Audience on your side

Rights of audience

In Anderson, Petr [2007] CSOH 110; 2008 SCLR 59 the petitioner was represented by her son, who was a member of Faculty. He, however, represented his mother in a personal as opposed to a professional capacity. The petitioner’s son argued that in circumstances in which a party litigant was unable to appear and the court was so satisfied, there was an inherent right to allow another person, who did not have rights of audience, to represent that party’s interests. A power of attorney had been granted by the petitioner in favour of her son entitling the latter to represent her and appear as a party to that action.

Lord Mackay of Drumadoon refused the application. It was incompetent for an unqualified person to appear on behalf of another. It was not possible to allow a person assisting a party litigant to address the court on behalf of the party litigant. The power of attorney was of no relevance.

A related question arose in Cultural and Educational Development Association of Scotland v Glasgow City Council [2008] CSIH 23; 2008 GWD 10-174. One of the issues was whether a member of a voluntary association could competently sign an initial writ. The other was whether that member could represent the association in court. In deciding the appeal the Inner House determined that such an association, although it might be a grouping of natural persons, was not itself a natural person. Whilst it could sue or be sued in its own name in the sheriff court, it did not follow that it should be treated as a natural person. Accordingly, an association could not initiate proceedings by an initial writ signed by one of its members. The writ was a nullity and the dispensing power had no locus to operate. The initial writ should never have been accepted by the sheriff clerk.

Professional conduct

Still on the issue of conduct of proceedings, in Henry v Rentokil Initial plc [2008] CSIH 24 the Inner House again made comments about the professional obligations incumbent on agents in the conduct of litigation. In this instance an appeal hearing, estimated to last four days, ended midway through the second day. The court observed that the overestimate had resulted in judicial time being wasted and prevented another matter being heard. Agents had duties to the court as well as the litigants. Proper and timeous discharge of such duties was not conditional on instructions from clients.

Evidential matters

In two recently reported decisions, issues relating to civil evidence have arisen. In the first, Advocate General for Scotland v Montgomery [2006] CSOH 123; 2008 SCLR 1, Lady Paton considered that a certificate issued in terms of s 70 of the Taxes Management Act 1970 of the tax charged, due but unpaid, is sufficient evidence on the issue. These certificates were, however, not conclusive. Accordingly the defender was entitled to a proof into the issue of tax liabilities. It was not necessary to reduce such certificates to dispute their accuracy.

In Riddell v Leisure Link Electronic Entertainment Ltd [2008] CSIH 16; 2008 GWD 8-154, evidence had been led at the proof in the form of video evidence purporting to show the pursuer walking relatively normally. The pursuer’s general practitioner had also treated her for a number of years for back pain. The sheriff had awarded damages for back injury sustained in the course of her employment in May 2000. The First Division upheld the sheriff’s assessment of the evidence. He had rationally justified his conclusion as to the credibility and reliability of the pursuer. She had been in the witness box for five days and thus observed for that period. Her general practitioner spoke of her desire to return to work. This was detailed in the medical records. Her husband and son supported the pursuer’s evidence of her disability. Some of the video footage had not been lodged in court, and important aspects of the investigator’s evidence, which related to video footage not lodged, were not put to the pursuer or medical experts who were questioned in cross about some footage actually lodged in court. The sheriff had a proper basis for rejecting the defenders’ challenge to the pursuer’s credibility and reliability. Further, he had rationally explained why he had concluded that the accident had caused the pursuer’s injury in light of the evidence of the medical experts, notwithstanding the prior treatment for back pain. The lessons to be learned by practitioners are self evident.

Summary cause and small claim

In Penman v The Auction Rooms 2008 GWD 10-178 (named in error as the pursuer traded as The Auction Rooms), the dismissal of a summary cause at a continued preliminary diet was appealed. The pursuer sought delivery of an item. The sheriff considered that for the pursuer to succeed he had to prove the defender had been given the item in error. The documentation produced made it clear that this could not be established. The statement of claim and defences, however, seemed to indicate that there was a factual dispute. Sheriff Principal Bowen considered that at the continued preliminary hearing, once the sheriff determined that a negotiated resolution was not possible, he could either assign a proof, or if satisfied that the facts were sufficiently agreed, determine the matter then and there. As the documents undermined the pursuer’s whole case and no explanation could be given for this, the facts were readily ascertainable and thus it was entirely appropriate for the sheriff to determine the issue.

It seems to me that this decision is a practical demonstration of the terms of summary cause rule 8.3(3)(d) working in practice. I suspect that this may not often happen, in part due to the programming of a court being such that the time available to deal with a summary cause at a preliminary hearing in most instances is limited.

It is also worth contrasting the above with the circumstances in Niven v Ryanair Ltd, Aberdeen Sheriff Court, 15 April 2008. In that case, after a minute for recall had been granted and the initial defence was withdrawn, a further defence based on jurisdiction was presented. An appeal against a refusal at first instance to allow the second line of defence to be stated was successful, and the action was dismissed on the basis of no jurisdiction. The fundamental nature of jurisdiction was clearly the basis of the successful appeal.

An interesting aside comes from this decision. Whilst the application for the stated case was lodged timeously, through an oversight it was not accompanied by the appropriate fee. The sheriff clerk did not advise of this omission promptly, which resulted in the fee being paid after the time for lodging the application had expired. The issue was whether the application had been lodged timeously. Did a document have to be accompanied by the fee to be accepted by the sheriff clerk and thus lodged? Sheriff Principal Young did not need to consider the issue as he was not addressed in full and it was a clear case for the exercise of his dispensing power.

The usual caveat applies.

Update

Since the last article Billig v Council of the Law Society of Scotland (January article) has been reported at 2008 SLT 227, AS or B v Murray (July 2007) at 2008 SCLR 19, and Clarke v Fennoscandia Ltd (March article) at 2008 SCLR 142.

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

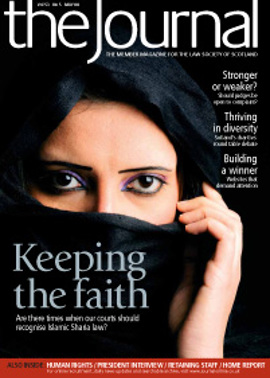

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way