Flying south

One of the most popular destinations for those who want to work abroad is Australia. Many Scottish solicitors have made this move, either on a temporary or permanent basis – it must have been all the Neighbours watching in the 1980s that did it! Australia’s plus points are obvious – an English speaking, vibrant continent which boasts a fantastic climate. For most UK based solicitors, Sydney is the city of choice.

Sydney boasts a booming economy and the legal services market is thriving. As a recruitment consultant with one of the larger consultancies in the city told me, “In terms of the jobs available, the market here in Australia is buoyant. Law firms are keen to source international candidates and I am sure that more of them are now starting to source from Scotland where possible. I know global firms who have Edinburgh offices are keen to speak to people wanting to work in Australia.”

The areas in which those looking to make a move will have most success, unsurprisingly, are the least jurisdiction-specific. As my contact says, “The areas where most international recruitment is happening are in corporate, banking/finance, funds and property, and it’s for the top 20 or 30 law firms. These are the areas which are in really short supply and therefore they are the kinds of roles for which law firms find it easier to obtain visas for international candidates. Visas are generally sponsorship visas, which again mostly are used by larger firms. I think the only other visas you can use to come here are working holiday visas, which really only allow you to do contract work, as you can work for one year but only up to six months for a single employer. In-house opportunities are less readily available, mainly due to the reluctance of companies and banks to offer visas, although a few do.”

Straightforward transfer

One Scottish solicitor who seized the opportunity to use her skills in Sydney was Joanna Moore, a banking solicitor who previously worked at Maclay Murray & Spens. Jo moved to Sydney in January 2006 and has just recently returned to the UK. She worked as a senior associate in the banking and finance department at Freehills, one of Australia’s biggest firms, “advising borrowers and lenders on a wide variety of bilateral and syndicated acquisition/leveraged finance, general corporate finance, property finance and project finance transactions”.

Jo sums up the professional experience as an extremely rewarding one, having found that she was well able to utilise her previous banking experience. “There are a lot of similarities as far as the law is concerned, especially in an area like banking. There are technical differences but it does not take long to get to grips with those.”

What aspects did she find challenging, if any? Jo feels that “the biggest challenge faced by a UK lawyer working in Australia is educating your employer in relation to what qualification level you are at and ensuring that you are treated at an equivalent level in Australia. In Australia they do not have a two year traineeship and some firms will disregard this, or disregard a year of this, when they look at your level of qualification unless you are able to convince them otherwise.”

Overall, Jo cannot speak highly enough of her time in Australia. “I loved it and I would highly recommend it to anyone who is thinking about it. Working in a different market has been very good experience, and although it has been hard work, the lifestyle that you can enjoy in Australia outside work has more than made up for that.”

For those in a similar field, Jo feels that securing employment in Australia would not be a problem. “I personally found the recruitment process surprisingly easy. From what I saw, firms in Australia are desperate for lawyers in areas like banking to fill the gaps left by Australian lawyers who move to the UK to work for a few years. If you secure a job with an Australian firm, they will organise your visa for you and help you with relocation.”

Openings for others

What about those working in potentially less-transferable fields? As Lynne Timmins’ experience shows, it is not impossible to make the move down under if you don’t work in the corporate field. Lynne, an employment solicitor, moved to Sydney from Edinburgh, working there from October 2004 to February 2007. Despite the fact that employment law falls more naturally under the practice heading of “litigation”, Lynne was able to secure a position with a mid-size commercial firm based in Sydney. Lynne acknowledges that it can be more challenging; however, as she says, “it is possible and there are opportunities there for Scottish solicitors”. As for the practicalities, Lynne “applied through some Australian recruiters to start with and then ultimately got the job through a professional contact”.

Like Joanna Moore, Lynne and her husband Michael, an accountant, made the move to Australia to enjoy a new experience and way of life. As Lynne says, “Having grown up and worked in Edinburgh, we wanted to experience living in a different country, enjoy some nice weather and see what it’s like to work in a different jurisdiction. It was really interesting to see how they deal with legal issues in another country.”

I am interested to know how useful did she find her Scottish legal experience? “Although employment law is different in Australia (i.e. the wording of statutes and the leading cases are different), the general concepts are the same – unfair dismissal, discrimination, breach of contract and so on. Also, New South Wales law is based in English law and so the general principles are not too different. As for the challenges – I would say that it is mainly getting used to a new jurisdiction, and also having to resist the temptation of saying to people, ‘In Scotland, we would do such and such.’ On a really practical note, actually getting colleagues and clients to understand my accent was sometimes a challenge!”

