The university of life

Recent Journal articles have generated much debate over the suitability of the LLB degree as a training for legal practice. Whatever the rights and wrongs of that issue, at least one academic is actively involved as a legal adviser to the extent of providing a forum for his students to undertake that role from an early stage.

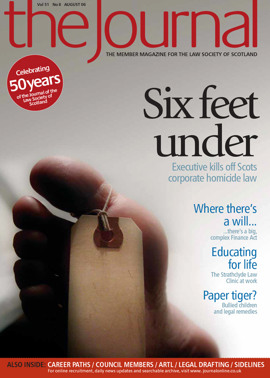

When Professor Donald Nicolson of the Law School at Strathclyde University launched what is claimed to be the only university law clinic in Scotland in October 2003, one sceptic claimed it wouldn’t last longer than two months once the calls started flooding in. Almost three years later, the professor has seen his brainchild grow rapidly to a point where it is now appealing for support from the legal profession in order to continue its work.

Though largely student-run, the primary aim of the Strathclyde clinic is to help in areas of unmet legal need, rather than to provide an educational experience – which it undoubtedly does all the same. What comes as a surprise to the uninitiated is that the client-facing contact is carried out by students, even those at an early stage of their degrees.

Guiding hands

Nor are there many limits on the types of work the clinic undertakes. “We make clear to clients that we will not act for them if they can afford a lawyer or qualify for legal aid”, Nicolson explains. “This means that we will almost never take on criminal cases and are also very reluctant to become involved in divorce and family disputes over children.” That leaves plenty of scope for the budding adviser – while consumer law, housing, employment, and landlord and tenant issues have provided the bulk of the 300 or so individual cases dealt with to date, there have been at least 17 other areas of law covered, from delict through planning law and succession law to intellectual property.

The professor himself rose through the ranks, first as a student adviser and then clinic manager at the fully student-run law clinic of the University of Cape Town. Ten years ago he moved to the University of Bristol where he set up and then for five years ran the now well-established law clinic there, which operates on the same lines as that at Strathclyde.

So how does the clinic achieve the provision of competent advice by those just becoming familiar themselves with the basics? Intending volunteers are vetted at interview, not just for their suitability as advisers but to assess their level of commitment to what can be a time-consuming role, and something they are expected to put ahead of other extra-curricular activities. A two-day training course then covers client interviewing, case management, legal aid, legal research and letter writing. Once into the advisory role, further training can follow in, for example court or tribunal procedure, or advocacy. The Law Society of Scotland, Legal Services Agency and others have provided support in the form of course places. “Any student who has failed to fulfil his or her duties adequately may be given an informal warning by his or her case manager, a formal warning by myself (a ‘yellow card’) or in extreme cases expelled from the clinic”, says Nicolson.

When it comes to individual cases, the short answer to the question is, with a great deal of input from Professor Nicolson. Working in pairs to balance levels of experience, students carry out an initial interview with the client to obtain the facts and ascertain the client’s objectives. They send the professor a summary, and he discusses with them what legal research they should undertake and what practical steps can be taken to further the client’s interests, which may involve seeking further information from the client. Before students can deliver advice, they must write it out, with Nicolson checking it, consulting specialist outside volunteers if necessary. Advice is presented in writing to the client by letter or at interview (the client signing and returning a copy) – though with complicated and potentially risky cases, the professor himself will attend an advice-giving interview. Experienced case managers also keep a close eye on progress and provide advice on appropriate steps where necessary.

Nurturing pro bono

While open to all undergraduate law students and those on the Diploma at the GGSL, membership of the clinic is not for the dabbler. “Through experience, our committee has realised that applicants who are able to demonstrate an interest in social justice make far better and more reliable advisers than those merely seeking to enhance their CV”, Nicolson comments. With over 120 current members, that does say something about the level of student commitment to helping the less well off, and it is a commitment the clinic hopes they will carry into their subsequent careers in whatever way.

“All clients are told that the help they will receive is not that of professional lawyers, but students who are studying to be lawyers, who will consult with academics who do not have professional qualifications or experience, and with me who has years of law clinic experience”, the professor adds. “All clients will be offered, at a minimum, legal advice, and in addition, where appropriate, representation on their behalf in making demands for redress, negotiating settlements and other forms of redress, and advocacy in the small claims court, tribunals and administrative hearings. We generally do not offer to represent clients in other courts, though if the client is aware of the risks involved we might consider acting in the lower courts.”

The clinic does attempt to settle disputes out of court where this is in the interests of justice, avoiding for the client as it does the risks and stresses of litigation, and in its first year it managed to resolve all cases in this way. Since then, however, its growing reputation has attracted increasing numbers of cases already before the small claims court or various tribunals; and the growing complexity and seriousness of matters coming to the clinic at an early stage are increasing its involvement in formal legal proceedings.

Management skills

Apart from Professor Nicolson himself, who acts as chairman, the running of the clinic is also largely in the hands of student volunteers who make up an executive committee, acting under the advice of a management committee drawn from the university, legal profession and local community. Further important skills are learned through the executive committee’s role in organising training, deciding on membership applications and ethical issues, securing funding and dealing with outside organisations.

The advisory team is organised into four “firms”, each headed by a case manager (also a student) who screens potential clients for suitability, allocates cases and inspects client files to monitor progress and quality of service. The clinic now has its own detailed “Good Practice Guide” and attempts to keep as a minimum to the Law Society of Scotland’s own standards of ethics and professional conduct.

