Guiding hand

Proposals about sentencing guidelines have to be taken seriously – in case they are implemented. After all, no one thought that we would get ASBOs.

The idea of a consistent level of sentence is a superficially attractive one. But only superficially. It may be unachievable (there is no such thing as an “ideal” sentence), and it is almost certainly unattainable. If it were not so, it would be as well to construct a grid, possibly of stiff cardboard with moving parts, which could be handed to an accused in the dock so that they might line up the appropriate co-ordinates and suggest to the court what their sentence should be.

The essential basis,

First, if there are to be guidelines, what underlying philosophy do they seek to put into force? It is essential that this be established, but the present situation is far from clear. On the one hand we have the Kantian model which basically is that to do other than treat each offender as an individual, without reference to others, is immoral. Each person should get their own deserts and no one else’s. On the other hand, the Benthamite utilitarian philosophy would endorse any sentence which would, regardless of its effect on the individual, have the general overall effect of improving the state of society. On this view, taken to an extreme, the death sentence for someone who didn’t actually commit the offence in question is justifiable. These are not easy matters and it may be that some sort of Hegelian synthesis has been achieved, unknown to us. But before guidelines are introduced, we are entitled to be told the underlying, and therefore essential, philosophy. Truisms about making society safer, making everyone responsible for the consequences of their own actions and restoring public confidence in the criminal justice system in the 21st century are in this connection insufficient.

Identical treatment?

Once we have our underlying philosophy in place, what next? Is uniformity necessarily a good idea? Should an offence committed in one part of Scotland attract the same penalty as in another? One example: if a driver in a remote part of the country with no transport services is disqualified for a year, is he thought to suffer the same penalty as someone who lives in a town with buses, trains and taxis? This is the way that apparent uniformity may cloak gross inequality. What, too, is to be done about that other geographical difficulty, prevalence? Is stealing sheep in Glasgow better or worse than stealing one in Berwickshire? It certainly cannot be the same.

Another drawback which certainly might be of concern here is that accused persons too will learn about guidelines. “Steal a cashmere jumper? Why not? At worst it will be a £100 fine. Quite cost effective if you’re only caught every seventh or eighth time.”

A need to correct?

Next, what is the truth about the belief that there are soft and hard judges? As statistics do not reveal what is going on, the evidence must, of necessity, be anecdotal. While this may lead to relative accuracy, it is also the case that a judge’s reputation may well be quite different from the severity of the sentences actually passed. Of course there are anomalies and these are corrected by the appeal court, which does regularly reduce sentences thought to be too severe in summary cases. As sentences in summary cases which are thought not to be sufficiently severe are not normally appealed, it would accordingly appear that the hidden purpose of guidelines must be to achieve more severe sentences. This may be a worthy objective, but I think that we should be told. In any case it has always been part of the judge’s role, on occasion, to exercise a degree of clemency. Clearly there may be a risk in so doing, but people take risks even if guidelines do not.

The factual matrix

Assuming for the moment however that we decide that uniformity is desirable, do we then consider that it is achievable? In order to examine this we have to look at what happens just now. In each decision made by a sentencer a certain number of things have to be factored in. Some things are specific, like certain cases or, effectively, to some offenders. Secondly, there has to be an awareness on the part of the sentencer of certain general matters such as the existence of breach of trust, known vulnerability of victim, local prevalence of a particular offence, public awareness of the seriousness of the offence (for example drink driving during the festive season), general circumstances (for example making bomb threats when there has been a recent explosion) and so on.

Turning to particular aspects of an offence, it will have to be considered whether the offence is a common one, whether it has caused general harm to the community rather than particular harm to an individual (police assault being an example of an offence which does both), whether it is a new type of offence which should speedily be discouraged or whether Parliament has stipulated a particular penalty as maximum or minimum. In this connection of course the interaction between Parliament increasing the potential penalties for a crime and the court’s actual sentencing is a difficult and to an extent controversial one, but it should not be assumed that the judiciary is the effective arm of government policy.

The offender and the victim

The sentencer may also have to take into consideration the attitude of the victim as regards forgiveness or otherwise of the offender, the consequences to the victim, and what such victims may require of the criminal process. (One remembers, for example, the complainer from a few years ago who famously was interested above all not in seeing the perpetrators of a serious assault go unpunished but of discovering why they had chosen to do this and to do it to him.)

