A new framework for Europe

From the beginning of next year the European Union’s legislative and political framework will be governed by the provisions of the new Treaty of Lisbon, the follow-up to the failed Constitutional Treaty of 2004. That is, if all national governments succeed in ratifying the Treaty back at home.

So far so good, as a number of member states have quietly completed their ratification process, including Bulgaria, France, Greece, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. Only Ireland has put the Treaty out to a referendum, as provided for in their constitution, and this is scheduled for 12 June. Seemingly bruised by the referendum experience in 2005, when the constitution was met with a resounding “No”, both France and the Netherlands shied away from putting the new text to a vote. All eyes are now on Ireland, with political commentators, Euro-sceptics, and the other EU nations waiting with bated breath for the outcome.

Ireland caused upset in the EU the last time round with the Nice Treaty in 2001. It was only during a second referendum on this Treaty that voters answered “yes”. Back in the UK, the European Union Amendment Bill has survived the rigorous debates in the House of Commons and is now making its way through the Lords. The Scottish Parliament has no formal role in the ratification proceedings.

Constitution or not?

When negotiations on the new European Union framework began in earnest last year, the rejection of the Constitutional Treaty loomed large. The political mood was one of pragmatism rather than optimism, and this was clear in the outcome. Rather than unveiling a single constitutional document, national leaders signed up to a “Reform Treaty”, one that presented a series of amendments to the individual European Treaties as they have accumulated over the years. With caution the order of the day, all controversial references to a “constitution” disappeared, along with all references to flags, mottos, anthems etc. For the avoidance of doubt, the message from the June 2007 leaders’ summit was: “the constitutional concept, which consisted in repealing all existing Treaties and replacing them by a single text called ‘Constitution’, is abandoned”.

Constitution or not, it is however the framework under which the European Union will function for the foreseeable future. It makes extensive changes to the existing Treaty on the European Union (TEU) and the Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC), and in some instances shifts the balance of power between the EU institutions.

What does this mean for you?

The new Treaty matters to the legal profession, as it will bring about changes both in how EU legislation is proposed and adopted, and also with regard to the rights of individuals and organisations in the EU. A number of specific carve-outs were secured by the UK in relation to criminal justice, police and fundamental rights, which may result in a patchwork of rights and legal obligations around Europe. Practitioners need to be aware that the UK Government can select whether or not to opt in to a specific proposal – for example any future legislative instrument on procedural rights or cross-border recovery of maintenance obligations. Whilst deemed to protect the UK’s national interest, it could result in marginalising the UK and cutting off avenues of legal redress to UK based individuals and businesses.

The role of national parliaments

So far in the life of the EU, there has been no formalised role for national parliaments in the European decision-making process. It has been left to each individual member state to decide how far to involve its national parliament in European lawmaking, and very different practices have arisen. For the first time, the adoption of EU legislation will be subject to prior scrutiny by national parliaments, which will be given the opportunity to challenge proposed legislation if it does not conform to the principle of subsidiarity (i.e. that legislation should be adopted at the appropriate level, which might be national rather than European). If one-third of national parliaments object to a proposal, it is sent back to the Commission for review (a “yellow card”). The Treaty also introduces what has been dubbed an “orange card”: if a majority of national parliaments oppose a Commission proposal, and they have the backing of the Parliament or the Council, then the proposal is abandoned.

Whilst Westminster, particularly the House of Lords, is no doubt gearing up to fulfil this function, the debate on Holyrood’s role in the process is yet to commence in earnest. Although the official wording of the Treaty may suggest the UK Parliament would be the key protagonist, there should be scope for the Scottish Parliament to engage in this enhanced scrutiny process, particularly as key developments in the EU relate to the justice area – one of the devolved competences, where, in practical terms, Scotland has different legislation, procedures and institutions. Better definition of the role of Parliament will also assist in clarifying how the Scottish Government might function in negotiations with UK Government departments on important questions such as whether the UK will opt in to legislation in the criminal justice and civil and family law fields, as there may be differences in view on this on either side of the border. This will all have to be worked out.

These are some of the points that the Society made in evidence submitted to the House of Lords in their inquiry on the Treaty of Lisbon. The Society highlighted the importance of ensuring maximum involvement of devolved administrations in relation to the enhanced role of national parliaments and as regards the opt-in arrangements in the area of freedom, security and justice. The Society argued that traditions and norms of national justice systems should “be treated with care”, and that the principle of subsidiarity should be strictly observed. The Lords drew heavily on this argument when formulating their conclusions, as set out in the report from the Select Committee on European Union “The Treaty of Lisbon: an impact assessment”.

EU justice matters

In order to kick-start the debate on these issues, the Society co-hosted a round table on “EU Justice Matters” with the Scottish Parliament Justice Committee last month in the European Parliament. With Director General for Justice, Freedom and Security Jonathan Faull opening the event, a lively discussion was had with high level panellists, including Members of the European Parliament, members of the House of Lords Select Committee and representatives of the Scottish Government.

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

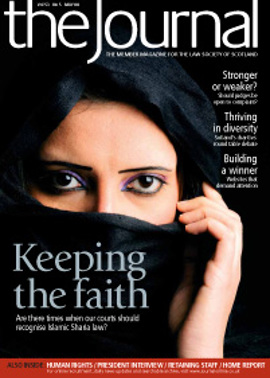

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way