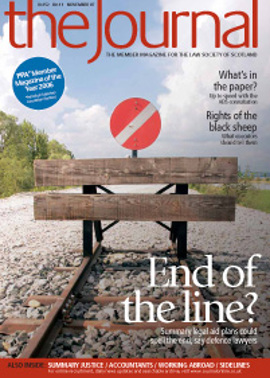

End of the line?

The criminal legal bar in Scotland faces extinction if proposed reforms to the summary criminal legal aid system go ahead.

That’s the stark warning from defence practitioners, who fear the very existence of the country’s independent criminal legal bar is under threat from plans to reform summary criminal legal aid in the wake of far reaching reforms to the summary justice system.

“If the proposals go through unamended in March 2008 it will devastate the profession by October”, predicts former Glasgow Bar Association President Gerry MacMillan.

“The reality is that criminal legal aid practice will become unsustainable. This really will be the death knell. Already firms can’t afford to take on trainees or employ assistants. Civil legal aid practice has been decimated and criminal practice is set to go the same way.”

Disquiet about the proposed reforms goes beyond the self-interest of a squeeze on fees. Under the new disclosure regime, there are concerns that Scottish Legal Aid Board officials could refuse legal aid applications where summary statements provided by the fiscal appear to indicate an open and shut case, or the accused admitted his guilt during a police interview.

Agenda for reform

The reforms are set against a background of changes to the operation of summary criminal justice. Under the new model there will be greater use of direct measures – non-court options, including police fixed penalty notices. Allied to this is the intention that cases come to court more quickly, assisted in part by early disclosure of police statements and fiscals being “ready to discuss the case with the defence… in a meaningful way”.

Tied into that is an agenda for reform of the summary criminal legal aid system which will see a front-loaded system, designed to “facilitate investigation and preparation for the early disposal, where appropriate, of cases”. Preliminary and guilty pleas will be paid under ABWOR (assistance by way of representation), with summary criminal legal aid only available where representation at trial is required. While there is a marginal increase in the core fee for representation at trial, the advice and assistance element currently available to provide initial advice is subsumed into that payment, so the net result is a decrease in the block fee.

Hostile reception

The legal aid proposals are currently the subject of a consultation process which runs until 24 December. As part of that process SLAB, in conjunction with the Scottish Government and Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, has been running a series of information seminars designed to explain the reforms to the profession and receive comments.

Feedback from practitioners at the seminar held in Glasgow was hostile, with accusations that the long term agenda of successive governments and SLAB is the elimination of the independent criminal bar and the rollout of PDSOs around the country.

There was widespread suspicion that the proposals had been formulated without reference to the profession, and scepticism that they were in fact a fait accompli rather than genuine consultation. Current GBA President Gerry Considine compared the process to root and branch reform of the NHS taking place without asking for input from doctors.

Snakes without ladders

The reforms are also predicated on the premise of prompt disclosure of statements by the fiscal and the availability of fiscals able and ready to discuss what matters might be capable of agreement. Anecdotal evidence suggests the promised system of disclosure is not being delivered and it remains difficult to contact fiscals.

What’s certain is that there will be fewer cases going to court and less work for criminal lawyers. With more work being done under ABWOR, there is also the likelihood that fewer people will qualify for legal aid.

GBA secretary David O’Hagan claims that staff will be made redundant, firms will close and criminal practitioners are already talking about changing career. While the current system has “swings and roundabouts”, he cannot envisage any firm being better off under SLAB’s proposals.

Yet equally apocalyptic prophecies were made when fixed fees were introduced and the criminal profession has proved robust enough to withstand change, reinvent itself and re-examine its business models.

This time, however, says Gerry MacMillan, the reality is that “the cuts are so swingeing that nobody has the margins to absorb them”.

Impact on quality

The effect of fixed fees and previous changes to the legal aid regime is being felt most keenly by sole practitioners, according to John Scott, President of the Edinburgh Bar Association.

“People are very gloomy. One criminal lawyer is going to work in New Zealand and another I’m aware of is going to give up. The landscape of legal aid is going to change and what will go to court is going to change; the changes now are the most significant in our lifetimes and there is going to be a big effect on what is being prosecuted and the availability of legal aid. The last legal aid report showed the first increase for a while, and whenever this dance takes place it is not with a view to increasing our income. The experience on the civil legal aid side is a warning; it was also portrayed as an increase, but reality has been far different.”

There are fears that the legal aid package will impact on the quality of representation afforded to accused. This is particularly concerning, says David O’Hagan, at a time when sentencing powers are being increased.

