Identity crisis

It has been a vibrant few months in family law since my April column. The Court of Session was faced with a fascinating and unusual case in which the pursuer sought reduction of a decree of divorce on the basis that he had earlier divorced the defender, by means of a talaq in Pakistan (Syed, orse Ahmed v Ahmed, 31 March 2004, Lord Menzies). However it is two English cases, which are likely to have effect in Scotland, that I want to consider this month.

One body, two sexes

I had not intended to return to transgender issues quite so soon after my last column dealt with the Gender Recognition Bill, but then I had not expected the House of Lords to depart so soon and so spectacularly from its decision last year in the transsexual marriage case of Bellinger v Bellinger [2003] 2 AC 467. The fact that their Lordships deny departing in any way at all from that case only serves to heighten the spectacle.

The respondent in A v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire Police [2004] UKHL 21, who was a male to female transsexual, had her application to become a police officer rejected on the basis of her transsexuality. To discriminate in employment against a person because of their transgender status is, of course, contrary to the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (P v S and Cornwall County Council [1996] ECR I-2143), but the chief constable sought to rely on the defence that being of one sex or the other was a “genuine occupational qualification”. This defence is not unique to sex discrimination. It appears also in regulation 7 of the Employment Equality (Sexual Orientation) Regulations 2003 (SI 2003/1661), which permits discrimination if being of a particular sexual orientation is a genuine occupational requirement. (Suggestions are sought as to what sort of occupation requires as a genuine qualification that the employee or prospective employee be either gay or non-gay). The chief constable pointed to statutory rules requiring that when the police undertake intimate body searches only male police officers can search males and only female police officers can search females. He argued that as a male-to-female transsexual, Ms A in law (because of course the Gender Recognition Bill is not yet in force) remains a male and so would be statutorily barred from searching females, but could only be allowed to search males by breaching her privacy and revealing to her colleagues and the public that though she looked female she was, in law, male.

The House of Lords were unanimous in rejecting this defence, on the basis that it would have been within the operational control of the chief constable to exempt Ms A from carrying out such searches at all: this would have been a more proportionate response to the situation than the outright refusal to employ her. But they were not unanimous in deciding how to reconcile their decision with the proposition, originally enunciated in Corbett v Corbett [1971] P 83 and affirmed in Bellinger v Bellinger, that a person born unequivocally (in physical terms) of one gender remains that gender in law all his or her life. The issue will not be entirely resolved by the Gender Recognition Bill, for there will always be some transsexuals who do not seek, or are not eligible for, a gender recognition certificate.

The majority held that the words “woman” and “man” in the Sex Discrimination Act 1975 must be read “as referring to the acquired gender of a post-operative transsexual who is visually and for all practical purposes indistinguishable from non-transsexual members of that gender” (per Lord Bingham at para 11). This means that the definition of “male” and “female” might be different depending upon the issue – and a person may be male for one purpose (say, marriage) and female for another (performing intimate body searches). A transsexual’s new sex is therefore recognised for the purposes of sex discrimination law even without the enactment of the Gender Recognition Bill. Lord Rodger disagreed and held (para 24) that it would be unlawful for a male to female transsexual to carry out intimate searches on a female person: in other words, if Ms A was male for the purposes of marriage she remained a male for the purposes of the rules governing searches.

Lady Hale, at para 59, suggested that it would not be rational for a person to object to being searched, or nursed (for example) by “a trans person of the same sex” (i.e. by a person who is now but was not always the same sex as the person being searched or nursed). Unfortunately, she added (rather gratuitously) that it may be rational to object to being nursed by a homosexual person of the same sex. This comes dangerously close to sanctioning the police using such a so-called “rational” objection to refuse to employ gay or lesbian persons as police officers on the ground that the sexual orientation which permits searches is, rationally, a genuine occupational requirement within the terms of the 2003 Regulations cited above.

Applying different standards

It has long been the rule, as understandable to lawyers as it is incomprehensible to laypeople, that a criminal charge of child abuse may fail because the prosecutor did not meet the standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt, while at the same time the child can be removed from the accused through the child protection mechanisms because the civil standard of proof, the balance of probabilities, has been met. It is this incomprehension that explains the dismay expressed in many sections of the press at the Court of Appeal’s decision in Re LU (A Child) and LB (A Child) [2004] EWCA (Civ) 567. Earlier this year, in R v Cannings [2004] EWCA (Crim) 1, the Court of Appeal had quashed the conviction of a mother found guilty of murdering two of her children, three of whom had died in early infancy. Expert evidence had suggested that the statistical chances of all three children dying in the absence of parental abuse was inconceivably high but the Court of Appeal held that this was not sufficient to satisfy the burden of proof of the mother’s criminal guilt. It was thought that a consequence of this decision was that very many civil cases, in which children had been removed on the basis of expert evidence, were now vulnerable to challenge. The presiding judge emphasised that it was too broad an interpretation of Cannings to say that expert evidence alone is insufficient to justify a conviction or, a fortiori, the application of child protection mechanisms.

Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss P, for it was she, after setting out the familiar standards of proof in criminal and civil proceedings, explained in some detail the reasons why the two processes have different standards: child protection proceedings are quasi-inquisitorial and the function is child protection rather than adult punishment; in criminal proceedings an unjust verdict cannot be analysed, while judges trying family cases make findings of fact in the course of a reasoned judgment which is open to challenge on appeal; material available to the court in child protection cases is likely to be much more extensive than that admitted in a criminal trial. It followed that child protection cases, before and after Cannings, remain to be determined by the balance of probabilities and acquittal on a criminal charge does not necessarily lead to the absolution of the parent in family or civil proceedings. The effect of Cannings on child protection proceedings had been “over-estimated” in some quarters.

Butler-Sloss P also took the opportunity to restore to its position as the guiding principle the statement of Lord Nicholls in Re H (Minors) [1996] 1 All ER 1 that “the more improbable the event the stronger must be the evidence that it did occur before, on the balance of probabilities, its occurrence will be established”. This is consistent with the earlier statement of the Second Division in the children’s hearing case of B v Kennedy 1987 SLT 765 that “the weight of evidence required to tip the scales may vary with the gravity of the allegation to be proved”. It is to be remembered that if new evidence comes to light after child protection proceedings in Scotland, a rehearing of the evidence upon which these proceedings were based can be sought under section 85 of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995. A change in scientific understanding, or the discrediting of a scientific theory, or indeed of an individual expert witness, upon which the original finding was based would, it is submitted, amount to new evidence for this purpose. But as LU (A Child) and LB (A Child) shows, while such new evidence may make a criminal conviction unsafe, it may not in itself lead to a finding that a ground of referral to a children’s hearing can no longer be accepted as having been made out on the balance of probabilities.

Kenneth McK Norrie, Professor of Law at the University of Strathclyde

In this issue

- Pushing ahead with a modernising agenda

- Equality for the employed

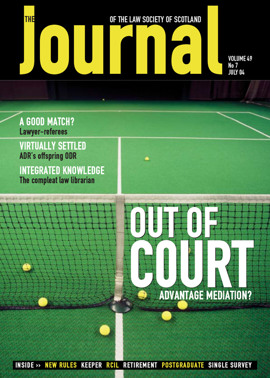

- Break point

- The devil in the detail

- The work goes on

- Identity crisis

- The lawmen in black

- Degrees of insight

- Image and reality

- Terminal settlement

- The informed client

- Counting down

- Speaking for the firm

- Does the EU Regulation work?

- Power to the people?

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- New build: getting the loan funds

- Keeper's Corner

- RCIL and community rights