Book reviews

This book aims to provide a clear, succinct and useful guide to mediating in Scotland. It is aimed not just at mediators but at those referring clients to mediation, advising and supporting them through the mediation process and implementing the outcomes achieved.

Its strength lies in the short and focused chapters, each of which deals with a particular type of mediation, written by an experienced practitioner in the area concerned. It is a key resource for guiding practitioners as to whether a particular dispute is suitable for mediation, and if so, how to identify an appropriate mediator and guide a client through the process.

The development of mediation in Scotland over the last 30 years has been phenomenal. As a jurisdiction we are at the forefront of innovation in this area of dispute resolution. Mediation has a success rate of over 80% in some sectors. The key criteria to success are the appropriateness of the referral, the parties’ expectations of the process and the preparatory work undertaken for the first session.

Information is also provided regarding the valuable work done by the Scottish Mediation Network, which maintains the Scottish Mediation Register, an online resource listing all individual mediators and services in Scotland. Mediators on the register practise within a code of practice, meet training requirements, and have appropriate insurance cover together with a complaints procedure.

I particularly commend to practitioners David Semple’s chapter on commercial mediation. Commercial mediation commonly involves two mediators, one of whom has experience in the relevant field. The parties are usually accompanied by their advisers, who can assist the mediators by focusing the issues, providing a factual summary of the case, an outline of the legal issues, and a note of the areas of common ground, the points in dispute and the history of negotiations prior to mediation. Copies of key documents and background information require to be collated, and it is helpful for the parties to have an estimate of the likely time frame and cost of litigation.

The term “commercial mediation” covers a wide umbrella of family business disputes, partnership dissolutions, corporate issues, construction disputes, professional negligence claims etc. The process allows for flexible, creative and sophisticated arrangements which are future-focused and allow the option of preserving professional relationships rarely open to those involved in litigation, while also saving significant time and cost. The confidential nature of mediation is also often of value to clients.

The timing of a referral to mediation can be critical. John Moffat’s chapter on employee/workplace mediation will be of interest to many engaged in advising employers on the prospect of early intervention as an option to avoid employment tribunals and claims which can have a huge impact on their clients’ business in terms of time, resources, morale, performance levels and damage to reputation.

Marjorie Mantle’s chapter provides a pragmatic guide for those advising clients in disputes with a value of under £3,000 on the option of in-court mediation, as an alternative to instructing advisers, where the fee is likely to be disproportionate to the value of the claim, or attempting to present a small claim proof as a party litigant, neither of which will provide an appealing option to a client who may well provide other valuable sources of business to your firm. The flow charts and case studies in this chapter are particularly helpful for setting out the options and procedure to clients.

The chapters on family mediation, additional support needs mediation, and peer mediation in schools will be of interest to family lawyers who may have focused to a greater degree on collaborative law as an alternative to mediation in family law disputes. While collaborative law is a good option in many cases, it should not be forgotten that mediation is the only option which focuses on allowing the parties to take responsibility for their own solutions and emphasises the value of improving communication between the parties as a basis for avoiding future disputes.

This book provides a valuable service by informing practitioners of the mediation resources available in a broad range of contexts. Its pragmatic focus allows solicitors to identify whether a particular dispute is suitable for mediation and, if so, how to make a referral to an appropriate mediator and how to better understand their role in supporting and advising clients throughout the mediation process and achieving the best possible outcome.

Wendy Sheehan, Sheehan Kelsey Oswald, Edinburghg

Conflicts of Interest Third edition

Every book has its individual strengths and weaknesses. When a title reaches its third edition, it is an indication that, for a significant proportion of readers, it is the strengths which predominate. It is easy to see why that should be in the case of the new edition of Conflicts of Interest.

The book’s area of strength is conflicts of interest as they affect lawyers and accountants in commercial practice, especially mergers and acquisitions. In that area, the work is highly impressive, as one might expect from a silk at the English commercial bar and a former accountant turned barrister.

The significance of the House of Lords decision in Prince Jefri Bolkiah v KPMG [1999] 2 AC 222 is something of a theme running through the book, and other important cases are also dealt with in detail.

Particular notice is taken of the more recent House of Lords authority, Hilton v Barker, Booth and Eastwood [2005] 1 WLR 567. The defendant solicitors had acted for one Bromage in connection with company management offences and his associated bankruptcy. On his release from prison, Bromage sought to acquire land for development of flats with the plaintiff, Hilton. The defendants were instructed in three transactions: the purchase of the land by Hilton; the purchase of the flats by Bromage once they were built; and a contract whereby Bromage sold on the flats to a third party without Hilton’s knowledge. The solicitors did not tell Hilton about Bromage’s conviction or bankruptcy because they considered they owed a duty of confidentiality to Bromage. They arranged for Hilton to be advised and represented by one of their junior employees. The third party disappeared without completing the purchase and Hilton ended up sustaining a massive loss.

