Leading the charge

Sist pending other litigation

In Coleman v Clydesdale Bank 2007 GWD 28-484, an action for recovery of bank charges, Sheriff Pyle refused to sist the cause pending the decision in an English litigation at the instance of the Office of Fair Trading. It was argued in favour of the motion to sist that there was significant overlap between that litigation and the instant case. The issues were similar, the relevant regulations were UK wide, and the common law was the same. Certainty would result from there being only one decision, and failure to sist would result in a significant burden on the courts given the numbers of litigations being pursued.

Sheriff Pyle observed that the onus lay on the party seeking a sist to establish grounds for granting the motion, and sisting an action in such circumstances normally only took place if the record had closed. Any English decision was not binding, but only persuasive. There was no need for a sheriff and crucially the Court of Session to follow the decision reached in England. The issues in the English litigation had not been finalised and accordingly any similarities between the actions might reduce. Sheriff Pyle did not consider any administrative burden to be a relevant issue. That was not a concern of litigants. In any event, any burden was more likely to be theoretical as opposed to real. Further, the number of cases raised against the defenders was not at such a level that to refuse to grant the motion would place an intolerable burden on them.

Recovery of documents

In Thomson v Bank of Scotland 2007 GWD 32-546 the pursuer in an action for recovery of bank charges sought approval of a specification of documents, and commission and diligence for their recovery. Certain calls of the specification were opposed. Sheriff Pyle upheld the opposition and observed that a fishing diligence can be refused when, as in this instance, it involved too wide a search among all the papers of a haver. In this instance, the search could take upwards of 10 weeks and involve the spending of considerable resources to retrieve the documents in the defenders’ hands.

Late amendment

In McGhee v Diageo plc [2007] CSIH 68; 2007 GWD 29-503 the Inner House allowed an appeal against the refusal to receive a minute of amendment three weeks before a four day proof. The amendment introduced a further aspect to the pursuer’s claim for solatium. The Inner House considered that the prejudice suffered by the pursuer in the event of his being unable to include this aspect to his claim far outweighed the prejudice the defenders would suffer as a result of the delay and the potential liability for a greater claim. In relation to the latter point, their Lordships considered in fact that this should not be considered as prejudice. Rather, the amendment was simply the means whereby the real issue of controversy was focused. Awards of expenses would provide sufficient compensation even in circumstances in which the pursuer was an assisted person, as liability had been admitted and accordingly any award of expenses could be set off against any award made in favour of the pursuer.

Inordinate and inexcusable delay

The first attempt to utilise the Inner House decision in Tonner v Reiach and Hall (July article) resulted in Lady Paton refusing the application in Smith v Golar-Nor Offshore A/S [2007] CSOH 161. The accident causing the injury occurred in 1997 and the action was raised in 1999. After legal aid was granted in 2000 the action seems to have proceeded without any particular delay until September 2003. From then until November 2006 there was no contact by the pursuer’s agents with the defenders’ agents. However, during that period the pursuer’s agents were seeking further medical advice and information and sought sanction from SLAB to instruct a further medical expert. Thereafter a consultation with counsel took place, albeit it was delayed as a result of the pursuer’s offshore commitments. Lady Paton considered that any delay, if it was inordinate, was excusable. This was not a litigation in which the pursuer or his advisers had been idle during the three year hiatus. Further, the defenders had not suffered unfairness. They had been able to investigate the incident fully.

Whilst any such application will no doubt be determined on its own facts, I suspect that provided the pursuer can show that steps were still being taken on his/her behalf in potential furtherance of the litigation, it may be difficult for the defenders to succeed in having the action brought to an end.

Family actions

In Taylor v Taylor, Edinburgh Sheriff Court, 24 September 2007, decree of divorce had been granted in absence and thereafter extracted. The defender sought to appeal out of time. The writ appeared to have been ex facie validly served and accordingly decree had been obtained in good faith. As a result Sheriff Principal Bowen noted that the Inner House decision in Alloa Brewery Co Ltd v Parker 1991 SCLR 70 determined the issue and the defender’s application had to be refused. In addition there was no provision for reponing in family actions. The only method to bring decisions in such actions under review was appeal. An appeal could only proceed on recognised grounds for appeal and not considerations which would apply when a decree in absence was reponed. Thus the application also had to be refused on that basis.

