A right to silence?

When Scottish Government Environment Minister Roseanna Cunningham MSP opened the International Euronoise Conference in Edinburgh on 29 October 2009, she told the 800 delegates: “The Scottish Government takes noise pollution very seriously and in recognition of our proactive stance on this problem we are proud that Scotland has been chosen to host such a prestigious event.”

Figures presented to the conference showed that Scots made 40,000 “domestic noise” complaints in 2008 — four times the annual figure prior to 2004 when new measures were introduced using the Antisocial Behaviour etc (Scotland) Act 2004.

Concurrently steps have been taken to implement European Directive 2002/49/EC on the assessment and management of “environmental noise”. The key transposition measure is the Environmental Noise (Scotland) Regulations, SSI 2006/465. Noise mapping of the Glasgow and Edinburgh agglomerations and the main road and rail links was completed in 2007 (www.scottishnoise mapping.org). Draft noise action plans for the two agglomerations, the transport links, and Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow airports – six plans in all – were prepared in 2008. Other areas have to be mapped by 2012 and action plans produced by 2013.

Right to a healthy environment

“Taking noise pollution seriously” should also mean, I suggest, being aware of the human rights dimension and acknowledging that freedom from noise can be an aspect of the individual’s right to a healthy environment.

The UN Stockholm Declaration of 1972 gave recognition to the idea that the quality of the environment was a precondition for the enjoyment of human rights. But the so-called “right” to a clean and healthy environment remains aspirational. The nearest thing to an enforceable provision in Europe – and it is still a long way off – is the diffuse article 37 of the European Union Charter of Fundamental Rights (2000):

“A high level of environmental protection and the improvement of the quality of the environment must be integrated into the policies of the Union and ensured in accordance with the principle of sustainable development.”

Nonetheless environmentalist thinking has infiltrated the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights at Strasbourg (ECtHR). In his separate opinion in the airport noise case of Hatton (2002) 34 EHRR 1 (see below), Judge da Costa actually talked about “the right to a healthy environment”.

Jean-Paul da Costa is now the President of the court.

Engaging human rights

Though there is no stand-alone right not to be exposed to too much noise as such, the right may be derived where established rights – such as freedom from torture, the right to respect for private life and home, even freedom from discrimination – are engaged by acoustic issues.

Noise as discrimination

A creative complaint outside Europe was made on behalf of the people of Okinawa to the UN Commission on Human Rights (SGC Japan 10/07/2001. E/C.12/2001/NGO/3). The claim founds on the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966), article 10, and pleads the disproportionate effect of jet aircraft noise on children and pregnant women.

In the same vein the England & Wales Children’s Commissioner has called for “mosquito” acoustic deterrent devices, audible only by young persons, to be banned under ECHR article 14 (discrimination).

Noise as torture

Billy Wilder’s classic 1961 comedy film One, Two, Three showed the East German STASI breaking a suspect with a recording of “She wore an itsy-bitsy, teenie-weenie, yellow, polka-dot bikini” (www.youtube.com/watch?v =fowuazq-140). In real life, a high-volume PSYOPS rock music attack was used by the US military in 1989 to blast General Manuel Noriega out of the Papal Nunciatura in Panama: the playlist included “The Star Spangled Banner” by Jimi Hendrix (www.youtube.com/watch?v= C2bGUeDnqPY). And “British” Guantanamo detainee Binyamin Mohamed has recently claimed that he was held in a CIA “dark site” and forced to listen to Eminem, 24/7, full volume for a month.

In Ireland v United Kingdom (1978) 2 EHRR 25 the ECtHR held that “interrogation in depth” during internment in Northern Ireland (1971-1974) amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment, but not to torture in terms of ECHR article 3. The techniques included exposure to “a continuous loud and hissing noise”. In Hatton (2003) 37 EHRR 28 the ECtHR said that the same treatment “would now most probably be considered as torture”.

Noise as pollution

The recognition that noise may be torture has made it easier to accept that acoustic events outside impacting within your home can constitute a violation of article 8 (respect for private and family life, home and correspondence). In Hatton (2002) 34 EHRR 1 there was a cri de coeur from Judge da Costa: “Anyone who has suffered for a long period from noise disturbance... is well aware that the effects of this on the nerves and on one’s physical and mental well-being are extremely unpleasant and even harmful.”

