Provision and prejudice

The recent divorce case of Orr v Orr, Edinburgh Sheriff Court, 31 July 2006 (Greens Family Law Bulletin, issue 83) has caught the attention of family law practitioners due to the structured application by Sheriff Stephen of the principles contained in s 9 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985.

The Orrs separated in 2005. They had two children aged 11 and nine. Mr Orr was in employment. Mrs Orr had been a senior staff nurse, though had not worked since the birth of the younger child.

At the date of proof the matrimonial home had been sold, and the free proceeds placed on joint deposit pending resolution of the action. Mrs Orr was living in rented accommodation with the children, whose residence was not in dispute.

Accepting imbalance

Mrs Orr, the pursuer, sought a capital payment that would result in her retaining more than half the matrimonial property. She relied on the principles in s 9(1)(b) (economic disadvantage) and (c) (economic burden of caring for the children) of the 1985 Act. She also sought periodical allowance under s 9(1)(d).

In support of a claim under

s 9(1)(c), it was averred that the pursuer would require to purchase suitable accommodation in the catchment area of the school which the children were to attend, and that she would be unable to achieve her full earning potential as her working hours would be restricted by the children’s school hours.

The defender’s position was that there should be either unequal sharing of the matrimonial property in favour of the pursuer to the extent of 52%/48% and no award of periodical allowance or, alternatively, equal sharing of matrimonial property with an appropriate level of periodical allowance for the pursuer.

Sheriff Stephen accepted the pursuer’s arguments for a departure from equal sharing and awarded Mrs Orr 60% of the matrimonial property. She also awarded periodical allowance of £600 per month for a 12 month period.

A less technical approach

The commentary within the judgment on the application of the s 9 principles, and particularly s 9(1)(c), is worthy of note. Sheriff Stephen records that some regard was had by the defender’s agents to the absence of formal pleadings in support of a claim under s 9(1)(c). The sheriff answered this by stating that in this case, and indeed in most matrimonial proceedings, each party was well aware of the other’s circumstances, and that to fail to have regard to s 9(1)(c) in view of the pursuer’s circumstances would be to make a “nonsense of the aim of the legislation”. Followers of strict pleading protocol may disagree with that view.

The sheriff opined that the pursuer did not need to lead detailed evidence on the availability and affordability of housing in the area in question, it being sufficient to aver that accommodation for the pursuer and the children had to be purchased (query, why renting was not considered to be an option). Further, in awarding periodical allowance Sheriff Stephen accepted that it was “reasonable to assume” that the pursuer would require all the capital she was awarded to purchase accommodation, leaving no capital to be invested to generate income.

The decision in Orr is a stark reminder of the wide discretion available to the courts in matrimonial proceedings. Indeed, the sheriff quoted from Lord President Hope in Little v Little 1990 SLT 785 at 787: “the matter is essentially one of discretion, aimed at achieving a fair and practicable result in accordance with common sense”.

The realm of compensation

The Orr case may be seen by some as an indication of a move towards a greater willingness by the courts to “compensate” (usually) wives for financial prejudice that they may suffer in the future as a result of divorce and past sacrifices. Indeed, Orr demonstrates a willingness by the courts to depart quite significantly from equal sharing of matrimonial property that has not been evident in recent case law.

Family law practitioners south of the border have been pondering a similar change in attitude since the House of Lords decisions in Miller and McFarlane. In both cases substantial awards were made to the wives. McFarlane is of particular note. As the wife of a successful accountant Mrs McFarlane had abandoned her own promising career in order to care for the children, thus allowing her husband to further his career. Mrs McFarlane was awarded aliment for herself at the rate of £250,000 per year for life, or until she remarries. It is clear that the House of Lords elected to look well beyond Mrs McFarlane’s needs, and entered the realms of compensating her for relinquishing her career in the interests of her husband and their family.

Here in Scotland, will Orr be simply a minor departure from recent trends, or a precursor of things to come?

Anna McGovern,Morton Fraser Family Law Teame

In this issue

- Home and away

- The importance of kinship care

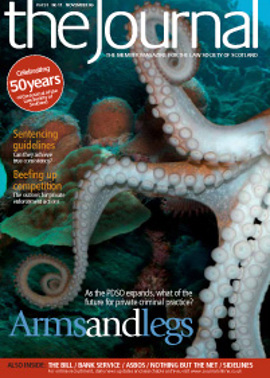

- Growing arms and legs

- Changing its spots?

- Guiding hand

- Trustbusters unite

- Closing the books

- Spam: the managed solution

- Nothing like Nothing but the Net!

- Banking on service

- You want certified?

- Enough is enough

- Provision and prejudice

- Work and families

- Cash trapped

- Man of business

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Sale questionnaire to be tested

- So long, and thanks for all the fizz

- ASBO, the young misfit