In K v S, Kirkcaldy Sheriff Court, 6 September 2007, Sheriff Holligan noted that the terms of s 4 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006 purported to extend jurisdiction in actions of nullity of marriage to the sheriff court. This was sought to be achieved by the amendment of s 5(1) of the Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1907. However the legislation was silent regarding s 7(3A) of the Domicile and Matrimonial Proceedings Act 1973, which dealt with the jurisdiction of the Court of Session in such actions. Section 8 of that statute dealt with the jurisdiction of the sheriff court but was silent as to actions of nullity. Sheriff Holligan accordingly considered that there were questions as to whether the sheriff court indeed had the jurisdiction purportedly given in s 4, particularly if the defender was not domiciled within the jurisdiction of the sheriff court.

Diligence against state benefits

In North Lanarkshire Council v Crossan 2007 GWD 32-543, the common debtor argued that the arrestment which was the catalyst for an action of furthcoming was incompetent, as the payments into the account arrested were state benefits paid to provide a minimum level of subsistence and were thus alimentary in nature. Further, as these were the only payments made into the account they were identifiable. Legislation made it clear that such benefits were exempt from attachment. Arrestment was a judicial assignation and assignation of such benefits was prohibited by statute. (As an aside, a party recently made a similar submission before me regarding bank charges operating upon an account into which such benefits alone were paid.)

Sheriff Galbraith decided that although the funds were alimentary in nature, they could lose that character, as they did when they were deposited in an account and the common debtor chose not to use them. The relationship between bank and customer was one of creditor/debtor and the funds once deposited in the bank were no longer protected. The intention of Parliament was only to protect the funds when still in the hands of the payer. Decree of furthcoming was accordingly granted. As a postscript and no doubt of no interest, I took the same view in the action to which I have referred!

Identity in sequestration

Petitioners had proceeded to sequestrate H B Engineering, the trade name of an individual. As a result of difficulties encountered, the Accountant in Bankruptcy then raised an action for declarator. In Accountant in Bankruptcy v Butler 2007 GWD 32-542 Sheriff Principal Kerr reversed an interlocutor allowing a proof. A trading name was not a legal entity and a petition for sequestration required to run in the name of a legal persona. OCR, rule 5.7(1) did not extend to sequestration. Sequestration was not a form of diligence but rather something above and beyond, and required an even greater degree of precision in the identity of the prospective bankrupt. To decide otherwise might result in trade creditors of an individual being aware that that person was bankrupt because they were aware of the trading name, but not the domestic creditors who were unaware of that name. Accordingly the sequestration was incompetent and the award a nullity. As a result, the problems with the award could not be cured by the action for declarator.

The sheriff principal also remarked disapprovingly about the apparent use of sequestration and liquidation, with the accompanying appointment of an interim trustee and provisional liquidator respectively, solely as a means to recover the petitioning creditor’s debt, the petition being dismissed once that debt is paid.

The usual caveat applies.

In this issue

- The shape of your future

- The law and the forum

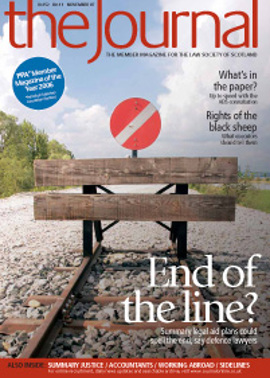

- End of the line?

- Summary justice: the big picture

- Now it's your turn

- Flying south

- Legal rights and the black sheep

- Mediation innovation

- Counting on your CA

- The risk of paper cuts

- Society hits the Net at Murrayfield

- Leading the charge

- Computer says no

- Who, what, where, when, why?

- Getting in on the Act

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Well funded work

- PSG offers an offer