No second chance

Desertion pro loco by the court

Once a trial is underway, a court should only desert the diet pro loco et tempore in exceptional circumstances: Parracho v HM Advocate [2011] HCJAC 11 (9 February 2011) makes this very clear. There, a bench of five judges refused an appeal where the appellant had been tried twice: his first trial was deserted pro loco on Crown motion during the hearing of a defence submission of no case to answer, while the second trial, which had commenced immediately thereafter, resulted in a conviction.

Crucially, it was an appeal against that conviction which brought the original decision to desert under appeal court scrutiny: although there had been no prior attempt to bring a bill of advocation against that decision, it was now said that the Crown should not have been given the opportunity of “starting again”.

The stated reason for desertion of the original diet was an error on the part of the Crown by failing to lead evidence that a DNA sample analysed by forensic scientists was that of the accused. It appeared that it was intended that the necessary evidential link would be covered by a joint minute, but this had been overlooked. The trial judge noticed this during the “no case” submission; ultimately a decision to desert was taken and a further diet on the same indictment was ordered.

The appeal court did not support the decision to desert, holding that where the difficulty which has arisen is the omission by the Crown timeously to lead evidence on which it intends to found, desertion would circumvent the rule that the Crown must lead all its evidence before closing its case. What should have happened was that the trial should have proceeded; the Crown’s position was that even without the DNA link, there was sufficient evidence in law. Having examined that evidence, the court agreed and rejected a submission that there had been a miscarriage of justice. While it was correct that the appellant had not been able to go to the jury on the restricted evidential basis (as was his intention had the submission been concluded and refused), he had had an opportunity to advocate the decision to desert at the time it was made.

The plea of diminished responsibility

When ss 168 to 171 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 are brought into force, one hitherto unresolved issue as to the scope of a plea of diminished responsibility will be addressed: does the plea only apply in cases of murder? The new law will expressly restrict its scope to such cases, but what of the position until then? There is a conflicting line of authority on the point, but in relation to a charge of attempted murder, it appears from HM Advocate v Kerr [2011] HCJAC 17 (24 February 2011) that the plea is open meantime.

The case came before the appeal court at the instance of the Crown, which had appealed against a ruling made at a preliminary hearing to reject its argument to the contrary effect. It was said that mitigation of penalty because of the state of mind of the accused could be achieved without recourse to the plea in all cases except that of murder, where the penalty was fixed by law. In murder cases the only way to achieve such mitigation was to reduce the crime to culpable homicide by reason of diminished responsibility, and that was as far as the law should go. For the accused, the argument centred on the overlap between the plea of provocation and that of diminished responsibility; in cases where provocation was alleged, a jury could not reach a conclusion about the commission of the crime of murder without considering the question of provocation; a similar approach was appropriate in cases involving allegations of murder or attempted murder where diminished responsibility was in issue.

The court was persuaded that the approach of Lord Brand in HM Advocate v Blake 1986 SLT 661 had been correct. That was a case of attempted murder, where the jury had been directed that the effect of diminished responsibility was to reduce the charge to the crime of assault. There was nothing unjust or illogical in such a conclusion, nor any justification in principle or practice for distinguishing between someone whose responsibility was diminished by reason of some mental abnormality and someone whose culpability was reduced by reason of provocation. The Crown appeal was refused.

Money laundering defences

Prosecutions for money laundering are relatively uncommon in Scotland, but one such case has now come to its conclusion. On 25 February 2011 the appeal court made available its reasons for refusing the appeal in Ahmad v HM Advocate [2011] HCJAC 21, which had been heard a few weeks previously. The appellant had been convicted inter alia of an offence under s 330(1) of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, which (broadly) covers the situation where someone fails to disclose to the authorities either knowledge, suspicion or reasonable grounds for suspicion that a person is involved in money laundering, where that knowledge or suspicion came to him in the course of a business in the regulated sector.

One of the defences to such a charge arises under s 330(6) and (7) of the 2002 Act: if the accused does not know or suspect that the other person is engaged in money laundering and he has not been provided by his employer with such training as is specified by the Secretary of State by order for the purposes of that section. In Ahmad the appeal court provided a useful clarification of how this defence operates.

