All that sparkles ain't gold

Que sera, sera

When I was just a little girl

I asked my mother

What will I be?

Will I be pretty?

Will I be rich?

Here’s what she said to me:

Que sera, sera

Whatever will be, will be

The future’s not ours to see

Que sera, sera

What will be, will be

The promotional structure in Scottish private practice has remained essentially unchanged for decades. Qualify, work hard and you are in with a chance to attain the elusive prize most coveted: to become an equity partner. Those who have attained partnership are justifiably proud of their achievement and mark their staff’s career progression in the same way. But is the structure still appropriate?

The promotion ladder

The majority of solicitors today have worked extremely hard to get to where they are. That applies equally to those at the start of their careers as to those with years of practice under their belts. Most entrants into the profession have done a four year honours degree, with a year’s postgraduate study and a two year traineeship before they reach qualification level. The number of available traineeships is outstripped by the number of graduates with law degrees. Those who get Diploma places and traineeships take a hefty burden of debt with them due to the lack of suitable funding for tertiary education, and the average student debt currently stands at around £10-15,000. The competition to get a university place at all means that young people who have overcome these hurdles to join the profession performed at school within the top 5% of students in Scotland. Take a strong academic background, mix it with a long, highly competitive training period and add a generous helping of student debt, and you have a generation of highly motivated lawyers who are used to succeeding and have high expectations from working life.

In the 70s, the reward for investment, flexibility, loyalty, dedication and hard work with a firm in private practice was a serious shot at equity partnership after around five years of qualification, in some cases even earlier. Equity partnership is still the carrot most commonly used today. In general, the promotional ladder in private practice firms follows a fixed path: (1) trainee; (2) assistant; (3) associate; (4) partner. Some firms offer slight deviations, such as “senior assistant”, “senior associate”, “consultant” or “senior solicitor” to indicate seniority and/or capability. Most firms also offer salaried partnerships or lockstep arrangements leading to equity status. Promotion within this framework is earned if a solicitor can demonstrate a solid track record in a range of skills such as billing performance, expert status, client relationships and an ability as a “rainmaker”.

However this structure leaves a massive gulf between assistant and partner. Interim labels are said to indicate the seniority and/or expertise of the individual concerned within that gap. But is this really what they mean? Do they represent a genuine reward and recognition of worth, or are they just “holding bays” for those on the route to partnership, designed not to make people feel valued but to persuade them not to jump ship to a competitor firm? Worse still, could they be no more than an additional barrier to partnership?

Partnership: vision or mirage?

The legal marketplace has changed beyond recognition within the last 30 years. The majority of entrants in the profession are now women. The majority of practising solicitors are under 40 and in-house lawyers are now the fastest growing legal sector.

Private practice is changing. In general, firms are fast splitting into one of three categories: (1) large firms; (2) middle sized (largely specialist) firms; and (3) small 1-3 partner firms. This picture will change again with the introduction of multi-disciplinary partnerships (and variations thereof) and the invasion of American and English firms, who recognise the attractions of Scottish solicitors as an extremely effective and economic workforce. Most law students aspire to work for the large firms but fail to realise that the route to reaching partnership there is fiercely competitive, with challenging hurdles and a necessity for excellence in all of the “partnership” skills. Partnership skills are not of course just about excellence as a lawyer, and when solicitors realise that they also include a mix of interpersonal and management skills they look to their firms for a clear definition of how to learn and to meet the criteria. Unless you’re lucky, many firms won’t define the “soft” attributes that they look for in a partner and will not appraise your performance in these areas in a meaningful way.

Continuing for the moment on the assumption that partnership is as much a goal as it ever was, there is real doubt as to whether there are enough partnerships and associateships out there to give every ambitious solicitor a genuine stab at promotion. There is only so much room for profit-sharing partners. Second-tier salaried partners/ associates keep the gearing in check. Many firms still insist that partnership is an attainable goal for any solicitor if you work hard enough, but experience shows that this is not practical or realistic. The financial pickings would get slimmer for everyone. How then do you keep your staff fulfilled and motivated once that penny has dropped? Do labels just put up additional hurdles to the equity goal of running the business?

Valid alternatives

Perhaps the real question that private practice should be asking is whether the assumption still holds. Is partnership is still the ultimate goal for all solicitors? Those who don’t seek out partnership are sidelined and labelled as “jobsworths”, but is this sensible? Few partners (bearing the scars of their own battles to partnership) question whether the assumption remains valid, but anecdotal evidence suggests that partnership for modern lawyers is not the golden fleece it once was. Provided solicitors are adequately paid for their contribution, other aspects become more important. Career/life balance is commonly quoted by solicitors as being of primary importance in determining job satisfaction – rating higher than salaries. The mass exodus of (predominantly female) solicitors at five years’ PQE also suggests that partners are missing a trick. Could it be that our highly ambitious, highly trained, career motivated lawyers find something lacking?

Evidence for this theory lies in the increase of solicitors moving in-house. Easily the fastest growing sector, in-house lawyers enjoy a far more flexible career structure, geared around the bandings used within each employer organisation. The usual labels are spurned in favour of promotional bandings, team structures and clearly defined areas of responsibility. “Partnership” in-house is more clearly recognised for what it is – a move into management and away from a daily legal caseload. Solicitors in-house have flexibility allowing them to develop their careers in a more fluid manner. They often reap real benefits from company policies on work/life balance and flexible working arrangements, all of which allows mid-level solicitors the flexibility to continue working in a challenging profession, taking on quality work that they get recognition for, contributing in a tangible fashion whilst pursuing interests in their private lives.

Final thoughts

Private practice needs to respond if it wants to stem the brain drain. Paying lip service to work/life balance is insufficient, and the culture of private practice must evolve to meet the realities of working life in the 21st century. Firms must evolve to offer a reward system that recognises contribution with something tangible as an alternative to partnership: perhaps something akin to share option schemes. The expectations of lawyers have changed. Many would relish the opportunity for a job that offers a real work/life balance but retains and uses their skills without the stigma of not pursuing partnership. More creative solutions are required. Solicitors recognise the carrot but will vote with their feet if private practice does not respond. Que sera, sera is not good enough.

The author is a solicitor in private practice

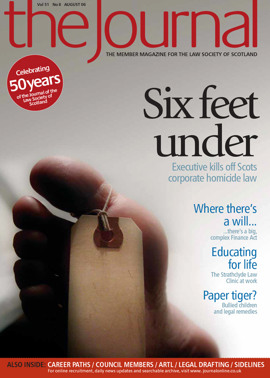

In this issue

- Ireland 4, Italy 0

- A lack of trust

- Technology and the Scottish courts

- For supplement read tax - an update

- Eyes on the ball

- Don't leave gaps in regulation

- Keeping company

- Fighting the bullies

- The university of life

- A lack of trust (1)

- With these few words...

- Tell it like it is

- All that sparkles ain't gold

- PDF is the standard

- The paper monster

- Safeguarding fair trial

- New law, new problems

- Raising the stakes

- Mark the pre-proof

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- It takes two to tango

- Land attachment and suspensive missives

- PSG's suite moves