Ireland 4, Italy 0

The long-awaited decision of the European Court of Justice in the case of Euro Food IFSC Ltd was handed down on 2 May 2006. Readers may recall that this case originates from the extraordinary administration of Parmalat, the Italian food company. Euro Food was incorporated in the Irish Financial Services Centre and its principal purpose was to provide finance to other Parmalat subsidiaries.

Summarised briefly, following the collapse of Parmalat, Bank of America NA began compulsory winding up proceedings against Euro Food in the Irish High Court on 27 January 2004. A provisional liquidator was appointed the same day. On 9 February 2004 in Italy the extraordinary administrator of Parmalat was appointed as the extraordinary administrator of Euro Food. On 20 February 2004, the district court in Parma decided that Euro Food’s centre of main interest was in Italy and that it had jurisdiction to determine that it was in a state of insolvency. On 23 March 2004 the Irish High Court held that the centre of main interests of Euro Food was in Ireland, that the proceedings opened in Ireland were main proceedings and further that the circumstances of the Italian courts’ ruling were such as to justify the refusal of the Irish courts to recognise the decision of that court. The Irish High Court then made an order for winding up appointing the provisional liquidator as liquidator. That decision was appealed by the Italian extraordinary administrator and in that appeal the Irish Supreme Court referred the five questions concerning the interpretation of the EC Regulation on Insolvency Proceedings (Regulation 1346/2000) (“the Regulation”) to the European Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling.

The questions referred were:

1 Where a petition is presented to a court of competent jurisdiction in Ireland for the winding up of an insolvent company and that court makes an order, pending the making of an order for winding up, appointing a provisional liquidator with powers to take possession of the assets of the company... does that order combined with the presentation of the petition constitute a judgement opening insolvency proceedings for the purposes of the EC Regulation?

The ECJ said yes – it is a decision by a court of a member state based on the debtor’s insolvency where that decision involves divesting the debtor of his assets and appointing a liquidator as referred to in Annex C to the Regulation. In order to ensure the effectiveness of the EC Regulation the "recognition principle" should be capable of being applied as soon as possible. The ECJ therefore concluded that a decision to open proceedings should not be limited to decisions formally described in the member state local courts as a decision in the proceedings. This, however, may encourage "forum shopping", and we can also anticipate a further raft of amendments to the annexes to the Regulation to include temporary administrators/liquidators.

2 The Irish court’s second question assumed a negative answer to question 1 and it was therefore unnecessary for the ECJ to answer this question.

3 The third question was whether the effect of the Regulation was that a court in a member state other than that in which the registered office of the company is situated and other than where the company conducts the administration of its interests on a regular basis and in a manner ascertainable by third parties, but where insolvency proceedings were first opened, has jurisdiction to open main insolvency proceedings. Article 3(1) of the Regulation provides that in the case of a company or legal person the place of the registered office shall be presumed to be the centre of its main interests in the absence of proof to the contrary.

The ECJ answered this question on the basis that on a proper interpretation of article 16 of the Regulation, the main insolvency proceedings opened by a court of a member state must be recognised by the courts of the other member states without the latter being able to review the jurisdiction of the court of the opening state. The ECJ held that it was incumbent on the court of a member state hearing an application for the opening of main insolvency proceedings to check that it has jurisdiction in terms of article 3(1) of the Regulation.

4 The fourth question which the Irish court asked was what factors were to be taken into account in determining the centre of main interests (COMI). In particular, where the registered offices of a parent company and a subsidiary company are situated in two different member states, is the determining factor the power to control the policy of the subsidiary, or the conduct of administration of the subsidiary?

The ECJ held that the COMI must be identified by reference to criteria that are both objective and ascertainable by third parties, ensuring legal certainty and foreseeability concerning the determination of the court with jurisdiction to open the insolvency proceedings. The simple presumption in favour of the registered office can be rebutted only if factors which are both objective and ascertainable by third parties exist which locate the COMI other than at the registered office. The ECJ stated that that could be so in particular in the case of a “letter box” company not carrying out any business in the territory of the member state in which its registered office is situated.

They then held that by contrast where a company carries on its business in the territory of the member state where its registered office is situated, the mere fact that its economic choices are or can be controlled by a parent company in another member state is not enough to rebut the presumption laid down by the Regulation. This guidance is of course incomplete. What is not clear is whether the ECJ intends to go so far as to imply the converse of a letter box company namely that where a company carries on any business in the place of registration the presumption cannot be rebutted. The judgment does not appear to go as far as that but leaves room for such an argument.

Somewhat unhelpfully, the ECJ does not address the “head office function” test which had been approved in the Advocate General’s opinion and which has been followed recently in the French courts.

5 The last question reflected concerns that the (Irish) provisional liquidator had not been given sufficient opportunity to be heard in Parma, and was whether, where it is manifestly contrary to the public policy of a member state to permit a judicial or administrative decision to have legal effect in relation to persons or bodies whose right to fair procedures and a fair hearing has not been respected in reaching such a decision, that member state was nevertheless bound by the Regulation to recognise the decision of the courts of another member state purporting to open insolvency proceedings, where the court of the first member state is satisfied that the decision in question has been made in disregard to those principles and where, in particular, the applicant in the second member state has refused (in spite of requests and contrary to the order of the court of the second member state) to provide the provisional liquidator of the company duly appointed in accordance with the law of the first member state with any copy of the essential papers grounding his application.

The ECJ considered that recourse to this provision could be envisaged only where recognition or enforcement of the judgment delivered in another member state would be at variance to an unacceptable degree with the legal order of the state in which enforcement is sought in as much as it constituted a manifest breach of a rule of law regarded as essential in the legal order of the state in which enforcement is sought. The ECJ considered the right to be heard and to be notified of procedural documents occupied an eminent position in the organisation and conduct of a fair legal process and that the "equality of arms" principle was of particular importance in insolvency proceedings. Any restriction on the exercise of the right to be heard must be duly justified and surrounded by procedural guarantees ensuring that persons concerned by such proceedings actually have the opportunity to challenge the measures adopted in urgency.

The ECJ therefore decided that a member state may refuse to recognise insolvency proceedings opened in another member state where the decision to open the proceedings was taken in flagrant breach of their fundamental right to be heard which a person concerned by such proceedings enjoys. The ECJ also observed that a national court cannot simply impose its own concept of what is required on the court of another member state but should assess whether the parties were given sufficient opportunity to be heard. In this respect the ECJ’s judgment may be considered uncontroversial.

It will now be interesting to see how and how quickly the remaining issues in relation to jurisdiction and the determination of the centre of main interests of a debtor are resolved.

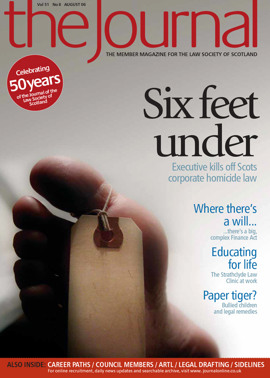

In this issue

- Ireland 4, Italy 0

- A lack of trust

- Technology and the Scottish courts

- For supplement read tax - an update

- Eyes on the ball

- Don't leave gaps in regulation

- Keeping company

- Fighting the bullies

- The university of life

- A lack of trust (1)

- With these few words...

- Tell it like it is

- All that sparkles ain't gold

- PDF is the standard

- The paper monster

- Safeguarding fair trial

- New law, new problems

- Raising the stakes

- Mark the pre-proof

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- It takes two to tango

- Land attachment and suspensive missives

- PSG's suite moves