A backward advance

The government proposals for “Strengthening Judicial Independence in a Modern Scotland” are wide ranging, but I would like in this article to focus on “conduct” of judges (also referred to as “discipline”). “Judge” of course includes “sheriff”.

My starting point is the independence of the judiciary, which has been part of the Scottish constitution by statute since 1689, and probably at common law from the foundation of the Court of Session in 1532.

Under the existing arrangements, if a judge goes wrong, the situation is not without remedy. Where the judge makes an apparently wrong decision in a civil or in a criminal case, the decision can be appealed in the appropriate way.

If a judge is thought to have become unfit for office (“by reason of inability, neglect of duty or misbehaviour”), the present system of dealing with that situation has worked well since Acts of 1877 and 1898 in the case of sheriffs. And the application of a similar system to the judges of the Supreme Court came about just recently: Scotland Act 1998, s 95(6) to (11).

This means that judges cannot be removed without good cause, and they should not be penalised for their decisions. These, like the freedom of the press, should not be interfered with without good reasons.

If a judge is not unfit for office, he must be fit for office. The present proposals envisage the creation of an unwieldy apparatus to deal with some amorphous thing – called indiscipline or misconduct – something in between fitness and unfitness.

A serious problem?

Each year, judges make hundreds of thousands of unremarkable decisions at all stages of criminal and civil cases. The present proposals do not give any figure for the incidence in the course of these decisions of unacceptable behaviour; and surely the incidence of cases where a judge’s conduct falls short of conduct which would raise a question of fitness for office, must be minute. And indeed on the showing of both consultative documents themselves, that incidence would be small. Yet, what is proposed is an elaborate structure for dealing with a problem of unproven gravity and unproven frequency.

Any attempt to define true misconduct immediately raises a host of difficulties.

These difficulties would be apparent whether the conduct touches on the judicial function, such as delay in issuing judgments (which was canvassed in the earlier government document), or relates to the judge’s personal conduct in court, such as rudeness.Since the evil is not widespread, there is a danger that the very existence of such a procedure would encourage a barrage of allegations of inappropriate behaviour from any source, and would create a perception of “widespread failings within the judiciary”.

Loss of judicial time

What if the judge disputes the allegation, say of delay in issuing judgment? It may be that the complaint is erroneous, and that the judge had already issued the judgment. Or it may be that the judgment has been delayed because it is necessarily long and complex, because it followed a long and complex proof, or because the judge has been assigned to other more urgent business (such as an adoption proof), or because the judge was ill.

Also, during the currency of the inquiry, the courts would be deprived of the services of both the judged and the judgers.

Let us further assume that the judge has been found to have been guilty of some misconduct. Then, the judge may appeal against that decision, thus causing further significant delay.

Such delay is not fanciful: it has happened in a case involving the fitness of a judge. In 1992 the judge took a judicial review against the decision which found that he was unfit. The case was finally heard by five judges in the House of Lords in 1998: see 1995 SLT 895, 1996 SC 271, 1998 SC(HL) 81, and the case was heard over six years by a total of nine judges (or 11, if one includes the two judges who held that the judge was unfit).

Now it is suggested that there will be the involvement of the Lord President who may appoint other members of the judiciary to investigate any complaint, with a possible review by two other judges.

Clearly, on the other hand, in an extreme case, if a judge does persistently fail to issue judgments without cause, that may indicate that the judge is unfit, by reason of “neglect of duty”, or “incapacity”. Then, that unfitness can be established by using the statutory procedure which presently exists.

Thus, if the “inappropriate behaviour” is trivial, it is not worthy of an inquiry; if the conduct is indicative of unfitness, the existing procedure would meet the situation.

Transparent system

The present system for removing an unfit judge provides for the involvement of all three branches of government, but in a system of checks and balances. The judiciary (the Lord President and Lord Justice Clerk) may make an inquiry into the fitness of the judge. The executive (the First Minister or Scottish Ministers) may make the order removing the judge. And the legislature (the Scottish Parliament) may annul the order.

