Summary trials: deciding the facts

If witnesses were not questioned and simply volunteered information in the witness box, nothing would come between them and the bench. But in our courts, lawyers, acting as advocates, intervene in this relationship. They select the witnesses and control and edit their testimony.

As partisans in a situation of conflict, the advocates’ presentations of this evidence are guided by persuasive tactics. Undoubtedly all this must influence a court’s decisions about facts in some way. Any study of the decision-making process must take the role of advocacy into account. But this is a large and complex subject. The present discussion only focuses briefly on how several salient features of advocacy play a part in determining the facts.

Examination in chief

In examination in chief, advocates lay the foundations of their cases. Their selections of witnesses completely determine the sources of testimony which a court can hear. Additionally, the advocates largely control the flow of information from these sources. Further, with significant skill, they present this evidence in ways which they expect will persuade the court to convict or acquit the accused.

Selection of witnesses

Prosecutors call at least as many witnesses as they need for corroborative evidence which may lead to convictions. Ethical questions may arise about when they should include witnesses who might support the defence. The defence need not call any witnesses, but usually does. Courts sometimes draw incriminating inferences if the accused does not testify. In deciding the number of witnesses each party may balance the possible gain from increasing the volume of testimony against the added risk of harmful inconsistencies.

Selection of evidence

So far as possible, advocates control what their witnesses say, usually on the basis of their precognitions. Advocates avoid questions to which they cannot foresee the answers. To a great extent, evidence in chief tends to be predetermined and inflexible.

But a wise rule prevents advocates from putting words into their witnesses’ mouths by leading questions, except on undisputed matters.

Yet advocates cannot control evidence in chief completely. Witnesses may unexpectedly forget or remember something, develop doubts, change their minds or express something in an unwanted way.

Despite these occasional deviations from an advocate’s control, however, on the whole evidence in chief is usually what parties want and expect – not a spontaneous report, even if it is truthful.

Tactical presentation of testimony

A whole book would be required for a detailed description of the presentational skills of advocacy and their influence on factual judgments. Undeniably, advocacy is not a neutral component of criminal trials. Whatever the standard of skill may be, advocacy can be expected to make a difference to some extent. But it would be unacceptable if advocacy alone determined the outcomes. Fortunately for the administration of justice, that is certainly not the case.

Re-examination

Re-examination is an opportunity to repair damage caused to testimony by cross examination, or to clarify something or fill a gap, but not to examine the witness in detail again. Re-examination is optional and is often omitted. It is generally the least persuasive stage of questioning witnesses. Its significance for the court depends on the circumstances.

Cross examination

In cross examination, parties,in effect, confront one another and two contradictory versions of the facts become explicit. Cross examination may be of three types:-

New facts or perspectives

All witnesses are bound by law to testify truthfully and accurately, irrespective of the party who called them and the outcome their evidence may support. So cross examination of opponents’ witnesses is often aimed at eliciting new facts, or modified ways of looking at facts about which the witness has already spoken. This may be effective and helpful to the court with truthful witnesses. Such additional evidence could be very persuasive. It is difficult for advocates who called witnesses to support their cases to challenge their further evidence when re-examining them.

Mistaken testimony

Cross examiners routinely try to undermine adverse evidence by contending that it is mistaken, uncertain or incomplete. Grounds for this approach were discussed in the second article.

Simply suggesting such defects without probing how they arose will just invite denials. Sound cross examination aimed at exposing mistakes, doubts or gaps in evidence can be of real help in the court’s assessment of testimony.

Lying testimony

It is common for cross examiners to allege that witnesses are lying. This criticism may seem to be unfounded unless it is shown that they have some significant motive for doing so. Lying in court for trivial reasons or for no reason at all would be odd.

The credibility of evidence may be challenged effectively on the grounds discussed in the first article. But unsupported suggestions that witnesses are lying may have little or no effect.

Good cross examination which challenges testimony effectively may have a substantial impact on factual judgments by highlighting and exposing a lack of credibility or reliability. But even if strong cross examination fails in its aims, it may still serve a useful purpose for the court by testing and reinforcing adverse evidence – although the cross examiner did not intend this.

