New law, new problems

After much delay and debate we now have reforming legislation with the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006, which came into effect on 4 May 2006. Arguably the Act creates as many difficulties as it was intended to solve.

One key area of family law practice affected by the new legislation is that of financial provision on divorce where matrimonial property is likely to be the subject of transfer between spouses. This may be from joint names to a single name or a wholly owned asset from one spouse to the other. The method by which we value such matrimonial property has changed and consequently the ingathering of information and the compilation of a schedule of matrimonial property is likely to become a more complicated task.

The core provisions relating to the valuation and division of matrimonial property are found at s 10 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985, which provides that the net value of matrimonial property is to be identified and valued at the “relevant date”, usually, but not always, the date of separation.

The old problem

Historically this method of valuing and dividing matrimonial property led to difficulties where an asset had increased in value after the relevant date. This problem has been conspicuous in recent years when property prices have risen sharply. The now notorious case of Wallis v Wallis 1993 SLT 1348 (HL) dealt with the scenario in which the matrimonial home had risen in value between the relevant date and the date of decree of divorce, but did little to develop the law in Scotland.

Under the old law, where the matrimonial home (often jointly owned) was to be transferred to one spouse, the spouse acquiring the property effectively received a “windfall” if the property had increased in value by the settlement date (or divorce). That was an inevitable consequence of the court making a transfer order because of the provisions of s 10 of the 1985 Act. The fact that the value of the matrimonial home had increased substantially between the relevant date and the date of divorce was not per se a “special circumstance” that justified a departure from the principle of equal sharing. This led to apparent and actual unfairness in many cases.

The attempted solution

In terms of the amendments made to s 10 by the 2006 Act, s 16, where an asset is to be transferred to a party by virtue of a property transfer order, the “relevant date” is replaced by that of the “appropriate valuation date”. In practice that is likely to mean “current value” in most cases.

The appropriate valuation date will be either:

- the date agreed by the parties to the marriage (1985 Act, s 10(2A)(a), deemed to apply by 2006 Act, s 16(b));

- the date of the making of the property transfer order (deemed s 10(2A)(b));

- where the court considers that the case involves exceptional circumstances, and determines that s 10(2A)(b) shall not apply, any other date as the court may determine (deemed s 10(2B)).

Under this new regime, a valuation of the asset in question which may be the subject of a property transfer order should be obtained as at the relevant date and at the appropriate valuation date. Practitioners may wish to frame a schedule of matrimonial property showing both valuations in order to facilitate negotiations.

New uncertainties

The alternative valuation date is not always going to be easy to determine when parties are in dispute as to whether an asset should be transferred or sold. The alternative valuation date may effectively be determined only after a diet of proof. This will also be true of a case in which “exceptional circumstances” are averred in terms of the deemed s 10(2B) of the 1985 Act.

In cases which do proceed to proof, it is unclear how the alternative valuation date will be determined. Conceivably it could be deemed to be the date of the conclusion of the proof or the date of the issue of the judgment, or indeed any date in between. It is not difficult to conceive of a scenario in which the valuation date determined could make a real difference to the value of the matrimonial property. For example, the value ascribed to a shareholding could alter substantially overnight. The alternative valuation date would be of key importance in a scenario where a significant portion of the matrimonial property was made up of such assets and where the claimant spouse seeks a property transfer order rather than a capital sum or an order for sale.

It remains to be seen how the provisions will be interpreted and applied in practice by the courts. What is apparent is that whilst the Wallis issue may have been addressed, there remains some uncertainty.

Amanda Masson is a member of the Morton Fraser Family Law Team, based in the Glasgow office

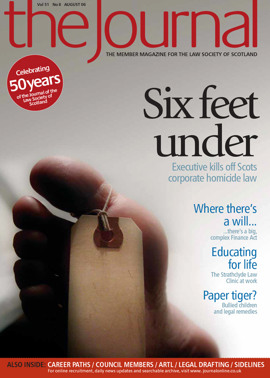

In this issue

- Ireland 4, Italy 0

- A lack of trust

- Technology and the Scottish courts

- For supplement read tax - an update

- Eyes on the ball

- Don't leave gaps in regulation

- Keeping company

- Fighting the bullies

- The university of life

- A lack of trust (1)

- With these few words...

- Tell it like it is

- All that sparkles ain't gold

- PDF is the standard

- The paper monster

- Safeguarding fair trial

- New law, new problems

- Raising the stakes

- Mark the pre-proof

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- It takes two to tango

- Land attachment and suspensive missives

- PSG's suite moves