Over the last 40 years (and presumably before then) this simple and elegant system has met all problems that have emerged, apparently without criticism. The result has been, in the cases that have arisen (and there have been very few), that the unfit judges have been removed (two, by my recollection); the fit judges have remained in office (probably not more than 10 examples); and in one or two cases, judges have resigned before any inquiry.

As for openness and transparency, nothing could be more open and more transparent than to have the proceedings available for all to see as a public record, such as Hansard, which has the report of the Lord President and the Lord Justice Clerk finding that the judge was fit or unfit; in the case of an unfit judge, the order of the executive removing the judge; and the debate (if any) in the Parliament on the motion to annul the order.

On the other hand, the proceedings which are now proposed are to be confidential, “except where the Lord President considered that it would be in the interests of the administration of justice for the outcome to be given some publicity”.

But what is misconduct?

The government came to the view, after the original consultation, that there was “general agreement that no attempt should be made to define what might constitute inappropriate conduct”: now they anticipate “that the required standards would be determined by the judiciary and set down in a code of conduct or judicial ethics under the authority of the Lord President or, perhaps, the Judicial Council”.

It is difficult to imagine how anyone, even a future Lord President or a judicial council, would go about the mammoth task of setting down such a “code of conduct or judicial ethics”, especially deciding what the code would include or, more significantly, what it would exclude. In the first place, the framer of the code would have to define “judicial ethics”, and decide, for example, whether “judicial ethics” differs from ordinary ethics.

Presumably the code would have to be exhaustive and precise, because it appears that the proceedings against a judge would be limited to breaches of the code.

The attempt to produce a very model of a “judicial office holder” would be very difficult. A few thoughts may suffice: the code could be limited to judicial conduct in court, such as politeness, dressing appropriately, timekeeping, or prompt issue of judgments; or it could be extended to include misconduct or lack of ethics off the bench, such as intemperate political or religious or racial remarks, or domestic turmoil, or alcoholism, or commission of some petty road traffic offence.

Who might complain?

A fundamental decision will be whether the scheme envisages that anyone off the street could complain about real or imaginary breaches of the code (as with complaints about advertising standards), or that the class of complainers should be limited to those involved in the litigation, or those present in court, or the press or the local faculty.

Whatever the classes of complainers, the Lord President would have to sift the mass of complaints, whether or not they are to be struck out because they are directed at the merits of a judicial decision, or are vexatious, trivial or lacking any supporting evidence. It is not clear whether the offending judge would be heard in this sifting process.

Penalties and purpose

The penalties which are envisaged for misconduct do not extend to docking the judge’s salary. But the disposals which are proposed have an almost arbitrary ring to them, leaving the judge in limbo.

The Lord President would have “a general power to suspend from office any judicial office holder in circumstances where the Lord President was satisfied that such suspension was necessary to maintain public confidence in the judiciary”.

Now, one can understand the Lord President and the Lord Justice Clerk recommending that a judge be suspended pending their investigation into the fitness of the judge (as is competent under the existing procedure), but not (as is suggested here) an actual suspension with nothing pending. It is difficult to imagine what kind of misconduct would justify suspension, and what amount of reformation would warrant lifting the suspension.

Similarly, uncertainty appears in another of the disposals for misconduct: for example, the Lord President would be given power to give the defaulter “a formal warning”. A formal warning of what? Proceedings for removal? Or something else?

Uncertain course

All in all, what are we to make of these proposals? Some phrases spring to mind: do not legislate for admittedly rare birds; and do not mend something that is not broken.

My submission is that the proposals do nothing towards “Strengthening Judicial Independence in a Modern Scotland”, but rather the reverse.

The minister says: “Until we reach decisions on the role of the Lord President in the governance of the Court Service, we cannot take a firm view on the subsequent legislation”, including arrangements for conduct of the judiciary.

Surely, the best course would be not to proceed with subsequent legislation dealing with the conduct of the judiciary.

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

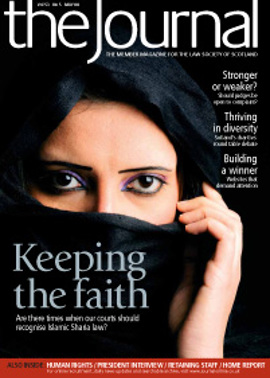

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way