Belief boundaries

There seems to have been a spate of recent cases dealing with, first, what amounts to a religion or belief for the purposes of the Employment Equality (Religion or Belief) Regulations 2003, and then, what protection is afforded by those regulations particularly where beliefs bring a person into conflict with other protected strands, mostly notably sexual orientation.

A reminder of how widely the regulations can be interpreted was provided by Nicholson v Grainger plc (UKEAT/0219/09), in which claims of discrimination on grounds of religion or belief were brought arising from redundancy. The regulations provide protection on grounds of “religious or philosophical belief” (reg 2(1)(b)), and Mr Nicholson claimed to have a strongly held philosophical belief about manmade climate change and the need to cut carbon emissions. He contended that this was “not merely an opinion but a philosophical belief which affects how I live my life including my choice of home, how I travel, what I buy, what I eat and drink, what I do with my waste, and my hopes and fears”.

An employment tribunal held that Mr Nicholson’s beliefs did amount to a philosophical belief. They were more than mere opinion: they affected how he lived his life. Grainger’s appeal was dismissed by the EAT, who stated that a belief must be of a similar cogency or status to a religious belief to attract protection. The EAT also held that a belief must be “genuinely held”, suggesting that tribunals should not necessarily take a claimant’s professed belief at face value, but might need to allow cross examination on whether it is genuinely held. The case was remitted for a substantive hearing on whether Mr Nicholson was unlawfully discriminated against in consequence of his philosophical belief.

Direct or indirect

The expression of religious beliefs at work was considered by the EAT in Chondol v Liverpool City Council (EAT/0298/08). Mr Chondol, a social worker and committed Christian, was dismissed for giving a Bible to one service user and attempting to promote his beliefs to another. He argued this was discrimination on the grounds of his religion. However, the tribunal found that “it was not on the ground of his religion that he received this treatment, rather on the ground that he was improperly foisting it on service users”. He knew the council prohibited social workers from overtly promoting any religious beliefs in the course of their work. The EAT held the dismissal was not discriminatory, being on grounds of inappropriate proselytising rather than his religion as such.

Mr Chondol had only argued direct discrimination, and commentators queried whether an indirect discrimination claim would have succeeded: i.e. if he had been able to demonstrate that, as a member of a particular religious group with a fundamental belief in proselytising, the council’s prohibition put him (and other members) at a disadvantage, which would then have needed to be objectively justified.

This was put to the test more recently in McFarlane v Relate Avon Ltd (UKEAT/0106/09), in which the dismissal of a counsellor for refusing to work with same-sex couples formed the basis of direct and indirect claims under the regulations. The EAT held that it was not direct discrimination as he was dismissed not because of his Christian beliefs, but his refusal to abide by the employer’s equal opportunities policy. It was, however, considered to be prima facie indirect discrimination, but the employer was able to objectively justify dismissal as a proportionate means of achieving the legitimate aim of serving the community in a non-discriminatory way.

In similar vein is the Court of Appeal’s judgment in Ladele v London Borough of Islington [2009] EWCA Civ 1357, in which a Christian registrar refused to carry out civil partnership duties because of her belief that such unions were contrary to God’s will. Again it was held that Ms Ladele had not been subjected to direct discrimination, indirect discrimination or harassment when she was disciplined for her refusal. The court held: “Ms Ladele’s proper and genuine desire to have her religious views relating to marriage respected should not... override the council’s concern to ensure that all its registrars manifest equal respect for the [gay] community as for the heterosexual community”.

Put to the test

Much for employment practitioners to consider, then, prior to lodging a tribunal claim based on the regulations:

- Do the claimant’s beliefs entitle them to the protection of the legislation?

- Can you show that philosophical beliefs are strong enough to be akin to religious beliefs?

- Will the claimant stand up to cross examination on whether their beliefs are genuinely held?

- Was the claimant’s religion or belief the actual reason for dismissal (or other action taken)?

- What is the correct way to formulate a claim (e.g. direct and/or indirect)?

- And have you considered the merits of any potential defence an employer may present to an indirect claim?

Jane Fraser, Head of Employment, Pensions and Benefits, Maclay Murray & Spens; convener, Employment Law Specialist Panel

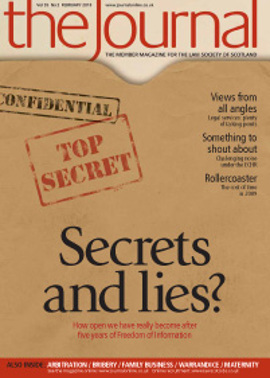

In this issue

- More prejudicial than probative?

- Another age

- Resolution is the key

- On the record

- Chequing out

- ABS workout

- Know your books

- Family business and business families

- Forum of choice?

- A right to silence?

- What does it mean to be a solicitor?

- Traineeships down over 25%

- Law reform update

- From the Brussels office

- Appreciation: Alfred Phillips

- Appreciation: John Sinclair

- Training for success

- From here... to maternity

- Ask Ash

- The move in-house - do you have what it takes?

- Big decisions

- Balancing exercise

- Belief boundaries

- Details, details, details

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Tougher regime

- No guarantees?

- Title insurance for insolvency practitioners

- PSG update