Sheriffs behaving badly

Sheriffs are just like everybody else. We all make mistakes; we all have bad days. This article is about what happens when the mistakes are repeated, or the bad days become weeks, months or years. And what we should be doing about it.

We all make mistakes…

Several years ago, for reasons I can’t remember, I wrote to the Scottish Office (as it then was) asking if anybody there kept statistics on judicial performance. I was particularly interested to see whether they kept tabs on sheriffs’ appeal records. I was pretty surprised when they replied that they didn’t keep any such statistics at all. It seemed to me that there was at that time no monitoring of sheriffs’ performance on the bench. A case could therefore be made that in no other area of public service are so many people with so much power exposed to so little effective public scrutiny.

While researching this topic, I came across a reference to concerns expressed in the House of Commons by an English MP, following newspaper reports claiming that there were certain English judges who were four or five times as likely to be appealed as their colleagues and who were frequently criticised by the Court of Appeal. From the answers given on behalf of the Department for Constitutional Affairs, it would appear that no statistics were kept in England either, as it was thought that to do so might be perceived to amount to political interference.

Anyway, even if appeal statistics were kept, where would that take us? If, for example, we knew that Sheriff X’s charges to the jury kept resulting in convictions being overturned, or if we knew that Sheriff Y was repeatedly criticised for the ineptness of her civil judgments, what exactly would be the consequences for those sheriffs? Should it not be possible for sheriffs to be ordered to undergo, for example, retraining? What level of judicial error should we be prepared to tolerate? Who else in public life would get away with such a lack of consequences?

Now, I have no idea whether any sheriff actually fits the above bill(s). I think I’m correct that, in the relatively recent past, only one sheriff has been compulsorily removed from office. In that case, however, I remember hearing about his antics long before his removal. The stories were the stuff of common room gossip.

I realise that removing a sheriff is an extremely serious business, but space doesn’t allow me to get into just how cumbersome are the relevant procedures. My point, in any event, is this. Yes, the sheriff was ultimately removed, but it took an awfully long time.

It’s also rather odd that when I read appeal judgments, the sheriffs against whose decisions appeals have been taken are almost never named by the appeal judges, whether in the Inner House or the criminal appeal court. Why is that? Counsel and agents are often named and shamed – why not sheriffs? This seems to be a matter of our national judicial culture. While I was writing this article, my attention was drawn to some examples of misbehaviour by judges in England. In one case, the appeal judges did not shy away from severely criticising the judge below, but also repeatedly referred to him by name.

We all have bad days…

In any event, and while the appeals process acts at least as a corrective to bad decisions, what about what happens on the way to the decision being made? What about plain old bad behaviour? I remember for instance being appointed curator ad litem in a children’s hearing case to a child with emotional problems. When in court, he remained mute and refused to answer any of the sheriff’s questions. The sheriff then proceeded to yell at him and tell him he was just being rude. It seemed to me he’d clearly not read the papers. If I’m wrong about that, then he’d even less excuse for such poor behaviour. Both I and the children’s reporter in the case were quite appalled. I’m sure we could all add other examples.

Anyway, my point is this: ought there not to be some way of addressing behaviour that most observers would regard as unacceptable? Yes, you can appeal, but very often it’s not the outcome of the case that’s the problem – it’s the process. I’d argue the current situation is clearly unsatisfactory in any sense. For example, assuming you want to make a complaint about a particular sheriff, how do you go about it? To whom do you complain? Most solicitors I’ve spoken to don’t even seem to know. Scottish Courts? The sheriff principal? What will they do? Will you even find out if anything is done to address your complaint? I know one or two solicitors who asked to speak to sheriffs privately to express unhappiness at how they felt they’d been spoken to. Frankly, though, most wouldn’t even think about complaining.

It therefore seems to me not just that judicial appraisal is necessary and desirable in a modern democracy – the surprise is that we’re only talking about it now, and talking about it openly. Isn’t judicial appraisal just quality control? And, in turn, isn’t quality control at least partly about transparency? How can the public have confidence in its judges without it?

… but we don’t bother to check

It’s instructive to look at how all of this is done elsewhere.

Even a casual trawl of the internet brings up numerous examples of how other countries manage things differently. For example, some American states publish in detail judicial performance on websites, although it has to be acknowledged that this probably arises from the fact that judges are elected officials there. Other states have independent judicial review boards. For example, Colorado in 1988 set up a commission on judicial performance for the purpose of providing voters with responsible and constructive evaluations of judges and justices seeking retention. Judges are also expected to self assess.

The ideal of self appraisal seems to have been taken up in England, as I understand it, in the case of part time judges. I am not aware of any plans to do the same thing here for part time sheriffs, although I accept that applicants for shrieval positions have to engage in self assessment. Why, however, should the process of self assessment stop on appointment? Why in fact should the process of assessment tout court stop on appointment?

Anyone applying to the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland has to demonstrate that they meet a number of criteria: for example, that they are courteous, possess integrity and sound temperament, can deal with complex issues, and so on. Now, we can all say, of course we have those qualities; and of course references are required when applying. Where exactly is the check, however, that the successful applicants are in fact meeting those criteria on the bench, where it really matters?

I appreciate that part time sheriffs are subject to review every five years, but that’s to do a disservice to the word “review”. I’ve no idea, for example, how their performance is actually reviewed. I do know, though, that the JABS does not carry out the kind of poll of court users referred to earlier. I have no idea what criteria it even applies in deciding whether or not an applicant’s appointment should be renewed. I’ll make a suggestion of my own, though – how about the JABS publishing the names of appointees seeking retention, and inviting informed comment?

A minority? So what?

Yes, it would be easy to say that the vast majority of sheriffs probably do their jobs perfectly well, and treat the public, agents and other court users with respect. That’s probably even true. It wouldn’t be the point, however. Going to court is stressful enough for most people, and a bad sheriff can make it so much worse. (Conversely, good sheriffs can really create a feeling that justice has been done, even if the outcome is adverse.) Why should even a minority get away with bad behaviour? It’s precisely the minority that have the potential to undermine public confidence.

I also appreciate that there’ll be entirely legitimate concerns about opening the floodgates to frivolous complaints against our judges, about ending up with a judiciary that feels itself beleaguered and undermined. I don’t want to see sheriffs having to defend themselves in the press either. Nevertheless, it must be possible to strike a balance between the need for scrutiny of the judiciary and the need for judicial independence. We surely can’t say that such a balance can’t be found, and in any event, we’ve hardly even made a start.

It’s therefore very much to be welcomed that the Scottish Government is finally addressing these issues. It’s just a pity we’ve had to wait so long. It’s also a great pity that the momentum here didn’t come from the profession.

Postscript: Just so everything’s open and above board, yes I am one of the many unsuccessful applicants for a part time sheriff’s position. But I have no criticism of the interview process, and thought it entirely fair and reasonable. And no, I’m not saying that because I might want to apply again!

(A number of people helped me with this piece, some of whom asked for their contributions to be anonymous. I’d like, though, to thank Sheriff Andrew Cubie in particular for his valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.)

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

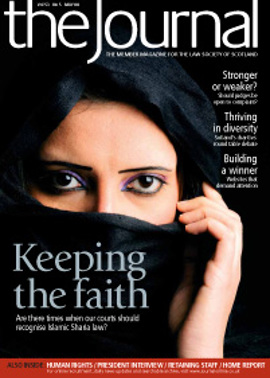

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way