Not to be denied

Last year, SCCYP published “Not Seen. Not Heard. Not Guilty.” Exploring the rights and status of the children of prisoners in Scotland at all stages from arrest of the parent through to imprisonment and release, it found that, at present, decisions to imprison a parent rarely take account of the potential impact on children.

Many who read the report were shocked to learn that the estimated number of children affected by imprisonment of a parent in Scotland is similar to the number looked after by local authorities. Yet, while looked-after children are rightly the focus of much social and political concern, often the rights and needs of the children of prisoners are not only unmet, but unseen.

SCCYP believes that in this respect the current approach to the sentencing of parents is contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

Children have the same rights as adults to respect for their private and family life under article 8 of the ECHR. The imprisonment of a parent is a prima facie interference with that right, but may be justified if it is in accordance with the law, necessary in the pursuit of a legitimate aim and proportionate to the aim sought.

Applying article 8 to sentencing decisions would require courts to assess the impact of sentencing options on the rights of any children affected, to ensure that any interference with their rights is proportionate.

Children’s rights are set out in more detail in the UNCRC. Alongside the child’s right to benefit from the guidance of a parent (articles 5 and 14), to know and be cared for by parents (articles 7 and 8) and to maintain contact during separation from parents (article 9(2)), article 3(1) is perhaps most critical: “In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.”

This suggests that when courts are considering sentencing options for parents that will impact on the child, they must take into account the child’s best interests – not as the determinative factor, but the court must, at the very least, have regard to the child’s rights.

We believe that a child impact assessment should be required at the point of sentencing. This could be a separate assessment, or form an explicit part of a social enquiry report, where ordered by the court.

In his landmark judgment in the South African case S v M [2007] ZACC 18, Justice Albie Sachs dealt with these very issues, echoing many of SCCYP’s recommendations and holding that the best interests of the child should be taken into account when sentencing a primary caregiver of young children.

Speaking in Edinburgh last month, Justice Sachs outlined the change of mindset he went through in dealing with the case. Initially convinced that the case was a simple one, involving the sentencing of a repeat offender, he was minded to recommend that it should not be heard by the Constitutional Court. But a colleague pointed out that the sentencing magistrate had overlooked the rights of the three children involved, vulnerable young people with rights independent of their mother.

“I suddenly saw three wondering, precarious, conflicted young boys with a claim on our court as individuals with their own rights, not just as an extension of their mother”, Justice Sachs explained. This realisation forced him to reconsider his position and take into account the severe negative consequences on the children if their primary carer was imprisoned.

While sentencing courts cannot always protect children from these consequences, he nonetheless believes that courts can and should “pay appropriate attention to them and where imprisonment is being considered, courts must use the paramountcy principle [of the child’s best interests] to guide their decision as to which sentence to impose”.

The principle, he added, is particularly useful in borderline cases, where the offender might be suitable for a community-based alternative to imprisonment. The objective in all cases must be “to ensure that the sentencing court is in a position to balance all the varied interests involved, including those of the children”. This should become a “standard preoccupation of all sentencing courts”.

In S v M, Justice Sachs was able to draw on explicit guarantees for children’s rights in the South African Constitution, as well as international obligations under the UNCRC. Scotland may not have such constitutional provisions, but our courts should likewise have regard to the UNCRC.

By ratifying the UNCRC, the UK has, after all, committed itself to bringing its law, policy and practice into line with the Convention. There is now a strong case to be made for adjusting our criminal justice system to ensure that the rights of children are fully taken into account, and weighed in the balance, when decisions are made about the imprisonment of a primary carer.

Offenders themselves have to take responsibility for the impact of their behaviour on their children, but the state should avoid adding to it insofar as this is possible.

In this issue

- Solicitor advocates: the future

- For the love of it

- Not to be denied

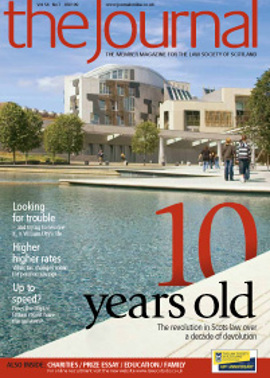

- Ten years on

- Never say never

- MD becomes new Keeper

- Whose view prevails?

- Scant relief?

- The greater good

- Twenty out of ten

- First class

- Clean break

- Ask Ash

- Not quite switched on

- Beware salary waiver tax traps

- Road to recovery?

- ASBOs: what standard?

- Scotland the unready

- The limits of listing

- Debt traps

- Tread warily

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Procurement remedies take shape

- Clauses become more standard