The Lords were scathing about the solicitors’ conduct, emphasising the principle in Moody v Cox [1917] 2 Ch 71: “if a solicitor is unwise enough to undertake irreconcilable duties it is his own fault, and he cannot use his discomfiture as a reason why his duty to either client should be taken to have been modified”.

Bolkiah, Hilton and other cases such as Marks and Spencer plc v Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer provide the context in which Hollander and Salzedo provide detailed and impressive analysis of the conflicts which can arise in the commercial world. For those whose interests lie in that world, the book is an obvious purchase.

There are, however, relative weaknesses. One is the treatment of Scots cases. Of course, it would be unreasonable to expect a book about English law to offer comprehensive analysis of the position in Scotland. Perhaps, though, it is not too much to ask that English authors should get the basics right when they refer to Scots authorities. The treatment of Starrs v Ruxton 2000 JC 208 is disturbing. The case is described as unreported, when it is reported in three Scots series and in two series of human rights reports with UK wide coverage (a similar mistake is made with Kearney v HM Advocate 2006 SC (PC) 1). The authors assert incorrectly that the case was before the Court of Session (and initially refer to a “Deputy Sheriff”). They also report the argument as though it was the ground of decision and, as a result, overemphasise (by comparison with what was decided) the Lord Advocate’s role in the appointments and renewal process.

The significance of this is not that it irritates Scottish reviewers but that it calls into question the reliability of the treatment of cases from other jurisdictions outside England & Wales. These are of some importance in the analysis. Beyond that, it is also part of a general relative weakness in the treatment of the human rights aspect of the subject. The book is generally characterised by detailed and incisive analysis but, by comparison, the treatment of the Strasbourg jurisprudence on judicial independence feels rather superficial. The same is true of the rather brief coverage of the reporting obligation under s 330 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. In considering the position of solicitors, one might have expected some treatment of Ordre des barreaux francophones et germanophones v Conseil des ministres (Case C-305/05, 26 June 2007), which deals with the interaction in European law of the duty of confidentiality to the client with the requirement to report facts indicating potential money laundering.

Nor is there very much coverage of the position in criminal cases. Woodside v HM Advocate [2009] HCJAC 19, which postdates the book, exemplifies the sort of conflicts which can arise in criminal and general litigation practice. It is disappointing not to find some consideration of the English cases R v Saracoglu [2003] EWCA Crim 2244 and R v Morris [2005] EWCA Crim 1246, in both of which the defendant’s solicitor also acted for his proposed incriminee, with catastrophic results. In Saracoglu the Court of Appeal observed: “The mere fact that solicitors or counsel may have accepted instructions or continued to act in a situation where a conflict of interest exists between their client and a co-defendant represented by the same solicitor cannot in itself be regarded as a ground of appeal. The question must always be whether that fact or some step taken or omitted as a result of, or influenced by, that fact, has given rise to unfairness in the course of the trial and/or affects the safety of the conviction”; and in R v Morris the court pointed out that important material was not put to certain witnesses “because the entire defence strategy and effort was pervaded by the conflict of interest” which a solicitor had allowed to arise.

So the book has strengths and weaknesses. Its strengths are impressive and they justify the investment. For those who seek a detailed consideration of the law on conflicts of interest in commercial practice, or of the philosophical underpinnings of the law, it is outstanding. It does, however, have to be read with an awareness that (like most books) its content is influenced significantly by its perspective.

In this issue

- Solicitor advocates: the future

- For the love of it

- Not to be denied

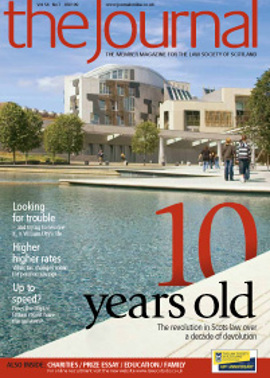

- Ten years on

- Never say never

- MD becomes new Keeper

- Whose view prevails?

- Scant relief?

- The greater good

- Twenty out of ten

- First class

- Clean break

- Ask Ash

- Not quite switched on

- Beware salary waiver tax traps

- Road to recovery?

- ASBOs: what standard?

- Scotland the unready

- The limits of listing

- Debt traps

- Tread warily

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Procurement remedies take shape

- Clauses become more standard