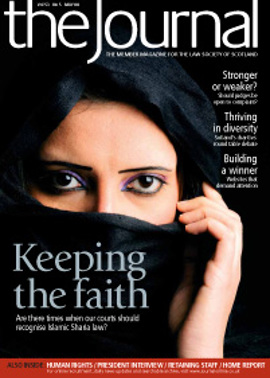

Faith in the law

Dr Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, caused a storm, intentionally or unintentionally, by saying that the incorporation of some aspects of Sharia law into the law of the United Kingdom is “inevitable”. Even assuming that he was referring to English law rather than the law of the UK as a whole, his comments were remarkable enough. But what is Sharia family law?

If Muslims living in Scotland wish to regard the Sharia as their personal law in preference to the general law of Scotland, to what extent should the Scottish courts acknowledge this and give it weight? Is it actually ever proper to take note of the Sharia and its policy in a Scottish family court? Is it proper for Muslims to seek remedies through the Sharia courts within the UK, on analogy with the principles of international private law?

The debate is picking up speed in England. The issues will have to be addressed in Scotland sooner or later. Scotland does not have the huge and coherent Muslim populations found in the large English provincial cities and in specific areas of London. Nevertheless it may be useful to have a look at what some of the Sharia principles actually are.

Differing traditions

Within Sharia law there are different schools of thought. There is one main school for Shi’ite Muslims and four main schools for Sunni Muslims. Because of this there is no universally accepted version of Sharia law, and the following should be taken as a general guide only. The great majority of Muslims within the UK are Sunnis, but it is important to ask which community your client belongs to before seeking expert advice.

I will look first at Muslim divorce, since that is probably the area which is most misunderstood in the west. The allied question of recovery of matrimonial property, including dower, is one which can arise in the context of a Scottish court interpreting the intention of a donor or applying the terms of a pre-nuptial contract. This is an area in which Scots law can be more useful and flexible than the law of England for Muslims intending to divorce.

Divorce: myth and reality

The first myth about Islamic divorce is that it is open only to men. This is not correct at all – it is just that the rules for divorce actions can differ depending on the gender of the applicant.

There are various forms of divorce by a husband, but only one preferred process. This preferred talaq procedure requires the parties to seek reconciliation. It seems that Muslims hit on a form of almost compulsory attempted reconciliation long before CALM and FMS were born.

If a reconciliation fails, the husband pronounces talaq when his wife is in a state of purity, i.e. not menstruating. If she is not in that state of purity, the talaq is not allowed. As soon as the talaq is pronounced (i.e. the words “I divorce you”), the wife immediately enters the period of iddat, which lasts for three menstrual cycles. During this period there is to be no sexual contact between the parties. If there is any such contact the talaq is revoked.

The pronouncement of the talaq may be orally or in writing, but must in any event be done before two adult male witnesses. There is no particular form of words, but they must be clear in intention.

The husband has the option of several other kinds of divorce, some of which are regarded by Islamic jurists as being un-Islamic. The various Islamic schools of legal thought disagree about some aspects of the validity of the different kinds of divorce.

The myth in the west is that the husband can divorce his wife by pronouncing talaq three times in one go. Some parties from the sub-continent sometimes regard this form of divorce as valid, but almost all schools regard this talaq al bidah as unlawful.

There is no doubt that the first option – the talaq under the preferred procedure – is by far the commonest in modern Islam.

Divorce by the wife

The wife may divorce her husband on any one of a number of grounds, such as physical harm, apostasy, and separation without agreement for a period of four months during which no sexual relations have taken place. There is a radical shadow here of s 1(2)(e) of the Divorce (Scotland) Act 1976, as amended by the 2006 Act.

Actually, the Qadi can grant divorce on any cause which he considers justifies it.

As with the approved talaq form of divorce, the wife’s khulah also involves an iddat period of waiting. Once again this lasts for three menstrual cycles or, where appropriate, three lunar months. If the wife is pregnant at a time when she seeks her khulah, the waiting period is until the birth of the child.The mahr (dower)

One area of Islamic family law which has no echo in Scots law is the mahr (pronounced “mahoor”). It is very common in Islam – some jurists say compulsory – that when a couple marry, the groom should give to the bride the mahr – that is, a gift of some value. (The translation as dower or dowry perhaps ignores that “dowry” implies a sum of money settled on the bride by her father to improve her chances of a good match, and given to the husband.) The value should depend on the economic circumstances of the groom and has absolutely nothing to do with those of the bride. Even if the bride is very much wealthier than the groom there is no reciprocal gift. The mahr can be a sum of money, a house, a car, a prayer mat, or even an incorporeal gift such as a promise on the part of the groom that he will learn Arabic. Usually however it involves a gift of intrinsic value, and it should be agreed and witnessed.