Such a level of operation is now reaching a critical point. “In its first two and a half years the clinic exceeded all expectations in terms of both the number and type of cases handled, and what could be achieved on behalf of clients”, Nicolson maintains. “Indeed, our success rate in negotiations and in court is extremely high (for example, we have won 26 out of 28 small claim cases, and are currently appealing one of the losses.” Legal firms and even sheriffs have referred cases to the clinic that might otherwise have had to be presented by party litigants.

Looking to expand

Nicolson has considerable ambitions for the clinic’s the next two to three years. “I would like to see it provide an expanded, but no less proficient, service to those in Glasgow who require our assistance, an expansion into western Scotland, and greater provision of court and tribunal representation. I would also like to extend the role that clinical legal education plays in the Law School so that more students can gain academic credit for their hard work and can obtain the opportunity to improve on their practical legal skills. Most importantly I would like to have in place permanent funding to support these developments and other more long-term plans, such as community legal education and a focus on those most in need of our services, such as immigrants, the homeless and the victims of domestic abuse.”

For this to happen, resources will be needed on various fronts: additional funding to supplement the clinic’s current £5,000 annual budget (plus hidden expenses covered by the Law School), and volunteer help from the profession to support Professor Nicolson, who cannot continue to oversee all advice due to other university commitments. Two Glasgow solicitors, Charles Hennessy and Gerry Kelly, already give up a lot of their time to provide expert help when needed; Nicolson hopes for wider support from the profession.

“In the future we hope to obtain assistance from the profession in two ways. The first is to develop a list of lawyers prepared to give up a few hours a few times a year to be available to give instant advice to clients at drop-in clinics and at the outreach clinics which are planned for various localities in western Scotland. The second is through major financial sponsorship and training support from one or more large firms. In return, they would be raising their profile amongst students, possibly have the students visit their firm for training and would be able to boast pro bono involvement. In addition, if appropriate, their trainees and newly qualified lawyers could gain practice in acting as advocates for clinic cases.”

Traineeship prospects

The project surely offers one avenue to satisfy those solicitors (the majority, if this month’s letters page is anything to go by) who support more practical experience for students at undergraduate LLB level. While Nicolson does not yet have the empirical evidence to claim that clinic advisers benefit directly in their degree results – though such a correlation has been found at the University of Kent – he does assert: “This seems to be the case here at least in the sense that the clinic attracts some of the best students and in past years has had some of the most outstanding students I have taught. Of course, the time taken over clinic work might hamper the poorer students in obtaining good results, though they will still emerge as better prospective lawyers than their colleagues. What is very clear is the advantage clinic students have in training contracts interviews, which tend to focus largely on their clinic experience, and in actually obtaining contracts.”

Could it even encourage firms to take on trainees when they might otherwise hesitate to do so?

The advisers’ tales

“When you go into your first class on say contract law, it’s not exactly Kavanagh QC and people’s image of law is somewhat different when you’re just having to read through textbooks. I was somewhat disappointed with law until I came to work here and realised that the work I did on contract law is relevant when I do this. It’s good to see where you’re putting your knowledge eventually.”

Stuart Kelly is a second year undergraduate on the LLB who has been a member of the Law Clinic for the past 18 months. Now on the executive committee and involved in liaising with legal firms, for him the clinic was a deciding factor in choosing his place of study.

“We’re not against the law firms, we’re out to support them and support the community”, he replies when asked why solicitors should support the clinic. “I’d hope that they’d see us as being potential colleagues, aiding them in trying to help the court system especially, trying to filter cases out and trying to help people who otherwise wouldn’t be helped. I hope that our efforts will help improve the image of the legal community as a whole.”

His colleague Aidan West, completing two years on the graduate entry LLB course, agrees. “What we do is we give lawyers the choice of either facing law students who are going to be impartial and know their procedure or facing a party litigant, and I think they’re going to be best served by facing us because we’re willing to negotiate always and we can explain the issues to the client and I think it’s just very beneficial to the whole legal community.”

When we meet, Stuart has just done his first small claim preliminary hearing and Aidan, who has chosen to focus on employment cases, is about to face his first remedies hearing. While a number of mainly small firms already support the clinic, its student advisers experience a mixture of reactions from the profession, ranging from full co-operation to being given the cold shoulder in court.

“Lawyers sometimes co-operate, sometimes don’t. But it’s better for solicitors than dealing with an emotional client”, observes clinic administrator Aimée Asante.

“I think they should do everything to support us simply because we are the future, we are tomorrow’s lawyers. Also they want to get the top students and quite a lot of them pass through the Law Clinic.”

For the students too, it helps them see where their strengths and weaknesses are, as well as which areas of law are likely to prove of lasting interest. “I’ve now experienced law, seen the less glamorous part, but I’m still keen to go into it. I hope it will make us better lawyers”, says Stuart. And all of them agree that working with the clinic greatly improves their chances of securing a traineeship.

But equally they point to the desire to help others as part of the motivation as much as pursuing their own interests. “It is actually a good feeling when you get a good settlement for a client”, Aidan comments. Stuart concludes: “We have thank you cards on the wall, they’re always streaming in, people who are genuinely grateful for what we do and it’s rewarding to be able to help them.”

In this issue

- Ireland 4, Italy 0

- A lack of trust

- Technology and the Scottish courts

- For supplement read tax - an update

- Eyes on the ball

- Don't leave gaps in regulation

- Keeping company

- Fighting the bullies

- The university of life

- A lack of trust (1)

- With these few words...

- Tell it like it is

- All that sparkles ain't gold

- PDF is the standard

- The paper monster

- Safeguarding fair trial

- New law, new problems

- Raising the stakes

- Mark the pre-proof

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- It takes two to tango

- Land attachment and suspensive missives

- PSG's suite moves