Feeling the draft?

Drafting documents is, of course, a key skill that lawyers use every day in every area of legal practice. It is no surprise therefore that claims against solicitors arising from drafting errors, omissions and ambiguities feature in the current Master Policy claims experience in every area of client work.

Failure to implement instructions

However, in many cases where it is alleged that there has been an error or omission in a document, it transpires on analysis that the underlying cause is not poor draftsmanship at all but a failure to implement the client’s instructions. Consider this case study:

A firm had acted for the seller of a small country estate. One of the partners had taken instructions from the client, who had clearly specified that he wished to retain a two acre paddock for future development. The partner passed the file to an assistant who dealt with the missives and conveyancing. The assistant omitted to provide in the missives that ownership of the paddock would be retained by the client. The client subsequently made a claim against the firm.

In this case, the underlying cause of the claim was not that there was an error or omission in the drafting of the missives or that the assistant had simply forgotten the client’s instructions: it was a failure to give effect to the client’s express instructions. Somehow the partner had failed to pass on those instructions to the assistant. There are practical risk controls that can prevent communication failures of this kind. A detailed note for the file by the partner recording the client’s instructions, and/or a detailed handover note to the assistant or, wherever possible, arranging that the colleague who will be carrying out the work attends the meeting with the client, will minimise the risk of any aspect of the client’s instructions being overlooked.

Claims have also arisen where the responsible fee earner is fully aware of the client’s instructions but nonetheless the document drafted by the fee earner does not reflect those instructions.

A client instructed his solicitors to draft a will leaving a liferent in his house to his disabled son and the residue of his estate to his daughters. Owing to an error in the will drafted by the solicitors, the son received a quarter of the residue on the client’s death.

A clearly enumerated note of the points to be included in the draft will and a comparison of the draft against that note, or the written record of the client’s instructions, would have helped prevent the error in the will.

There are instances of claims arising out of conveyancing transactions, where the missives correctly reflected the client’s instructions but the instructions were not carried through to the subsequent conveyance.

In terms of the missives the seller of property retained a right of access to his adjoining land, but this right was omitted from the disposition. The problem only emerged after the missives had expired. The seller intimated a claim against his solicitors for the reduction in value of his property, the right of access having been lost.

A methodical approach of highlighting provisions in the missives to be incorporated into the conveyance and then checking those provisions off systematically would minimise the risk of omissions.

Failure to appreciate a risk

Another type of claim, often ascribed to defective drafting (but where the true underlying cause is not a defective drafting issue at all), is illustrated by the following scenario:

It was provided in a separation agreement that an insurance policy was to be transferred to Mrs D. The policy could not be transferred because it had lapsed when Mr D ceased payment of the premium. Mrs D intimated a claim against her solicitors alleging defective drafting of the agreement in respect that it omitted to bind Mr D to continue paying the premium.

In this particular case the problem was not so much a drafting omission, but rather a failure by the solicitors to appreciate a risk (that the ex-spouse would stop paying the premiums) and then provide the appropriate contractual protection for the client.

A useful risk management control to address this is a checklist of issues for each of typical transactions or cases handled by the firm, amended, as appropriate, for the particular transaction or case, including a risk assessment focusing on potential risks and worst case scenarios.

Complexity

Missives for the purchase of a housing development were subject to a suspensive condition relating to planning. In order to keep the missives alive, the developers instructed their solicitors to waive the condition. The responsible partner had been about to depart for a fortnight’s holiday at the point when the developers were making up their minds about the planning condition and the file was left with an assistant who had recently joined the firm. The missives were extremely complex, running to six or seven formal letters and the complex price-setting arrangements were dealt with in the same set of provisions as the planning condition. Waiving the planning condition had the unintended effect of crystallising the price payable by the developers at the fixed price specified as the default position in the missives. The developers made a claim for the difference between the fixed price they ended up being committed to and the lower price they would have been bound to pay in accordance with the price-setting formula.

