The benefit burden

Child benefit. Child tax credit. Working tax credit. The current UK benefit system presents a complex array of options providing varying degrees of support for families. But what constitutes a “family” for the purpose of these benefits, and what implications does that have for those in most need of support?

There are now a variety of different domestic arrangements which involve caring for a child. A child may live with both parents, or only one. In particular, a child whose parents are separated may divide his or her time between two households over the course of a week.

This last arrangement can cause often unforeseen issues when it comes to receipt of benefits. Ultimately, “shared care” does not translate into shared benefits. Some benefits, child benefit in particular, can only be paid to one individual for one child. Where there are two children, parents can elect that each receives the benefit for one child. However, the benefit for one child cannot be divided between two parents, and must be paid to the parent with “main responsibility” for the child. This can cause real difficulties, particularly where one or both rely on benefits as a principal source of financial support.

Revenue policy; CSA rules

The relevant legislation (the Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992) fails to provide specific guidance as to how child benefit should be dealt with in situations of shared care, stating merely that where parents do not elect who is to receive child benefit in such a situation, the Secretary of State will use his discretion to make a determination. In reality this power is delegated to HM Revenue & Customs.

The policy not to divide payment of child benefit between two individuals was unsuccessfully challenged in R (Barber) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2002] 2 FLR 1181, where the court ruled that the Secretary of State’s refusal to split child benefit payments did not amount to discrimination.

This issue is one of which the prudent family law practitioner must be aware in order to ensure a client enters into a shared care arrangement in full knowledge of all potential consequences.

The issue becomes more complex due to the direct correlation between receipt of child benefit and assessments by the Child Support Agency. In short, if the CSA cannot decipher who is the parent with care and who is the non-resident parent, it will look to who receives the child benefit, and that party will become the only “parent with care” for assessment purposes. This provision can be found in the Child Support (Maintenance Calculations and Special Cases) Regulations 2000, reg 8(2)(b).

A cautionary tale

In extreme cases this can produce alarming and inequitable results. This was the position in which a recent client found herself. She had separated from her husband, with whom she had one child. On separation they agreed to share care equally between them. They entered into an agreement whereby the client assigned the child benefit to the father in recognition that he was paying specific childcare costs. The father earned considerably more, and the client eventually submitted an application to the CSA. This was refused because without the child benefit she was the “non-resident parent”. The father then retaliated with his own CSA application and was successful. The client, with an equal share of care and a significantly lower income, had no choice but to make maintenance payments to the father. She had sought advice from another firm at the point of entering into the original agreement, but had not, evidently, been advised of all the potential pitfalls of relinquishing child benefit.

While this example is perhaps an indication of one of the most serious consequences of the prohibition against sharing benefits, other effects are worthy of note. For example, receipt of child benefit brings with it another less known advantage, in the form of the Home Responsibilities Protection Scheme. This applies to individuals who care for a child under 16 and bolsters that person’s entitlement to a state pension where they may otherwise have had insufficient national insurance contributions.

Further, child benefit is not the only benefit which must only go to one person in respect of one child. Child tax credit and the childcare element of working tax credit are subject to the same restriction.

In short, a client entering into a shared care arrangement needs to be aware of the potential impact on receipt of benefits. Although it may be impossible to provide total security for clients who find themselves in this situation, a carefully worded agreement can seek to remedy any inequities privately between parties, provided they are anticipated and dealt with accordingly.

- One Parent Families Scotland provides helpful information on the benefits system which may be of use to both practitioners and clients.

In this issue

- Up for the challenge

- Paralegal regulation - why?

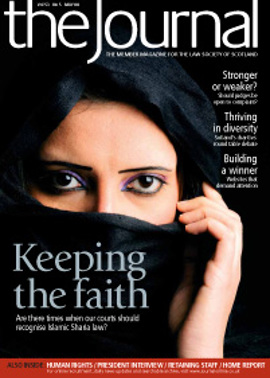

- Faith in the law

- ARTL: The Full Monty

- Giving their all

- Full of the joys of spring?

- A backward advance

- Sheriffs behaving badly

- Summary trials: deciding the facts

- Soft law, hard edge?

- Hands-on chief

- A new framework for Europe

- The ABCs of SEO

- Creating an award winning legal website

- This means war

- Feeling the draft?

- Audience on your side

- The reason of age?

- The benefit burden

- Signing away family rights

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website reviews

- Book reviews

- A better buy

- Tenders: a better way