In her dissenting judgment Judge Greve noted that though the core concern of article 8 is to stop the police raiding your house without a warrant, the provision has gradually been interpreted to include environmental rights. She pointed out that environmental issues are not discrete: activities that impact on the environment may have advantages and disadvantages; and many persons may be interested, not just individuals who think they have suffered article 8 violations.

The Strasbourg jurisprudence is concerned not with the environment in general but with serious harms that intrude into the sphere of individual autonomy.

Potential liability of states

In the 1980s the European Commission on Human Rights made three admissibility decisions in article 8 cases about noise pollution. Airport noise was the issue in two of the cases (Arrondelle v United Kingdom (1980) 19 DR 186; (1982) 26 DR 5; Baggs v United Kingdom (1985) 44 DR 13; (1987) 52 DR 29). The Commission found the applications admissible and facilitated “friendly settlements”, involving the payment of compensation by the UK Government, in terms of article 28.

A key feature was that the applicants had become “locked in” to their affected homes without alternative recourse. In the later ECtHR airport cases of Powell and Hatton there was nothing to stop the applicants selling up and moving (see below).

A case found inadmissible because the noise was deemed to be not bad enough was Vearncombe v Federal Republic of Germany and United Kingdom (1989) 59 DR 194. The noise came from a military firing range in Berlin. Ironically Vearncombe applied the rule on extra-territorial effect formulated in a case involving that well-known Nazi low-flier Rudolf Hess (Ilse Hess v United Kingdom (1975) 2 DR 73).

Pollution and positive obligations

In Lopez Ostra v Spain (1994) 20 EHRR 277 the ECtHR for the first time ruled that freedom from environmental pollution was included in article 8. The complaint was about “smells, noise and polluting fumes” from a waste treatment plant built on municipal land. There were documented health effects.

Guerra v Italy (1998) 26 EHRR 357 established that states can have “positive obligations” in terms of article 8 to secure protection against non-state polluters – the polluter in that case was a private enterprise fertilizer factory. Surugiu v Romania (No 48995/99), 20 April 2004 clearly affirmed the positive obligation of states to guarantee article 8 rights against interference by private interests and individuals. The ECtHR ruled that the authorities were liable for failing to stop harassment by a neighbour who dumped cartloads of manure in front of the victim’s door and under his windows.

Noise pollution – “domestic irregularity”

Moreno Gomez v Spain (2005) 41 EHRR 40 reworked the common law concept of “a right to quiet enjoyment”: violations of the right “also include... those that are not concrete or physical, such as noise, emissions, smells or other forms of interference”.

Ms Moreno Gomez’s flat was in an “acoustically saturated zone” of Valencia. The city council had licensed 127 bars, clubs and discotheques to operate in the area. The result was serious night-time disturbance for the residents. The claim for compensation was refused by the Spanish courts on the ground that neither the cause of the victim’s alleged insomnia nor “serious and immediate damage to health” had been proved. The ECtHR was satisfied that there had been an article 8 violation on the grounds (a) that

the authorities’ own definition of “acoustic saturation” meant that residents were exposed to “high noise levels causing serious disturbance”; and (b) that the expert report by Valencia University acoustic laboratory demonstrated night-time noise levels many times in excess of those permitted by the council’s 1986 byelaw on noise and vibrations.

A common feature of Lopez Ostra, Guerra and Moreno Gomez was “domestic irregularity”: the waste treatment plant in Lopez Ostra operated without the requisite licence and was eventually closed down; in Guerra, contrary to the terms of a presidential decree, the authorities did not provide information about the risks of the fertilizer plant; and in Moreno Gomez the authorities failed to enforce the byelaw on noise.

In Borysiewicz v Poland (No 71146/01), 1 October 2008 the article 8 claim in respect of noise nuisance from a tailoring workshop next door failed because “it has not been established that the noise levels complained of... were so serious as to reach the high threshold established in cases dealing with environmental issues”. A breach of article 6 (due process) was upheld in respect of the authorities’ failure to resolve the applicant’s complaint with sufficient expedition. The delay apparently fell short of “domestic irregularity” of the Moreno Gomez kind.

Individual v the community

Article 8 is not an absolute guarantee. State interference is permitted where it is “in accordance with the law and is necessary... in the interests of national security, public safety or the economic well-being of the country, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health or morals, or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others”.

Where national laws allow public authorities to make judgments about acceptable levels of noise, the ECtHR has so far permitted a wide margin of appreciation.