And then there is the accused. Criminal record, employment prospects, attitude to the offence, particular problems with drugs, or alcohol, likelihood of reoffending, family and other responsibilities, health, financial problems: all these and more have to be factored in, if not given effect in a particular case. There is also something for which guidelines do not readily provide, and which may be of particular interest to solicitors, namely the fact that pleas in mitigation do, on occasion, bring to the attention of the court material matters that are in the context not entirely expected.

Available disposals

Next, the sentencer has to consider what resources are available in the circumstances. Drug treatment and testing orders have been a success, but there may be other as yet unknown remedies that we should know about, or even known ones that we do not have. Of what we do have, we must ask, for example, is there a domestic violence project, a bail hostel, a detoxification programme? Dare we say it, is there an Airborne Initiative?

Sentencing is not a science, it is an art. Not to understand this is to think that perceived problems can be solved by guidelines. If the system has deficiencies these can be addressed, but only if the existing skills of the existing sentencers are improved. It is to be doubted if there are many sentencers regularly in a position to impose imprisonment (and there are not all that many in Scotland; in fact they could all fit in to a not very large room) who for a long time have not wanted two things. The first is more judicial training, the present level being generally regarded as quite inadequate; the second, more, more flexible, and properly resourced alternatives to custody. There is even a case for sentencers supervising and, if necessary, adjusting their sentences during their currency.

A question of trust

It is some years now since the distinguished criminologist David Thomas, contrasting the Scottish experience with the English, expressed the view in the clearest terms that we should have nothing to do with sentencing guidelines. For them to be introduced here would inevitably lead to a supposition that sentencers were not to be trusted to do their job properly, and in particular not to be trusted to do what they wanted. The constitutional implications of this should not have to be spelled out.

THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME?

In its final report, “Consistency in Sentencing”, published in September, the Sentencing Commission recommends the provision of two forms of guidance to sentencers: greater use by the appeal court of its power under ss 118(7) and 189(7) of the 1995 Act to issue guideline judgments; and an Advisory Panel on Sentencing in Scotland (“APSS”). Similar to the Sentencing Advisory Panel in England & Wales – but not the Sentencing Guidelines Council, which finalises and promulgates guidelines – the APSS, “comprising a reasonably compact group from across the criminal justice spectrum [and supported by a secretariat]… would… provide material assistance to the Appeal Court” in carrying out its duties.

The APSS would draft guidelines for consideration by the appeal court on general topics relating to sentencing, propose guidelines dealing with particular categories of crimes and offences, and consider how any new statutory powers relating to sentencing should be applied before they come into force. A quorum of three appeal judges should be able to approve the guidelines or remit them for further consideration. Sentencers would come under a statutory duty to have regard to relevant guidelines and to state in open court their reasons for any departure.

The report suggests that sentencing guidelines would have the potential to improve consistency, reduce media criticism, increase predictability and therefore realistic pleas by accused and realistic expectations in victims, and assist decisions whether to appeal, without unduly constraining the discretion of sentencers in individual cases. “Guidelines should simply guide, not direct, and should provide clear and practical advice to sentencers. They should not constrain sentencers in cases where there are good reasons for departing from the range of sentences set out in the guidelines. This is fundamental to maintaining the principle of judicial independence. Guidelines would, however, encourage the giving of reasons for the sentences being imposed and thus improve transparency in sentencing.”

The report records that the senior judges expressed the view that the case for guidelines was “unconvincing”, but that “the lower judiciary might welcome guidelines” – Editor.

In this issue

- Home and away

- The importance of kinship care

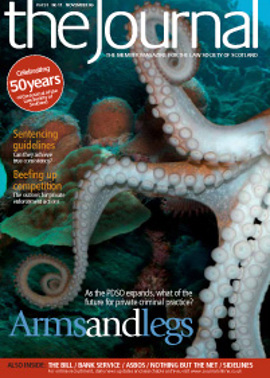

- Growing arms and legs

- Changing its spots?

- Guiding hand

- Trustbusters unite

- Closing the books

- Spam: the managed solution

- Nothing like Nothing but the Net!

- Banking on service

- You want certified?

- Enough is enough

- Provision and prejudice

- Work and families

- Cash trapped

- Man of business

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Sale questionnaire to be tested

- So long, and thanks for all the fizz

- ASBO, the young misfit