There are two forms of mahr – an immediate payment at the point of marriage, or one deferred to a later agreed date or event – and any given marriage may have either or both. The deferred mahr is particularly significant in divorce, because if the husband divorces the wife he must pay her the deferred mahr on divorce no matter the ground of divorce he has selected. If the wife divorces the husband, she must usually waive the deferred mahr and may also be required to repay any mahr she has received. Clearly some wives will be subject to a degree of pressure from their husbands or their husbands’ families to divorce the husband in order that they can save money.

Treatment in the courts

The mahr was considered by the English courts in Shahnaz v Rizwan [1964] 3 WLR 1506. The parties had married in India in 1955 and had agreed a deferred mahr in a written marriage contract. The husband divorced the wife in 1959 and the wife raised an action in England, where both parties then lived, for recovery of £1,400 as the sterling equivalent of the deferred mahr.

Winn J saw the matter as a contractual rather than a matrimonial matter: “while it can in the nature of things only arise in connection with a marriage by Mohammedan law (which is ex hypothesi polygamous), it is not a matrimonial right. It is not a right from the marriage but it is a right in personam, enforceable by the wife or widow against the husband or his heirs”.

The force of this case was largely removed by the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973, which essentially gives the English court a broad discretion in financial provision. In Scotland, however, with the greater respect which the Scottish courts give to ante-nuptial marriage contracts, it may be thought that a mahr, especially if expressed in a written marriage contract, may be enforced by the court unless it falls foul of s 16 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985.

Some more radical Islamic thinkers would prefer to see the UK courts treating the mahr as an essential part of any Islamic marriage, and accordingly treated as an implied contract even where it is not reduced to writing. This is surely a step too far for the Scottish courts.

Financial support

Under Islamic law the payment of any financial provision is from the husband to the wife, irrespective of their relative wealth. Claims are for income – the only capital claim the wife can make is for payment of her mahr, which may have to be interpreted according to s 16 of the 1985 Act. Income claims are payable only for the period of iddat, or to the end of the time when any child of the marriage is still being suckled.

Assets in the name of either party acquired before or during the marriage remain in the name of that party. Joint assets are to be divided in an equitable manner, failing which the Qadi will decide the matter. In respect of children the father has a continuing duty to maintain the children throughout their childhood at a level which is reasonable in the circumstances.

Questions of recognition

The Scots courts will be concerned with Sharia divorce chiefly in the context of the recognition of foreign decrees – see Family Law Act 1986, s 54 and Chaudhary v Chaudhary [1984] 3 All ER 1017; El Fadr v El Fadr [2001] 1 FLR 175; Ahmed v Ahmed 2004 Fam LB 68-7. Various Sharia councils have been set up in England to resolve civil disputes in Muslim communities. They have no recognised judicial role, of course, but their decisions are regarded as binding by those communities in which they are set up. They can only ever be courts of voluntary jurisdiction, but they are rather more deeply rooted than ordinary arbitration because of the divine nature of the law in the eyes of those who use this jurisdiction.

There is a large Muslim population in the United Kingdom, and a growing population in Scotland. There has not been the degree of general integration which most commentators anticipated a couple of generations ago. Communities practise their religion with great seriousness, though unfortunately the media tend to view that with ever lessening objectivity and sympathy. Nevertheless, although one Muslim regarding the Sharia as his personal law may not be very important to public policy, thousands of Muslims regarding the Sharia law in the same way cannot be ignored.

If law is an art it is a practical art, and if law is a science it is an applied science. If members of these large Muslim communities actually seek the jurisdiction of the Sharia councils and are willing to accept their judgments, it is at least arguable that what the councils dispense is properly described as law, even if they have none of the enforcement powers of the ordinary civil courts.

The debate about recognition of the importance of the Sharia law is overdue. We should not allow that debate to be derailed by those who confuse it with the shrill demands of some extremists who seek effectively an independent Muslim state within the UK or even within Scotland.

One can at least recommend a greater understanding amongst Scots family lawyers of what the Sharia says – the better informed a debate is, the more likely it is to produce a useful answer.

Talaq rules: first seek reconciliation

"If you fear a break between the two, appoint two arbiters, one from his family and one other from hers; if they wish for peace, Allah will cause them reconciliation: for Allah has full knowledge and is acquainted with all things": Qur'an (Koran), chapter 4:35

Valuing the mahr

The Qur'an does not give any precise formula for the amount of mahr, so early commentators had to decide on at least a minimum sum. In Medina, for example, the mahr was fixed at a minimum value of the goods in respect of which a thief had to be convicted before he was subject to the penalty of amputation.

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way