Sometimes a cross examiner must challenge the adverse evidence of witnesses who know the facts, by putting his/her own case to them for comment in order to avoid the risk of the court’s inference that the cross examiner has accepted the adverse evidence.

Even attacks on credibility or reliability without demonstrable grounds may occasionally have a suggestive effect per se, namely, as discussed in the second article, the acceptance of an idea simply because it is presented. But it is to be hoped that courts would resist such influences.

Final speeches

Final speeches summarise the evidence and present arguments for conviction or acquittal. Whether or not speeches add greatly to the effect of the evidence varies according to the situations and advocates’ abilities.

Judgment on the facts

A court’s decision about the facts in a trial has several aspects.

Time for decision

The bench should decide the facts when it is considering the verdict. All the evidence and speeches can then be compared and weighed. Earlier decisions would be based on incomplete information and disregard of much of the trial process, including advocacy. Early views should only be provisional, not final. An open mind throughout the whole of a trial is proper judicial practice.

Basing decisions on all the evidence

The great virtue of a criminal trial is that it can ascertain the truth by comparing interlocking or conflicting information from multiple sources after it has been thoroughly tested.

The material considered by the bench includes the witnesses’ personal qualities, particularly their motives. The credibility and reliability of the information which they provide is scrutinised carefully after the advocates have striven to expose internal inconsistencies and improbabilities in their opponent’s testimony.

The key to reaching correct decisions about the facts in a trial is this total approach rather than any single factor in the evidence.

Weight of the evidence

The weight of evidence is its cumulative persuasive effect and is a matter of personal judgment. This is a different concept from the legal sufficiency of evidence, which refers to corroborative proof of guilt. The weight of evidence also differs from the volume of evidence, which refers mainly to the number of witnesses who support a particular version of the facts. The volume of evidence, like the agreement of a number of witnesses about certain facts, sometimes adds to its weight. But a large number of witnesses could all be lying or mistaken, whereas a solitary dissenter could be truthful and accurate.

The weight of the evidence about both the commission of the crime and the accused’s responsibility for it, must attain the standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt for conviction. For an acquittal, the weight of the evidence need only fail to reach that standard on either of these two main issues.

The nature of judgment

This final discussion of judgment has so far focused on its objective and practical aspects. However further exploration of the process of judgment itself is best left to cognitive psychologists and logicians. It is questionable whether anything of practical value for lawyers would be contributed by these sources.

No tribunal of fact is infallible. But given the necessity of the rule of law, and despite human limitations, no better way than a fair criminal trial for ascertaining the truth about unacceptable conduct seems to exist anywhere in the world.

How advocacy influences decisions about facts

If advocacy had no effect on a court’s decisions it would be pointless. But it is impossible to state any general conclusion about whether advocacy helps or obstructs the accuracy of assessment of evidence. It may do one or the other in different trials and different circumstances. Also there are too many variables for any such opinions. Two unacceptable generalisations are: “Good advocates always win their cases”, and “It’s the evidence that counts, not the advocacy”.

The risk that advocacy may unintentionally mislead courts so that they decide facts wrongly is always reduced, and often eliminated, by three important factors which are present in every criminal trial.

The real facts

What actually happened is one, although it may not be the only, determinant of evidence. The truth is often robust. A victim’s injuries or the vandalisation of a car are hard to deny. Theft of household contents cannot be easily misconstrued as a charitable donation. A street riot can scarcely be presented as a happy carnival. Evidence of intangible facts, and visual identification, are more vulnerable to misjudgment. But in a vast number of situations the true facts tend to resist misrepresentation.

Professional ethics

Knowingly misleading the court would be a serious breach of a lawyer’s professional ethics and legal duty.

Judgment

Ultimately, good judgment is the guard at the gate. It is to be expected that members of the bench are experienced in separating the probative value of testimony from the way in which it is presented – especially if they have, themselves, practised as advocates.

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

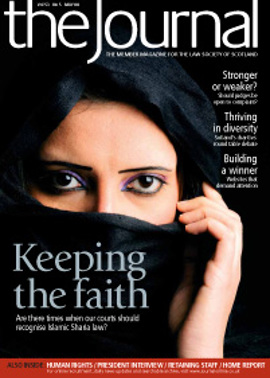

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way