The limits of listing

Listing is a mechanism designed to manage and safeguard any changes made to buildings of a special architectural or historic character. If such a building appears on the statutory listing, you must obtain listed building consent from the relevant planning authority if you wish to demolish, alter or extend internally or externally a listed building in any manner that would affect its character as a listed building. It is a criminal offence to carry out such works without this consent.

The listing applies to the whole building or structure at the address named on the list, and covers both the interior and exterior of the building. However, just because a structure is not individually listed does not exclude it from also falling within a listing category. The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) (Scotland) Act 1997, s 1(4)(b) states that a listed building also includes “any object or structure within the curtilage of the building which, though not fixed to the building, forms part of the land and has done so since before 1st July 1948”.

The bounds of “curtilage”

The term “curtilage” is not defined in this, or any other, pieces of legislation – which often results in difficulties in ascertaining what exactly comprises part of a listed building, and thereafter what may require listed building consent for alterations.

Examples of ancillary structures falling within the curtilage of a listed building include farm steadings, boundary walls, gate lodges, garages and estate buildings. An examination of the listing schedule (available on Historic Scotland’s website) may be helpful but is not conclusive. Such structures are often the subject of development proposals (particularly for housing), and the utmost care should be taken to establish whether they lie within the “curtilage” of a listed building. If so, listed building consent in addition to planning permission will be required.

Four tests

Historic Scotland have set out four tests which are usually applied by the planning authority to determine if a structure falls within the curtilage of a listed building. These are as follows:

- Were the structures built before 1948?

This test follows the requirement in the legislation that for a structure to comprise part of the curtilage, it must have formed part of the land of the main listed building since 1 July 1948. Anything built on the land after this date will automatically not form part of the curtilage of the listed building.

- Were they in the same ownership as the main subject of listing at the time of listing?

One of the primary tests in assessing curtilage is the ownership of the buildings at the date of the statutory listing. This criterion is demonstrated in Watts v Secretary of State for the Environment and South Oxfordshire District Council (1991) 62 P & CR 366, which concerned a farmhouse, wall and barn. These buildings once formed part of one entity and were subsequently split by separate ownership. Judgment on the extent of the curtilage and listing of the farmhouse was made on the basis of ownership and physical occupation, and the fact that listing of the farmhouse took place after the property was divided.

- Do the structures clearly relate in terms of their original function to the main subject of the listing?

The leading case of Methuen-Campbell v Walters [1979] 1 QB 525 states at p 544 that for one piece of land to fall within the curtilage of the other, “the former must be so intimately associated with the latter as to lead to the conclusion that the former in truth forms part and parcel of the latter”. This will be determined by a combination of factors including the physical layout, purpose and current ownership of the buildings in question.

- Are the structures still related to the main subject on the ground?

This factor requires consideration of the physical layout and structure of the buildings. For example, examination of the buildings to see whether they are divided by any modern road that would redefine the relationship (e.g. the curtilage of a farmhouse may extend to the steading, although this may not be the case where the farmhouse is separated from the steading by a public road).

In the event of uncertainty, you must consult with the planning authority and/or Historic Scotland.

Further details on these criteria can be found in the Historic Scotland Memorandum of Guidance, currently being replaced by the Scottish Historic Environment Policy.

Until a further policy or legislation is drafted, for now any guidance as to whether a property will fall within the curtilage of a listed building rests on these four tests, relevant case law and a detailed examination of the site location.

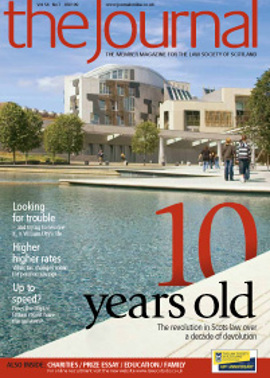

In this issue

- Solicitor advocates: the future

- For the love of it

- Not to be denied

- Ten years on

- Never say never

- MD becomes new Keeper

- Whose view prevails?

- Scant relief?

- The greater good

- Twenty out of ten

- First class

- Clean break

- Ask Ash

- Not quite switched on

- Beware salary waiver tax traps

- Road to recovery?

- ASBOs: what standard?

- Scotland the unready

- The limits of listing

- Debt traps

- Tread warily

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Procurement remedies take shape

- Clauses become more standard