Details, details, details

Lawyers are often criticised for being overly concerned with detail and hampering progress, but the judgments in two recent pension cases show that years down the line, failure to pay attention to detail could come back to haunt those who rush ahead with a particular course of action. Both cases concern amendments to pension scheme benefits and highlight the importance of considering and complying with the terms of a scheme’s amendment power when making amendments.

Amending the amendment power

The first case, HR Trustees v German [2009] EWHC 2785 (Ch), involved so many different issues it would make an excellent case study for law students. In this case, a 1992 deed purported to change a scheme from providing final salary benefits to money purchase benefits. Prior to the conversion, members were given memoranda and a scheme booklet explaining the changes, a presentation and a membership application form. Later some of the members of the scheme were asked to sign compromise agreements waiving their rights to claim against the trustees in relation to the change.

The scheme was set up in 1977 by a deed containing an amendment power which was subject to a fetter or restriction providing that “no amendment shall have the effect of reducing the value of benefits secured by contributions already made” (the “original amendment power”). However, rules of the scheme were introduced in 1981 which contained a different amendment power with a less restrictive fetter.

The court considered a number of questions. Which amendment power applied? Was the 1992 deed effective in converting final salary benefits into money purchase benefits? Were members contractually bound by the changes or estopped from claiming they were effective?

The court held that the correct amendment power was the original amendment power contained in the 1977 deed, not the power in the 1981 rules, and therefore no amendment could be made which reduced the value of accrued final salary benefits. This did not mean that the 1992 deed was invalid, but an amendment could only be made with an underpin which preserved the future monetary value of the proportion of final pensionable salary which the member had accrued in respect of service before the date of execution of the amendment. The court also rejected arguments that even if the amendment was unlawful in terms of the trust deed and rules, members were contractually bound by the signed application forms, presentations and explanatory booklet. It was also not persuaded by arguments on estoppel (which is not dissimilar to our concept of personal bar) put forward by the company. And it held that the compromise agreements infringed s 91 of the Pensions Act 1995.

Actuarial advice

In the second case, Walker Morris Trustees v Masterton [2009] EWHC 1955 (Ch), the High Court held that various amendments were invalid even though this resulted in members’ benefits being scaled back. In this case the scheme’s amendment power contained a requirement that any amendment had to be the subject of written actuarial advice confirming that members’ benefits would not be prejudiced by the amendment.

Several amendments had been made to the scheme since 1981, most of which were benefit improvements in respect of which no actuarial advice had been sought. The question was therefore whether these amendments were valid?

The court held that the failure to obtain the written opinion of the actuary meant that the amendments were invalid. The court rejected the argument that a certificate issued by the actuary under s 67 of the Pensions Act 1995 would satisfy the opinion requirements, on the basis that it performs a different function to the written opinion required under the scheme’s amendment power.

Long term consequences

The German and Walker Morris cases show it pays for lawyers to be “details people”, because if there is insufficient attention to detail in the first place this can lead to difficulties much further down the line. These cases will also be of interest to the many employers who are considering ways to manage their pension scheme liabilities and risks: for example, closing the scheme to new members, or ceasing to allow members to accrue further benefits under the scheme, or amending the definition of “final pensionable salary”. They act as a stark reminder always to check the terms of the amendment power before making an amendment and to ensure its terms are fully complied with. If not, there is a risk the amendment could be held to be invalid and employers may find themselves having to fund benefits they were not expecting to have to pay for. Employers will also need to check that their compromise agreements are effective.

Katie Kerr is an associate with Biggart Bailllie LLP

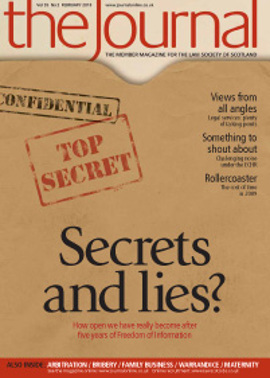

In this issue

- More prejudicial than probative?

- Another age

- Resolution is the key

- On the record

- Chequing out

- ABS workout

- Know your books

- Family business and business families

- Forum of choice?

- A right to silence?

- What does it mean to be a solicitor?

- Traineeships down over 25%

- Law reform update

- From the Brussels office

- Appreciation: Alfred Phillips

- Appreciation: John Sinclair

- Training for success

- From here... to maternity

- Ask Ash

- The move in-house - do you have what it takes?

- Big decisions

- Balancing exercise

- Belief boundaries

- Details, details, details

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Tougher regime

- No guarantees?

- Title insurance for insolvency practitioners

- PSG update