A neglected asset

Research published last year by IT industry body, the Business Software Alliance, found the UK to have a software piracy rate of 27%. According to this figure, over one in four software applications running in Britain was being used illegally (http://management.silicon.com/government/0,39024677,39130560,00.htm). The Alliance further warned recently that the number of its investigations into the illegal use of software by British business had increased by 23% year on year.

The figures make for alarming reading and conjure up visions of vast swathes of the country engaged in copying and distributing illegal copies of software. The truth of the matter is in fact, thankfully, less disturbing. While counterfeiting may be the most heavily publicised form of piracy, other, less obvious behaviour can also result in a business inadvertently running illegal software.

For each software program a business uses, it needs a licence. Using the software outside the terms of the licence is an infringement of copyright, typically referred to as software piracy. Besides making and selling illegal copies of software, infringement of copyright can also include:

- installing software on more computers than the licence allows;

- allowing employees or contractors to make copies of software without the required licence;

- using copies of illegal software, even unknowingly;

- allowing or asking an employee or contractor to install software on a PC without holding the requisite licence.

Ignorance the enemy

The BSA’s figures can be largely accounted for by a lack of understanding of software holders’ user rights. And in businesses, the absence of a process to manage software usage across an organisation can also be to blame.

Broadly speaking, software can be purchased in three different ways depending on the number of users: as a packaged product direct from a retailer or reseller; as pre-installed software on newly-purchased PCs; or through a volume licensing agreement.

Each method of purchasing licences for software can, if an organisation is not on its guard, expose it to the risks of running illegal software. Organised crime rings around the world are engaged in producing high-quality counterfeit software, which is often extremely sophisticated in its attempts to replicate packaging, logos and anti-piracy security measures. Organisations purchasing fully-packaged product should be sure to buy from reputable retailers or resellers recommended by the software vendor to avoid the risk of purchasing high-quality counterfeit software. It is worth also noting that retail software may be transferred in its entirety to a different computer system only if the program is deleted from the other PC.

Best precautions

Businesses opting to purchase software pre-installed on new PCs should be sure to ask for the original genuine media and documentation as proof of ownership and that the software is fully licensed. Demanding this documentation guards against the activities of those unscrupulous PC vendors that copy software directly on to a machine prior to purchase without having the appropriate licensing agreement in place. Licences obtained in this way – so called OEM licences – are these days generally single-use licences, meaning that they live and die with the hardware they were purchased on, and cannot be installed elsewhere.

Many businesses choose to purchase software under volume licensing agreements, which give them the right to operate a set number of particular programs across the organisation. The risk of running illegal software in these circumstances stems from under-reporting on the number of programs in use. Amidst the everyday pressures of urgent deadlines, demanding clients and managerial responsibilities, keeping track of all the software in use at the business can seem like an unnecessary and onerous task. However, maintaining legal software should be an important part of any corporate governance strategy.

The management process

Irrespective of the route chosen to purchase software, what is needed is to put in place a process that coordinates and manages the installation, removal, upgrade and usage of software across the business. This process is called software asset management (SAM) and it provides the framework needed to control the business’s software effectively through all stages of the product’s lifecycle.

There are four main steps in implementing a SAM process:

- conducting a software inventory;

- matching software licences acquired with software installed;

- updating company policy and procedure governing software use;

- developing a software asset management plan.

The first step towards creating a framework for managing software in the business is to establish exactly what software the business currently has installed. At smaller firms this may be done manually by simply visiting each PC and viewing the “add or remove programs” screen which tells you exactly which programs are running. Larger firms may need to use special tools which scan a network and the PCs connected to it to produce a full inventory.

Next begins the process of locating the company’s software licences and drawing up a spreadsheet to record the number of licences held compared to the number of programs installed. End-user licensing agreements (EULAs) outline the terms and conditions for software acquired. For customers who have purchased retail software or received it pre-installed on PCs, the EULA is commonly found in one of three places: on a document accompanying the software; printed in the user manual; or within the software application. Businesses participating in a licensing scheme can find details on the number of software applications covered in their original agreement.

Consider whether the organisation needs all the programs installed. After that, any shortfall in the number of licences held compared to the number of programs installed means that the business should approach their local technology consultancy to acquire additional licences.

After these first two steps to bring a company’s software licensing situation up to speed, the next stage is to put in place procedures to govern software acquisition and usage in the organisation, and prepare for unexpected disasters.

To do this, the following documents should be developed or reviewed:

- software acquisition policy, to describe procedure for employees needing new software;

- software check-in list to determine where responsibility lies for registering new software in the company’s inventory;

- software use policy to cover the organisation’s rules for downloading, installing and using software programs;

- disaster recovery plan to cover how software assets will be restored in the event of a catastrophe.

The final stage is to create a plan that will ensure the business retains the control it has gained of its software and licences. It is advisable at this step to standardise applications and retire obsolete PCs, servers and software throughout the organisation. Doing so will reduce the support time needed to keep on top of numerous differing software packages. Once this is completed, regular software inventories should be scheduled. Their frequency depends on a number of factors: the size of organisation; software acquisition habits; and rate of staff recruitment. Carrying out periodic spot checks may also prove useful in large organisations. This final step completes the implementation of a SAM framework to ensure that software throughout the business is being used legally.

Business benefits

The benefits of software asset management extend however far beyond holding the correct number of licences, and bring advantages to all areas of the business. Introducing SAM means that the organisation avoids paying for licences it isn’t utilising. In continually monitoring the applications held on the company’s hardware, it can also ensure that the stability of the technological infrastructure is not threatened by the installation of unauthorised software. Using licensed software also grants eligibilty for technical support and product upgrades.

Implementing SAM also puts the business on a firm footing to take full advantage of volume licensing programmes. While acquiring software on an ad hoc basis from retailers or pre-installed in new PCs is a suitable approach for some businesses, volume licensing agreements offer others the ability to plan for business software requirements over a longer period. They provide flexibility to cater for growth, as licences for additional software can be obtained quickly and cost-effectively. Payment for software can be made in instalments and factored in to long-term budgets, bringing stability to financial planning. Free consultancy on the installation and deployment of new software can be called on as required to take the uncertainty out of necessary technology upgrades.

Having in place a SAM system provides the necessary foundation to plan the installation, usage and retirement of software, along with the activation of licensing benefits, to help the business meet its long-term strategic goals.

Given that software is such a critical tool for most modern businesses, it is surprising that so little attention is given to its management, documentation and upkeep after the initial purchase. Essentially, software is taken for granted. In order for organisations to get the most out of their technology investments, it is time for software to be treated as an asset and managed as such. Just like software, SAM is vitally necessary in today’s business world.

Ram Dhaliwal is Microsoft UK Licensing Manager

In this issue

- Legal aid in children's hearing referrals

- Still waters run deep

- Catch-up or patch-up?

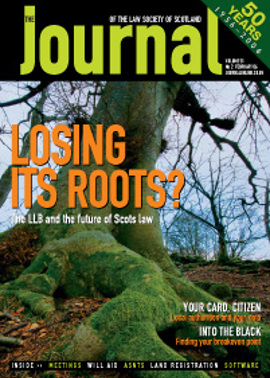

- Legal science or law-lite?

- Heads above water

- Your name on file

- A welcome addition

- Another ***** meeting?

- A neglected asset

- Planning a year of action

- The Pagan mission

- A good case to read

- Jurisdiction: dispelling the myth

- That special something

- The art of cashing in

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- In on the Act

- Keeper's corner