While issues such as lack of supervision of a junior solicitor may have been a contributing factor, there can be little doubt that the complexity of the missives, leading to a failure to appreciate the consequences of the waiver, was the main underlying cause of this claim. Consider, where possible, structuring missives in a way that keeps issues distinct. Many firms adopt the approach of adjusting a draft offer so that there is a single contract document. Having a colleague test the effect of the proposed waiver before it was sent to the seller’s solicitors might have brought the unintended consequence to light.

Typographical/word processing errors

It may be thought that, with the almost universal use of word processing software, comparison of documents is a thing of the past. Not so – as the following recent examples from the claims experience illustrate:

- In a separation agreement the number of a life policy to be assigned was mistyped.

- A typing error in a will caused part of an estate to fall into intestacy.

- A clause specifying the length of a consultancy agreement was accidentally deleted from the final draft.

- Owing to a typing error, missives were concluded for a price that was £500,000 less than the intended price.

Enough said!

Ambiguity

Typographical/word processing errors aside, perhaps the main type of claim which truly results from poor drafting is ambiguity in the document. Sometimes claims arising from drafting ambiguities can arise because words or phrases are used in the document are not defined in the document itself and have no standard, well understood meaning.

A firm acted for tenants in taking a lease over commercial premises. The rent review clause provided that the rent would be reviewed (upwards only) every five years with the rent being reviewed by the greater of 2.5% or the “average prime office rental in the centre of Glendale”. Five years later the landlords sought a 50% increase in rent. They argued that the “prime office rental” in question should be determined by the three plush government quango offices recently erected as a result of devolution from Edinburgh. The landlords argued that all other office space (at much cheaper rentals) was no longer in the category of “prime” and should be disregarded. The dispute was referred to arbitration under the lease and the arbiter awarded a 45% increase in the rent. The tenants sued the firm, alleging that they were unaware that such a large increase could have been awarded and that they would not have agreed to the terms of the lease if this had been explained to them.

In this case, the phrase “prime office rental” was not defined in the lease itself, and that often sows the seeds of a later dispute. Clarifying both the client’s understanding of the landlords’ intentions and his instructions with input from a surveyor might have made it possible to use more precise language. A full written record of the advice given and the risk being assumed by the client would have provided the firm with a defence to the allegation that the terms of the lease had not been explained to them.

In a recent communication, Master Policy lead insurers stated: “Master Policy Insurers have seen a number of cases where rent review clauses are variously void for uncertainty, ambiguous, or clearly very much in favour of landlord or tenant, and the client (whether landlord or tenant) later complains they did not understand this. The claims can be expensive and time-consuming for all parties.”

It is not only unusual clauses that can cause problems of interpretation.

A firm acted for the sellers in the sale of their shares in A Ltd. Much of the value of A Ltd comprised debts owed to it by customers. In the share sale agreement, the sellers gave the purchasers a warranty that the book debts “either have been realised in full or will be realised in full in the normal course of collection not later than 120 days from Completion”. The sellers brought a claim against the firm when the purchasers retained the second instalment of the price on the basis of a claim for breach of the warranty, arguing that the words “in the normal course of collection” did not require them to take court action against customers for recovery of unpaid debts.

Consider avoiding the use of words such as “normal” which, as in the case study, can lead to arguments about what is “normal” in any given situation. More precise wording outlining what actions required to be taken, or not taken, could have minimised the risk of a claim, particularly since the recoverability and value of the book debts was a critical feature of the transaction.

Russell Lang is a former solicitor in private practice who works in the FinPro (Financial and Professional Risks) National Practice at Marsh, the world’s leading risk and insurance services firm. To contact Russell, email: russell.x.lang@marsh.com .

The information contained in this article provides only a general overview of subjects covered, is not intended to be taken as advice regarding any individual situation and should not be relied upon as such. Insureds should consult their insurance and legal advisers regarding specific coverage issues.

Marsh Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Services Authority.

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

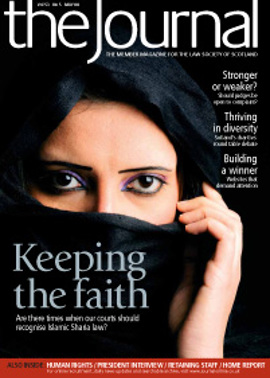

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way