“The way we are paid will affect the way we do the job”, says Scott. “One solicitor will be covering three or four courts rather than two at the moment. Whenever there have been changes there have not been floods of people leaving, and perhaps we have been good at reinventing ourselves; but research has indicated people don’t always prepare as well as they used to, they don’t have the time and staff; there might come a point when we are being asked to adapt to changes and adopt structures where it might not be possible to maintain a good enough quality of representation.”

Gerry Considine predicts people will close offices and start working “from the back of their car”, which could jeopardise the quality of representation on offer.

Generation lost

One further impact of the reforms and the attendant publicity is likely to be a continued shortfall of new solicitors practising in the criminal courts.In 2003 the Journal (May, 16) highlighted fears of a lost generation of criminal practitioners, with firms unable to recruit trainees and students being deterred from embarking on a practice with a gloomy future.

John Scott says there has indeed been a lost generation. “It’s the same faces around the courts, only older and craggier. In Edinburgh there have been a handful of new faces and a couple of trainees, but word has got out and people are not interested in doing criminal legal aid work.

“I went to speak to a class of law students at Edinburgh, and most were not interested in doing legal aid work; they want to do commercial work for financial reasons and at most a dozen said they were interested in criminal practice. Even 15 or 20 years ago there would have been dozens of applications.”

In Glasgow, David O’Hagan says that a decade after starting out he is still one of the younger criminal court practitioners.

To practise or not?

Yet perhaps the demise in numbers coming through the ranks has been a self-fulfilling prophecy. Dire warnings that criminal practice would implode have been heard since fixed fees were introduced, and perhaps the doom-laden predictions made by criminal legal aid practitioners have served to strangle the ambitions of the would-be criminal lawyers of the future.

“Practitioners who make these warnings are only being realistic. The future is not what it was, but we should not be saying don’t come into this area – people are put off enough already”, John Scott observes.

Gerry MacMillan though says it would be “morally wrong” to encourage young practitioners to enter the criminal field in the present climate.

“We’re not being self-serving. We want there to be a future generation to take over and buy us out. But at the moment I would have to advise people not to do legal aid in any shape or form.”

Pre-trial trial?

Aside from concerns about practitioners’ livelihoods, there is distrust over the proposed introduction of a requirement for summary statements to be submitted with legal aid applications.

Now in his 40th year of criminal practice, Edinburgh solicitor George More believes the reforms go to the heart of civil liberties, in particular the notion that a SLAB official will view and consider statements before making an assessment on the merits of the legal aid application. He is also concerned that lawyers are being incentivised to persuade clients to make an early plea, because it will be uneconomical to take a case to trial and risk two or three adjournments.

“It is outrageous. It seems SLAB could refuse legal aid where an accused has made what appears to be an admission of guilt at a police station, or there is other strong evidence pointing to guilt in a summary of the evidence. Often it turns out at trial that the evidence in the statements is not what it appears to be and there is an alternative innocent explanation. Effectively there will be a trial before the trial in the offices of the Scottish Legal Aid Board. In cutting down the cost of legal aid for what is a necessary social service, we are seeing an attack on the rule of law, the independence of the legal profession, the right to a fair trial and the presumption of innocence.”

Gerry Considine echoes these fears, claiming it will effectively see SLAB operating in a “quasi-judicial role” and investigating evidential matters. He argues that it will increase bureaucracy and will require them to employ more legally qualified staff to assess the statements: “SLAB will be relying on summary statements which are one-sided, untested, lacking in detail and often inaccurate.”

Such arguments are unlikely to make a dent on the public or political consciousness. But David O’Hagan says that while the public may be unsympathetic to the impact of cuts in criminal legal aid on practitioners or their clients, people often don’t realise the important barrier a lawyer puts between the victims of crime and the accused.

“More accused will represent themselves and victims will have to face them directly in court. There will be less agreement of evidence. It is acknowledged by sheriffs that for the proper conduct of a case it is better to have solicitors involved.”

Shadow of the PDSO

For many the fear is that there is an underlying agenda to replace independent criminal practice with Public Defence Solicitors Offices around the country.

Gerry Considine insists the fiscal case for PDSOs has never been made. “If they operated as a business they would have been declared bankrupt. I’m not convinced they are as much in favour with the new administration.”

