Who, what, where, when, why?

Handling redundancies has always been tricky for employers. It is essential to ensure that employees are consulted. However, as the need for job losses often arises for economic reasons, it is important to complete the process as quickly and efficiently as possible. Balancing this against the need to comply with the statutory procedures allows employers little room for error if they are to avoid unfair dismissal claims or the making of protective awards.

The statutory dismissal and disciplinary procedures (DDPs) do not apply to collective redundancies, i.e. 20 or more proposed dismissals within 90 days, where the duty to inform and consult employee representatives under s 188 of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 applies. However, in individual redundancy situations – to which the DDPs do apply – it has been difficult to know exactly what constitutes sufficient information to satisfy step two of the DDPs, which requires the employer to provide the “basis” for a proposed dismissal. Though not set out expressly in the Employment Act 2002 or the associated SI 2004/752, the EAT has offered guidance in Alexander v Bridgen Enterprises, UKEAT/107/06.

Basis for dismissal

The EAT stated that in a redundancy context, an employer seeking to comply with the DDPs should provide information both as to why there is considered to be a redundancy situation and as to why the particular employee has been selected. The employer must therefore notify the employee of both the selection criteria and the assessment of the employee’s performance under such criteria. Only then will the employee have a full opportunity to make representations about whether the criteria are justified and appropriate, and whether their own scores are fair – although another EAT decision, Davies v Farnborough College of Technology, UKEAT/0137/07/LA, makes it clear that failure to provide actual scores will not always be fatal to an employer’s chances of defending a claim.

The EAT in Alexander also considered whether the employer should provide a break point to the employee, i.e. the minimum standard which must be attained to remain in employment. Whilst it decided that this would be too stringent a duty to impose, it might be suggested that, where possible, this break point also be provided to assist the employee understand why they have been selected.

Whilst, at first glance, Alexander appears to place onerous requirements on employers, the reasoning is clear: complete information provides the employee with the greatest opportunity of responding in full; this allows greater understanding of the situation and should result in any gripes about the process being dealt with in-house, avoiding a costly and time-consuming trip to the employment tribunal – the principles at the very heart of the statutory dispute resolution procedures.

Section 188: reasons for redundancy

Talking of such costly and time-consuming trips, I turn to the recent case of UK Coal Mining Ltd v National Union of Mineworkers (UKEAT/0397/06/RN and UKEAT/0141/07/RN), in which the maximum protective award of 90 days’ pay was made in respect of more than 100 employees as a result of failures in the collective consultation process.

For many years there had been concerns about the financial viability of the colliery in question. Part of it was then flooded and the employer owner informed the unions and the DTI that there would need to be a closure for “safety reasons”. The tribunal found this assertion to be “blatantly untrue”, the real reason being the financial difficulties which had beset the colliery. It then found various flaws in the consultation process (hence the protective award), but also went on to hold that there was no obligation to consult on the decision to close the pit, applying obiter comments by Lord Glidewell in R v Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, ex p Vardy [1993] IRLR 104 to the effect that consultation need not take place as to the reasons for redundancy.

On appeal, the EAT held that these comments no longer hold good in light of changes to s 188 of TULR(C)A as long ago as 1995, made to bring UK law closer into line with Council Directive 75/129/EEC (now replaced by Directive 98/59/EC). As a result, s 188 requires employers to consult on means of avoiding dismissals, as opposed to the previous obligation to simply consult about the dismissals themselves. The EAT has held that in order to allow full consultation on avoiding redundancies during a closure, employees must be given access to the business reasons behind the closure, and the comments in Vardy are no longer good law.

The new case law arguably just provides further clarification of duties already contained in the legislation. Nevertheless, as the consequences of non-compliance are significantly more onerous than the requirements themselves, it is advisable to ensure that all employer clients are up to date with the key points.

Jane Fraser, Head of Employment, Pensions and Benefits, Maclay Murray & Spens

In this issue

- The shape of your future

- The law and the forum

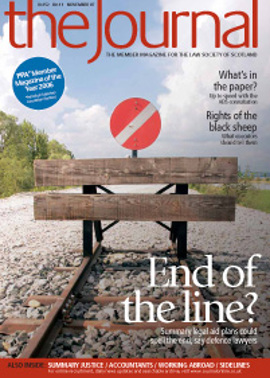

- End of the line?

- Summary justice: the big picture

- Now it's your turn

- Flying south

- Legal rights and the black sheep

- Mediation innovation

- Counting on your CA

- The risk of paper cuts

- Society hits the Net at Murrayfield

- Leading the charge

- Computer says no

- Who, what, where, when, why?

- Getting in on the Act

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- Well funded work

- PSG offers an offer