Experience first

There may be people reading this who are considering such a move, and who could blame them as we find ourselves in the sun-starved month of November? Lynne recommends that those weighing up whether to make a similar move, consider waiting until they have some experience behind them. “In my opinion it’s best not to make the move too early in your career – get a couple of years of experience under your belt first. Most recruiters will tell you this and it seems to help with selling yourself too. If you are planning to move to Australia longer term and get admitted over there, it would be a good idea to become qualified in English law first (as then you have to do fewer exams in New South Wales – I am not sure what the requirements are like for the other states and territories).” My contact in Sydney confirmed this advice, indicating that “the firms are mainly keen to speak to candidates around the 2-10 year qualified mark from respected and leading firms in Scotland”.

Overall, Lynne highly recommends the experience. “I really enjoyed my time in Sydney – it was a fantastic thing to do. One thing though – if you live in Sydney, make sure you live by the beach! It feels a bit like you’re on holiday when you get home from work and can go for a swim or a walk up the coast.”

KIWIS SCORE A CONVERSION

For Patrick McCann, New Zealand was the country that caught his imagination. Here he describes the hoops he had to jump through to qualify there

“Why contemplate a move to New Zealand? Why contemplate moving at all?”, are questions I have been asked frequently since I started studying to enrol as a solicitor on the other side of the world. I am afraid I have no startling personal insight or philosophical treatise prepared in answer. Either the thought of doing something like this appeals to you, or it does not. Call it a gut feeling. Of course, it would help if you could go to New Zealand and experience the country for yourself, first hand. But imagine, if you will, the north west coast of Scotland, in all its grandeur and beauty, only without the midges and the rain. And the cold. That’s all I’m saying.

The admission of solicitors in New Zealand is administered by the New Zealand Council of Legal Education. There is a minimum requirement for all overseas practitioners, no matter who you are or how long you have practised. This minimum requirement is six, 90 minute, closed book exams. The exam subjects are: the New Zealand legal system; criminal law; property and land law; tort; contract; and equity, wills and trusts.

Depending on when you graduated, the NZCLE may make additional requirements. My own degree being of some antiquity, there was a perceived lack of emphasis on judicial review and administrative law. Consequently, I found myself being lumbered (did I say lumbered? I mean challenged) with the additional requirement of attending university and studying and being examined in judicial review and administrative law, in addition to the six standard exams.

On application, the Council will supply a syllabus which sets out the minimum number of cases, Acts of Parliament, texts and articles on which a student can expect to be examined. At this point it begins to dawn on one that this is going to be a mammoth task that will require maximum commitment. For example, the syllabus for equity, wills and trusts alone contains 85 cases, 11 Acts of Parliament and reference to 10 standard textbooks. Of these 85 cases, five are of English origin and may be familiar to practitioners with experience of equity, wills and trusts. All of the remaining case law, legislation and reading material is 100% pure Kiwi.

Browsing on the internet for some much needed assistance, I encountered the Auckland District Law Society and the Auckland University bookshop. For modest consideration, the ADLS will supply bound volumes of the case law for each subject. There are 10 in total. Auckland University bookshop offers for sale all of the standard texts, and has an online facility that provides delivery within about one week of order. Naturally, I availed myself of its services and was thereafter all set for no small measure of hard graft, in preparation for the NZCLE exams.

The exams are held over two consecutive days, in February and July of each year. The student nominates a domestic university of his or her choice to administer the examination process and thereafter the Council communicates directly with the university. The examinations may be sat, and re-sat, as often as one likes, as long as all are passed within a five year period.

I opted to sit three subjects in February and three in July, with the university exam in the normal course of the academic year, in May. In addition to the hours spent burning the midnight oil, I granted myself three weeks’ study leave immediately prior to each set of exams. This, I hoped, would be sufficient time to mould all the information into some sort of mental order, ready for regurgitation onto an exam paper.

Finding myself in a hotel room the night before each exam, and then alone with an invigilator answering questions about the law of a foreign country, was a surreal experience. However, the countless hours in the library paid off and I managed to scrape a pass in one or two exams and actually do better than expected in the rest. In retrospect, the opportunity simply to sit and study law was an unexpectedly enjoyable experience. Two of the myriad of cases that I looked at stand out: Fitzgerald v Muldoon, in which the then Prime Minister, the infamous “Piggy” Muldoon, was personally sued for contravening the 1688 Bill of Rights and the rule of law by making unilateral decrees without the ratification of Parliament; and The Congregational Church of Samoa Trust Board v Broadlands, for nothing other than its wonderful name.

