Tougher regime

The UK and Scotland’s bribery laws are due to be reformed to combat bribery in the private and public sectors and to ensure that the UK complies with international bribery conventions and treaties. The Scottish Government’s consultation Reforming the Law on Bribery and Corruption in Scotland recommended the adoption of similar laws to those proposed for England, Wales and Northern Ireland in the Bribery Bill. It is now anticipated that the Bribery Bill, which is expected to be enacted by June 2010, will be extended to apply to Scotland.

This article considers recent trends in corruption enforcement, the Bribery Bill and the steps that organisations should take to reduce the risk of corruption in their business dealings.

The need for reform

Transparency International’s Progress Report 2009 concluded that, as at the end of 2008, with four cases having been brought and approximately 20 active corruption investigations undertaken, the UK was only a “moderate” enforcer of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials. In contrast, Germany was considered to be an “active” enforcer, having brought over 150 cases in the same period.

Bribery enforcement

As a result of international criticism and pressure, there has been a considerable increase in the enforcement of the UK corruption laws since the end of 2008. This is mainly due to efforts of the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), the UK’s lead authority in relation to overseas corruption. The SFO and the City of London Police Economic Crime Unit have established dedicated anti-corruption units. About 25% of the SFO’s workload is in investigating corruption cases – the SFO is currently investigating £0.5 billion worth of bribes paid by British companies.

In September 2009, the engineering company Mabey & Johnson was the first British company to be convicted in the UK of offences of overseas corruption for seeking to influence decision makers in public contracts in Jamaica and Ghana between 1993 and 2001. Mabey & Johnson was fined £6.6m.

In addition, two major companies have been fined by the SFO in the form of civil recovery orders under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. The Financial Services Authority (FSA) has also been active in taking enforcement action against the insurance company AON for failing to properly manage the risk of bribes being paid by its overseas agents. AON was fined £5.25m.

In total, approximately £19m of fines have been imposed by the UK authorities in corruption cases since October 2008. Many more civil recovery cases are pending, as is the potential criminal prosecution of BAE Systems.

Self-reporting

In an attempt to increase the detection of overseas corruption and to give companies the opportunity to remedy corrupt practices, the SFO has published guidelines which state that it is prepared to use its civil recovery powers (instead of prosecuting) if companies self-report involvement in corruption.

There are, however, limitations to the SFO’s “leniency” policy. In particular, a company may not secure a civil settlement if its directors were party to, or benefited from, the paying of bribes. It is also important to note that the leniency policy only applies to companies incorporated in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service has not adopted a similar stance and there is not a leniency framework in place for Scotland.

The Bribery Bill

One of the main problems for the enforcement authorities, north and south of the border, is that the bribery and corruption laws are a patchwork of offences under the common law, the Public Bodies Corrupt Practices Act 1889, the Prevention of Corruption Act 1906 and the Prevention of Corruption Act 1916. There is no consistent definition of what amounts to bribery, the law is written in archaic language and is riddled with lacunas and anomalies. The Bribery Bill aims to change that by modernising and consolidating the bribery offences that can be committed by UK citizens and organisations, both in the UK and abroad.

The Bribery Bill will create five principal offences which can be committed by a British citizen, an individual ordinarily resident in the UK, or a body incorporated under the law of any part of the UK, even if the function or activity to which the bribe relates has no connection with the UK and is carried out in a foreign country.

1. Bribing another person

An offence will be committed if a briber offers, promises or gives a “financial or other advantage” to another person as an inducement or reward for performing improperly a function with which he is tasked by a public body, his employer, or a business or profession or another body. The performance of a function or activity will be “improper” if it is carried out in breach of an expectation that the person will perform a particular function or activity in good faith or impartially, or in breach of an expectation created by the fact that the person is in a position of trust.

A clear cut example of the giving of a bribe, and one that would likely lead to a prosecution if it came to light, is that of a property developer who offers £1,000 to a planning officer to approve the developer’s planning permission.

A less clear cut example, but one which could amount to bribery, depending on the circumstances, is that of a law firm that is tendering for work from company X offering a job or perhaps just a summer placement to the son or daughter of company X’s managing director. In that situation, one or more partners and indeed the firm might commit a bribery offence if it can be inferred the job was given to the son or daughter to induce the managing director to treat the firm favourably in the tender process.

