Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose

(The more things change, the more they stay the same: Alphonse Karr, Les Guêpes, 1849)

The last decade has seen a tornado of radical reform blow through the corridors of Scots law, carrying with it promises of consistency, clarity, transparency, accountability, safety and protection for the vulnerable.

In particular, there have been several significant pieces of legislation which dramatically altered the legal landscape for women, children and young people experiencing domestic abuse, and brought with them the promise of increased safety and protection.

Leading the way came the Protection from Abuse (Scotland) Act 2001, the first committee bill of the then new Scottish Parliament, which widened the availability of interdicts with a power of arrest, allowing thousands of women who, hitherto, had been excluded from this protection, to access these important orders.

This was followed by reforms to the criminal law allowing police to arrest for breach of a non-harassment order without a warrant. Recognising that supporting witnesses to deliver their best evidence also supported their engagement with, and therefore the processes of, Scots law, all witnesses in both civil and criminal proceedings were provided with a procedure to access this support and protection.

Ensuring the safety and protection of children experiencing domestic abuse, particularly in relation to proceedings for contact and residence, was rightly seen as an issue requiring urgent attention. This was reflected in the provisions of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006, whereby the court was specifically required to address the issue of domestic abuse when considering matters relating to the welfare of the child.

To the casual observer, this array of enlightened thinking and positive action suggests that the day-to-day lives of women experiencing domestic abuse have been made substantially safer, and their engagement with, and experience of, the civil and criminal justice systems radically improved.

Unfortunately, this is not the case. The special measures provided by the vulnerable witnesses legislation are not routinely accessed, particularly in civil actions, and women are being misinformed about their availability; dangerous and violent offenders are routinely given bail or released on licence and are able to stalk, monitor and harass women from prison via telephone and the mail; contact with and/or residence of children is routinely awarded to perpetrators of abuse, despite it being inappropriate, of no benefit to the child and often a clear safety risk to the child and non-abusing parent.

Reforms to the system of payment of civil legal aid fees to solicitors have actually resulted in a worsening of the position for women experiencing domestic abuse. A consequence has been that the pool of solicitors previously offering civil legal aid-funded services has dramatically reduced, particularly those prepared to carry out work in relation to obtaining protective orders.

It appears that, despite these very necessary changes being implemented at a policy and strategic level, they are not being translated into action at the important, practical level where they can make a difference to women’s and children’s lives.

For us, the saddest and most damaging example of this failure to act is the apparent ambivalence directed towards the provisions on the welfare of the child contained within the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006. It is widely known, and accepted, that the existence of domestic abuse in the context of child contact and residence proves a significant risk of continuing harm and abuse to the child, and the mother.

In recognition of this, both the Scottish Government and Scottish Parliament accepted that the existing legislation should be strengthened by having domestic abuse highlighted as a matter which the court was specifically required to consider and comment on in these cases. The relevant amendments to the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 were enacted in the 2006 Act.

Despite this, women are still contacting us in despair because the legislation is simply not being used. Courts still appear to consider that the concept of children having contact with both parents at all costs should continue to override the safety and welfare of the child, and women have been counselled not to tell the court about domestic abuse.

When policymakers and legislators heed public opinion and the pleas of the most vulnerable members of our society on the need for change, and the necessity of righting a wrong, it is the moral and legal duty of all who come under the auspices of these reforms to use their best endeavours to implement them, putting any other considerations or views aside.

In not doing so, we present a picture of a remote and distant system that apparently ignores the needs of those using it and does not connect with them.

The result is a lack of confidence in the system on the part of those women, children and young people whom it should be supporting and protecting, and for those who present a danger to them, licence to act and behave as they choose.

In this issue

- Islamic law - the beginnings

- Depriving criminals of their ill-gotten gains: is it happening?

- Burdening the legal aid lawyer

- Landlord's hypothec: the permutations

- Time to push for Gill

- Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose

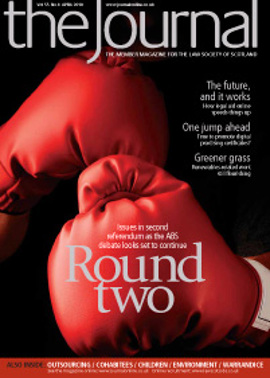

- Seconds out

- Help at hand

- Win-win situation

- Giving and taking away

- Home and away

- Quest for power

- A crumbling monument?

- No happy ending

- Seminars target money laundering awareness

- DP/FOI specialism opens to applicants

- Law reform update

- Points of access

- Diploma or not?

- From the Brussels Office

- Are you who you say you are?

- Ask Ash

- Social media: a revolution

- A commercial approach

- Growth industry

- Price of success

- Variations: some more thoughts

- Tenancy or bust

- Another nibble of the cherry

- Planning with add-ons

- Website review

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Book reviews

- It's never too early to call your external solicitor?

- Dereliction of duty?

- To grant or not to grant?