That was in July this year. Since then I have travelled to Wellington for an interview at the Crown Law Office. The enrolment process is underway and I hope to be in Wellington again before the year is out to enrol at the High Court there.

A degree, a diploma, 10 years of experience and being younger than 45 will qualify any solicitor for entry to New Zealand as a skilled migrant. With a job offer an application will be assessed within two weeks. Without a job offer, you can expect to wait at least four months.

No particular specialisms are in demand. There is wide scope for trying something completely different. Currently there are opportunities in treaty and international law, human rights, Maori land rights, maritime law and environmental law.

A TRULY INTERNATIONAL WAY OF LIFE

Graeme Keay describes how his legal career has led to him providing an advisory service to governments across the developing world

When we take, as students, our first tentative steps towards the legal profession, and nervously enter the law library to read 1932 SC (HL) 31 and other didactic works, we all have thoughts on where they will ultimately lead us. The opportunities given by a Scots law qualification are certainly broader today than they have ever been.

This year, some 23 years after I first entered the law library at Old College, I found myself sitting on the banks of the River Nile in southern Sudan relaxing with a Tusker lager from Kenya under the shade of a laden mango tree, dropping its fruit with alarming accuracy on the unwitting, all the while half listening to the cackle of the walkie-talkie in case the security situation had deteriorated and “precautionary measures” were required. This opportunity to relax was a daily occurrence after working with the Ministry of Finance of the Government of Southern Sudan to design, and draft legislation to implement, a tax system to provide a revenue stream to sustain the newly formed autonomous government.

Working with governments in the developing world, through partnerships with donor agencies such as the Department for International Development, is how I now practise law. I took the step several years ago, while in Australia with the region’s largest firm, to establish a consulting company (and specifically not a legal practice) to concentrate full time on providing a range of services which were proving to be needed as part of international development projects. The door which first opened up the opportunity was an approach I made to the Government of the Fiji Islands in 1990. This in turn led to relationships being developed with the World Bank and the Foreign Investment Advisory Service on projects in East Asia and the Pacific. It became clear that there was a scarcity of legal services in the area of development projects.

What has resulted has been an amazingly diverse set of experiences. Working in Cambodia to develop a new investment law, engaging the Australian DPP to deliver to prosecutors in Oman a training course on anti-money laundering laws, ensuring Lebanon’s customs procedures were compliant with WTO accession obligations, and designing a replacement for colonial revenue laws in Uganda, could not be more different from each other.

Each country has its challenges and its attractions. Conducting workshops with simultaneous translation between speaker and participants has been a challenge. Drafting legislation for a country where the indigenous language knows no capital letters or punctuation, and relies on descriptive narrative rather than precise wording in order to convey even imperative instructions, has been demanding. Social norms vary widely, but I have found that a canny Scottish approach to working relationships is respected worldwide.

I am often asked about how my career impacts on the family. For us, it has meant that we have become truly international, with family in Scotland and Australia, three nationalities and seven passports between us at the last count, and friends in many potential holiday destinations! The children are educated in international schools with the International Baccalaureate programme, which is recognised worldwide for its internationalism, pedagogy and vigour. My consulting has provided opportunities for us to savour cultures in a way that a short holiday could never do.

As for the future, I will be based in central Europe for a few years and will continue the consultancy. I expect to do much travelling in the years to come – there is no doubt that there is a lack of qualified and experienced specialists who are willing to work in diverse environments.

For those who are countenancing what a Scots law degree will bring, I would say that it will reward you many times over – if you are prepared to seize the opportunity it presents.

Graeme Keay is qualified as a solicitor in Scotland and Queensland (Australia) and a barrister and solicitor in the Fiji Islands. He is the director of Legislative Solutions Pty Ltd (www.legisol.com). He is currently based in Gaborone, Botswana as lead adviser on an EU project to establish a new revenue agency.

In this issue

- The shape of your future

- The law and the forum

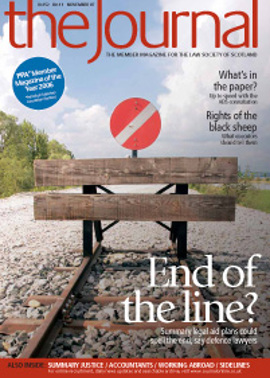

- End of the line?

- Summary justice: the big picture

- Now it's your turn

- Flying south

- Legal rights and the black sheep

- Mediation innovation

- Counting on your CA

- The risk of paper cuts

- Society hits the Net at Murrayfield

- Leading the charge

- Computer says no

- Who, what, where, when, why?

- Getting in on the Act

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Well funded work

- PSG offers an offer