Book reviews

Hilary Patrick (et al)

PUBLISHER: TOTTEL

ISBN: 1 84 59 2 062 3

PRICE: £90

Hilary Patrick’s contribution to the development and exposition of mental health law has been outstanding and unique, wholly deserving of the MBE recently conferred on her. She has also made major contributions to the other areas covered by this book. Hitherto her most significant works have been as joint author – Mental Health: A Guide to the Law in Scotland (1990), and The Care Maze (two editions and an update, 1995-98). This work can be seen as a successor to both, and much more; and moreover sees her impressive mastery of a large area of law, and of the art of clear exposition, developed fully as undisputed principal author, though not the only one. Margaret Ross, of the University of Aberdeen, has contributed the wide ranging Part 8, entitled “The Impact of Mental Disorder”, and Lynn Welsh and Irene Henery, both of the Disability Rights Commission, authored Part 9 on discrimination.

This is not a book to compare with any other, because its scope is wider than any other. The remit encompassed in the title is addressed in the fullest way. A full and authoritative exposition of mental health law as it now stands, and a somewhat shorter but fully adequate account of the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000, take up about half the text. These are followed by multi-dimensional coverage of an impressively wide range of topics.

In general, lawyers will find that topics for which substantial other modern coverage is already available receive relatively brief treatment. At an extreme, the major topic (for private client lawyers) of testamentary and inter vivos provision in the context of incapacity and mental disabilities receives little more than passing mention. On the other hand, for many topics without other modern coverage, or at least co-ordinated coverage such as is offered here, one anticipates that this book will be the authoritative starting point for lawyers and non-lawyers alike for some years to come. The book is multi-dimensional not only in addressing the interactions between different areas of law, but also in that as well as addressing the law topic by topic, it also approaches its subject matter from the points of view of people with dementia, people with learning disabilities, refugees and asylum seekers, children and young people, and carers.

Patrick writes in her preface: “While I hope the book will be of use to lawyers, it is not aimed exclusively at them”. It will indeed be valuable for both lawyers and others, and invaluable for many in both categories. The style of writing is clear and helpful, as are features such as brief descriptions of the decisions in cases referred to (those browsing should look, for example, at the footnotes on p 835). It is worth spending some time browsing, to gain a true picture of the scope and layout.

The main criticism is that this is necessary. An encyclopaedic work of this nature demands high standards from the publishers in editing, indexing, preparing tables, and presentation. However we are in an era of diversity not only of publishers, but in their standards. Fortunately this book does not suffer from the serious inadequacies seen recently elsewhere, such as garbled text which cannot have been properly proofread or edited since first draft. On the other hand, the shortcomings evident are significant and unhelpful. Indeed, the publishers appear to have failed to grasp the nature, scope and structure of this book. For example, wills and trusts are addressed, oddly, in chapter 34, “Consumer Rights”, and this is the sole index reference to trusts, but trusts are also addressed in chapters 38 and 42, without cross-referencing. Chapter 33 has two separate main sections headed “Education”, not cross-referenced to each other. Paragraph 26.17, “Duties of solicitor and registration” (relating to financial powers of attorney), simply reads “As for welfare powers”, with no cross-reference; a few pages earlier we are told, wrongly, “chapter 24 dealt with welfare powers”: the cross-reference should have been to paras 25.08 and 25.09. It was surprising that this work, by a solicitor also qualified in England, should have but a single entry in the table of statutes for the (English) Mental Incapacity Act 2005; in fact there are other references in the text, e.g. in para 10.09.

More fundamentally, publicity and even the back cover alternate between describing the book as covering only mental health law, and referring (though inadequately) to the true breadth of its coverage; and there are references both in some of the publisher’s advertising and in the book itself (para 42.01) to its being a second edition, while the copyright notice formalises this confusion by claiming first publication in both 1990 and 2006. It is in fact a successor, and a most worthy one, to the two works mentioned earlier, but – despite these shortcomings – is more than that, and is in its own right a major, indeed encyclopaedic, new contribution to a wide and important area of law.

Adrian D Ward

In this issue

- The shape of your future

- The law and the forum

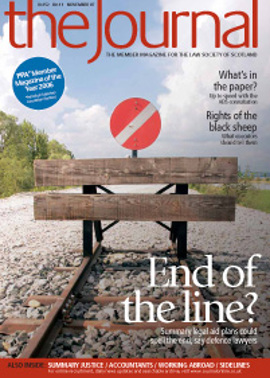

- End of the line?

- Summary justice: the big picture

- Now it's your turn

- Flying south

- Legal rights and the black sheep

- Mediation innovation

- Counting on your CA

- The risk of paper cuts

- Society hits the Net at Murrayfield

- Leading the charge

- Computer says no

- Who, what, where, when, why?

- Getting in on the Act

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Well funded work

- PSG offers an offer