In Powell and Rayner v United Kingdom (1990) 12 EHRR 355, it was conceded that the operation of a major international airport at Heathrow furthered a legitimate article 8 aim and that the negative impact on the environment could not be entirely eliminated. The court held that: “It is certainly not for the Commission or the Court to substitute for the assessment of the national authorities any other assessment of what might be the best policy in this difficult social and technical sphere.”

The Hatton decisions

In Hatton v United Kingdom (2002) 34 EHRR 1; (2003) 37 EHRR 28 the issue was whether the authorities had overstepped their margin of appreciation in introducing a more permissive regime for night flights at Heathrow. The first instance decision went in favour of the applicants. The majority enunciated a principle that “states are required to minimise, as far as possible, the interference with these [article 8] rights, by trying to find alternative solutions and by generally seeking to achieve their aims in the least onerous way as regards human rights”.

The case was referred for review to the Grand Chamber, which rejected the claim. The majority noted that “the element of domestic irregularity is wholly absent” (cf Moreno Gomez.) They also found that the state had acted within its margin of appreciation and declared: “Environmental protection should be taken into consideration by Governments in acting within their margin of appreciation... but it would not be appropriate for the Court to adopt a special approach in this respect by reference to a special status of environmental human rights.”

There was a strongly worded dissenting opinion from Judge da Costa and four others. The minority described the majority as taking “a step backwards”.

Future developments

The minority opinion in Hatton may well contain the seeds of future developments since, undeniably, environmental issues are assuming greater and greater importance.

The contrary view might be that Hatton demonstrates the limitations of a legal regime based on liberal individualism in dealing with environmental issues where judgments have to be made about the interests of the community as a whole. Indeed tackling climate change, for example, may mean curtailing traditionally-assumed individual rights and freedoms.

Freedom from noise in Scotland

It is probably a safe prediction that the opportunities in Scotland for environmental human rights challenges on the basis of “domestic irregularities” will increase. The Aarhus Convention principles about involvement in environmental planning are being received into Scots law, mediated by, for example, Directive 2003/35/EC on public participation (cf Forbes, Petitioner [2010] CSOH 01, Lady Smith, 6 January 2010).

The Environmental Assessment (Scotland) Act 2005 obliges the Scottish Government, in conformity with Directive 2001/42/EC, to consider the environmental effects of a plan, before its content is finalised. A result of that work as regards “environmental noise” is the Noise Action Plans Strategic Environmental Assessment Environmental Report (2008).

There is now an expectation, encouraged by the Government, that all “domestic noise” nuisances are amenable to control by public authorities under the Antisocial Behaviour etc (Scotland) Act 2004. And, since noise is said to be one of the commonest reasons for moving house, it must at some stage be for consideration whether the Government would be advised to make good its article 8 guarantee by amending the Housing (Scotland)

Act 2006 (Prescribed Documents) Regulations 2008 to include a specific declaration on noise in home reports.

Whatever the regulations say, it is not outwith the bounds of possibility that a court somewhere will feel bound to hold, in implementation of the article 8 guarantee, that disclosure of “material matters” required by standard form domestic conveyancing declarations extends to disputes around noise nuisances like the dreaded click-clack of stilettos on the laminate flooring upstairs.

Flora Stewart took her Master’s Degree in European Law at the College of Europe, Bruges, with a special focus on human rights. She now practises as an English-qualified solicitor in London.

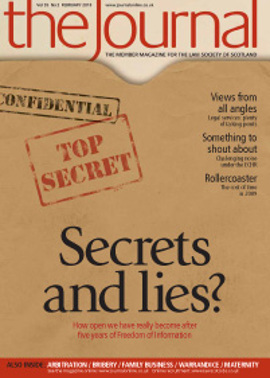

In this issue

- More prejudicial than probative?

- Another age

- Resolution is the key

- On the record

- Chequing out

- ABS workout

- Know your books

- Family business and business families

- Forum of choice?

- A right to silence?

- What does it mean to be a solicitor?

- Traineeships down over 25%

- Law reform update

- From the Brussels office

- Appreciation: Alfred Phillips

- Appreciation: John Sinclair

- Training for success

- From here... to maternity

- Ask Ash

- The move in-house - do you have what it takes?

- Big decisions

- Balancing exercise

- Belief boundaries

- Details, details, details

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Tougher regime

- No guarantees?

- Title insurance for insolvency practitioners

- PSG update