George More describes the concept of a publicly appointed defender as an anathema. “Not only is there no evidence that public defenders save cost, their ethos will always be different from private practice. In a justice system where all prosecutions are taken by the Crown aganst the accused it is necessary on occasions for the defence lawyer who is completely independent of the state to criticise the Crown, to rock the boat and strike out at things that are wrong. These lawyers are often considered to be awkward customers and are unlikely to be found in a public defender system.”

Meaningful consultation

Nevertheless there is hope that the unrest in the profession will be noted and that this will be a genuine consultation. Gerry Considine says the Scottish Government officials were taken aback by the depth of anger at the meetings they had attended, and the widespread resentment that practitioners had been disregarded in formulating proposals. He is optimistic that Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill understands the system and is prepared to listen.

John Scott too has more faith in this consultation process than others he has taken part in. “Since the SNP came into power, a slightly less cynical view has been taken about how responses might be dealt with; we hope that Kenny MacAskill as a solicitor will understand the issues we are raising.

“I am hopeful this might be a proper consultation. For as long as I have been involved in them, consultations have been a waste of time; at times I doubted whether submissions were even read. This time it’s too important to ignore.”

But in Glasgow and Edinburgh there is an awareness that the only time in recent memory that they were seriously listed to was when there was the threat of withdrawal of services in sex offence cases. At present, Scott says it’s not on the agenda, but if it turns out to be a sham consultation, people know that threat may work.

Roger Mackenzie is a solicitor and a former deputy editor of the Journal

LEGAL AID INTO ABWOR – THE UNKINDEST CUT?

Reading the worked examples in the Scottish Legal Aid Board’s consultation paper provides little indication that the proposals are anything other than good news for defence lawyers. The specimen cases set out in appendix 2 suggest that in most instances lawyers will be better off following the reforms.

In a cited case where a client pleads guilty having been given advice and assistance prior to the pleading diet, for example, the Board estimates the average fee currently payable as £120. This would rise to £300 under the new, “front-loaded” ABWOR fee which, it says, “better allows for further investigation, negotiation and representation”.

Even here, however, there is concern among solicitors that ABWOR will be much more difficult to obtain because of the tests, financial and “interests of justice”, that will apply, and may be refused even where work has already been done.

A fuller reading of the body of the document shows the main causes of the profession’s disquiet. According to the Board, only around 15% of cases for which legal aid has been granted proceed to trial, “which means legal aid is used in the majority of cases only to investigate and tender guilty pleas”. The system, it claims, “needs to revert to what was originally intended” – i.e. ABWOR for preliminary and guilty pleas, and summary criminal legal aid for representation at trial.

As a result, ABWOR would expand to include investigation following a continuation without plea, and would be available for a guilty plea irrespective of any application for legal aid.

Explaining that its proposals are intended to facilitate investigation and preparation for early disposal of cases where appropriate, the Board adds that this “will inevitably result in a significant shift in the balance of remuneration away from summary criminal legal aid (other than for cases that need to proceed to trial) to ABWOR for the vast majority of cases that plead”.

The current rules do contain an incentive for solicitors to advise clients to plead not guilty, as an application can then be made for summary criminal legal aid, payable at the fixed fee rate of £500 (£525 in remoter courts) even if there is a subsequent change of plea. However if summary legal aid is restricted to cases that proceed to trial, the going rate, even if a client changes plea at a late stage and after defence preparation for trial, will be the proposed ABWOR payment of £300 – a 40% cut. Hence the uproar and the claims that solicitors will end up encouraging their clients to plead guilty without fully investigating their case.

The Board also wants payment for all criminal advice and assistance to be on a time and line basis, ending the current arrangement for payment of minimum fees, as has already happened with civil cases. “This will direct funding towards the payment of initial advice a solicitor needs to give to progress the case.” And it proposes to bring the capital eligibility limit for summary criminal legal aid (currently £6,879) into line with that for advice and assistance – at present only £1,502.

The Board’s aim to achieve closer scrutiny of the advice actually given is another significant concern for lawyers, as highlighted in the main article, raising issues of independence and the completeness of the information on which the Board will take decisions.

The consultation paper can be accessed from the SLAB home page www.slab.org.uk The deadline for responses is 24 December 2007.

Peter Nicholson

In this issue

- The shape of your future

- The law and the forum

- End of the line?

- Summary justice: the big picture

- Now it's your turn

- Flying south

- Legal rights and the black sheep

- Mediation innovation

- Counting on your CA

- The risk of paper cuts

- Society hits the Net at Murrayfield

- Leading the charge

- Computer says no

- Who, what, where, when, why?

- Getting in on the Act

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Well funded work

- PSG offers an offer