England and Wales. If the DCA also runs the Supreme Court, said the Faculty, “the existence of responsibility for the courts of England and Wales and the Supreme Court within the same Department would inevitably result in the two jurisdictions being regarded together for administrative purposes”, with the result that for the court to hear Scottish appeals would be contrary to article XIX of the Act of Union. Others take the practical viewpoint that such arrangements would at least result in the court being insensitive to Scottish procedures.

Not so, said his Lordship. “While I am sympathetic to the sentiment, I think the concerns are groundless.” The DCA’s responsibilities, he explained, go well beyond the administration of the courts in England and Wales, extending to the overall management of relations between the UK Government and the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. “The Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs therefore has UK-wide responsibilities which make it entirely appropriate he should take ministerial responsibility for the creation of a new UK Supreme Court.

“In any event the court will have a separate identified fund. The management of that fund will entirely be a matter for the Chief Executive of the court, reporting to the justices.

“These matters will I believe ensure the degree of separateness the Act of Union requires.”

The objection founded on the Claim of Right was addressed by the Lord Advocate at the Law Society of Scotland’s Supreme Court debate on 21 January, in terms which Lord Falconer did not seek to better. The Claim provides: “That it is the right and privilege of the subjects to protest for remeed of law to the King and Parliament against sentences pronounced by the Lords of Session providing the same do not stop execution of the sentences.”

The Lord Advocate commented that it was a difficulty for the Faculty’s argument that the nature of the appeal had already changed by the 19th century, when the appellate committee of the House of Lords took shape and other members ceased to hear appeals. He continued:

“The second difficulty is the proviso… this provision looks to me like a saving of the effect of the judgment against which a protest is being made. In other words… some sort of procedure equivalent to a Lord Advocate’s or Attorney General’s reference. However that may be, the House of Lords itself, on 19 April 1709, only two years after the Union, made an Order enacting that an appeal from a Scottish court prevented execution of the sentence or decree appealed. No-one can have told them that this was unconstitutional!” And the interim execution now permitted by the Court of Session Act, like all other interlocutors in the case, is subject to review by the Lords.

“It is difficult to reconcile the view of the Faculty, that any departure from the Claim of Right is unconstitutional, with what has happened and is happening in fact.”

In light of these views, said Lord Falconer, and the fact that other provisions in the Claim of Right such as the ban on Roman Catholics clearly had no place in modern society, “the Vice Dean of the Faculty of Advocates told me this afternoon that he would now reflect on their position on the Claim of Right”.

Turning to the composition of the court, the Faculty, among others, argued for at least three full time Scottish members, to enable Scottish appeals to be heard by a court with a Scottish majority. Consistent with their general opposition to the use of temporary judges, they maintained it would be unsatisfactory to rely on ad hoc assistance from other qualified judges for this purpose. Lord Falconer was not persuaded.

“While there may be cases where it is appropriate to have a majority of Scottish judges, I think generally the mix works better. In devolution cases, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council has always enjoyed the flexibility to draw on the expertise of holders of high judicial office in each jurisdiction who are members of the Privy Council… In the Supreme Court, this flexibility will be extended across the whole of the court’s work. It will be a matter entirely within the discretion of the President of the court when to draw on additional justices. To preserve the status of the justices of the court, he or she should only be able to use the power sparingly. Where appropriate then, a panel can be composed in which Scottish justices form the numerical majority.”

The Lord Chancellor illustrated the strengths to be gained from a mixed bench using Donoghue v Stevenson. “Here it was the job of the House of Lords not merely to decide where the loss should fall as between the two famous citizens of Paisley, but to consider the principles of negligence applying throughout the United Kingdom (and, as it turned out, the entire common law world). In doing so, it needed to be able to draw upon a bench expert not only in deciding questions of English and Scots law in isolation, but in taking an overview of the relationship between the legal principles in play across both systems of law. It is my belief that we should not, in creating a Supreme Court in the United Kingdom, create an institution which would not be capable of dealing as effectively with a case of the importance of Donoghue v Stevenson should it arise today.”

Questioning from the audience was muted. Lord Hope of Craighead, who has publicly voiced reservations over the proposals, frankly stated that although when the consultation paper was published little thought appeared to have been given to the Scottish position, his concerns had since been addressed. Asking about the role of the Scottish Parliament in the debate, he received the response that without straying precisely into what was devolved, it was plainly right that Westminster should determine whether there should be a UK Supreme Court; that it was for the Scottish Parliament to decide how to debate the topic (as it had done); but that legislation in relation to any devolved questions would have to be dealt with by Sewel motion.

The debate over the Government’s plans will doubtless continue at least until the bill is passed. Still contentious is the whole question of timing against the background of the mishandled launch of the proposals, with many, including the House of Commons Constitutional Affairs Committee, taking the view that publication of a draft bill first is necessary to give proper consideration to such far-reaching reforms, and that the situation should be avoided of the newly constituted court having to use the same House of Lords facilities because no other building is yet available.

Many continue to question the cost-effectiveness of the whole project, given the standing of House of Lords decisions despite the constitutionally anomalous position of the judges, and legitimate doubts remain over what extra funds will be available and what litigants will be expected to pay. But what looked until recently like serious, distinctively Scottish questions may have lost their sting.

In this issue

- Consumers and their guardians

- For the United Kingdom?

- Law meets its maker

- Falconer's safe landing

- Competition and the solicitor

- Flying the flag in finance

- Last piece of the jigsaw

- A good year for most firms

- System addicts

- Putting theory into practice

- The corporate challenge

- Make money out of IT

- A first-rate presentation

- The usual experts?

- Obituary: David Stewart Williamson

- Pearls of wisdom

- Work in progress

- The quality assurance scheme

- Fair hearing with prior knowledge?

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Managing the timetable

- Are landlords' fears justified?

- Caps the stars don't want

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Best foot forward?

- The new law of real burdens