2. Receiving a bribe

An offence will be committed if a person requests, agrees to receive, or receives a financial or other advantage as an inducement or reward for the improper performance, by himself or another person, of a public or business function that should be carried out in good faith, impartially, or in accordance with a position of trust. It is irrelevant whether the recipient requests, agrees to receive or receives the advantage directly or through a third party, or whether the bribe is for the benefit of a third party.

3. Bribery of foreign public officials

There is a distinct offence of bribing foreign public officials. A “foreign public official” includes anyone holding legislative, administrative or judicial posts and anyone carrying out a public function for a foreign country or the country’s public agencies.

The offence will be committed if a person, directly or through a third party, offers, promises or gives any financial or other advantage to a foreign public official, which is not legitimately due, with the intention to influence the official in connection with obtaining or retaining business or an advantage in the conduct of business. The offence will also be committed if the advantage is offered to someone other than the official, if that happens at the official’s request.

The advantage will be legitimately due only if the law applicable to the foreign public official permits or requires the official to accept the advantage. It is therefore not a defence that an advantage is customary or tolerated. Unlike the other bribery offences, this offence does not require the action expected in return to be improper. This means that relatively modest corporate entertainment of foreign public officials could amount to a criminal offence if the corporate hospitality was intended to win or retain business, unless the local law expressly allowed the giving of corporate hospitality to public officials.

4. Failure of commercial organisations to prevent corruption

Commercial organisations will commit an offence if they negligently fail to prevent a person performing services on their behalf from paying or offering a bribe.

A person performing services on an organisation’s behalf could include employees, agents, subcontractors and joint venture partners.

A significant risk is posed by individuals or companies contracted to provide support and advice on marketing, sales and procurement in other countries. Agents are often paid or incentivised by commission payments on the award of work or a contract. Commission payments can provide an agent with the means and motive to obtain contracts by paying bribes.

It will be a defence for the commercial organisation to show that it had “adequate procedures” in place to prevent bribery being committed on its behalf, unless a director or senior manager was negligent. A company should not therefore be liable for a failure to prevent bribery, on the basis of a single instance of carelessness by lower level employees, if it can show that it had robust management systems in place to prevent bribery.

What amounts to “adequate procedures” will depend on the size and resources of the company in question. In a small company with five employees, it might be perfectly adequate for the managing director to simply remind the employees (and others) periodically of their obligations, whereas with larger companies, detailed compliance procedures will be required to satisfy the “adequate procedures” defence.

5. Personal liability of senior officers

A director or senior manager who consents to or connives in the giving or receiving of bribes by a company also commits an offence. So, for example, the company would commit an offence if the managing director authorised the payment of a bribe, as would the managing director personally and any other director who turned a blind eye to the irregular payment.

Prepare in advance

The Bribery Bill will inevitably lead to an increase in corruption investigations, civil recovery orders and prosecutions for corruption. In particular, it will be significantly easier to prosecute businesses as there will effectively be a strict liability offence, subject to an adequate procedures defence, of failure to prevent bribes being paid in connection with the organisation’s business. It would therefore be advisable for all organisations to conduct anti-corruption risk assessments, and put in place “adequate procedures” designed to prevent corruption in advance of the Bribery Bill coming into force.

Tom Stocker, Partner, Business Crime and Commercial Fraud, McGrigors LLP

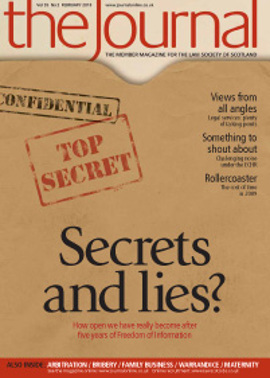

In this issue

- More prejudicial than probative?

- Another age

- Resolution is the key

- On the record

- Chequing out

- ABS workout

- Know your books

- Family business and business families

- Forum of choice?

- A right to silence?

- What does it mean to be a solicitor?

- Traineeships down over 25%

- Law reform update

- From the Brussels office

- Appreciation: Alfred Phillips

- Appreciation: John Sinclair

- Training for success

- From here... to maternity

- Ask Ash

- The move in-house - do you have what it takes?

- Big decisions

- Balancing exercise

- Belief boundaries

- Details, details, details

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Tougher regime

- No guarantees?

- Title insurance for insolvency practitioners

- PSG update