Specifically, it rejected an argument that these subsections had been put in issue in the case because there was evidence that an officer of HM Revenue & Customs had met with the appellant at his business premises for a compliance visit. At the meeting the discussion covered many aspects of the anti-money laundering regime, and the question of “training” had been mentioned. This, said the court, was an insufficient basis for suggesting that the Crown had required to exclude the operation of the subsections: the evidence had not been led for that purpose; it did not even accidentally put the requirement of the subsections in issue; there had been no cross-examination in relation to the provision of training; and the issue was not focused during the evidence or in counsel’s speech to the jury. In these circumstances the trial judge did not require to give the jury any directions on the matter, although he had done so; there had been no miscarriage of justice.

Discretionary life and punishment parts

The decision of seven judges in Petch and Foye v HM Advocate [2011] HCJAC 20 (1 March 2011) is so long (60 pages), raises so many issues, and discloses so much divergence of judicial opinion, that this column is not the place for a full analysis. The most that can be attempted here is to note the ongoing controversy. Petch had been sentenced to life imprisonment for raping two children, while Foye had received an order for lifelong restriction (“OLR”) for the assault and rape of a 16 year old girl. What was in issue in the appeal was the appropriate length of the punishment part of each sentence, a matter which turns on the proper interpretation of s 2(2) of the Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993, as amended. This requires the court in such cases to fix a period of time which it considers appropriate to satisfy the requirements of retribution and deterrence (ignoring any period which may be necessary for the protection of the public), which the prisoner must serve before the question of parole can be considered.

Exactly what steps require to be taken by a sentencer in computing the punishment part in cases of discretionary life or an OLR, having regard to the statutory language of

s 2? A number of specified matters have to be looked at in fixing the period, and this is where difficulty has arisen and indeed continues. As well as taking into account under subs (2)(a) the seriousness of the offence, the court must assess under subs (2)(aa)(i) what notional determinate sentence would have been imposed had life or an OLR not been selected; assess what part of that period would satisfy the requirements of retribution and deterrence, ignoring the element of public protection; and assess under subs (2)(aa)(iii) the proportion of that part which a prisoner sentenced to it would or might serve before being released, either on licence or unconditionally.

How to do all of this led to a disagreement between the five judges in Ansari v HM Advocate 2003 JC 105, with Lord Reed dissenting from the view of his colleagues; and it was his view which found favour with the majority of the court in the instant appeal. They thought inter alia that the court should not consider the manner in which the Parole Board deals with such cases, and that the exercise required by s 2(2)(aa)(iii) of the 1993 Act involved taking into account half of the notional sentence, the seriousness of the offence having already been taken into account under subs (2)(a) and (2)(aa)(i). But a variety of disagreements on this and related points among the other judges led the Lord Justice General and certain of his colleagues to suggest that a clear legislative solution was now called for. As for the appeals, they were remitted to a bench of three judges for disposal in light of the views expressed in the judgment of the court and other relevant considerations.

In this issue

- Civil legal aid in the supreme courts

- Ever-eventful year

- Coming out - on top

- In the awards

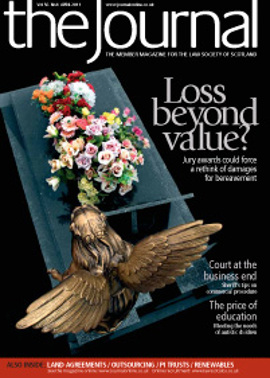

- The price of grief

- Commercially driven

- Autism and the good society

- Guardians of the PIT

- Arbitration outreach

- The cloud? It's down to earth...

- Searching for a constitution

- Complaints update: disclosing information

- Dean waives cab rank rule in civil legal aid cases

- Law reform update

- The learning curve

- Legal services outsourcing: don't miss the boat

- Ask Ash

- The right steer

- No second chance

- Burning a hole in the law

- Protecting the prescribed part

- Final brick in place

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Stretching the public purse

- Land and the open market

- Easing the burdens?

- It's an ill wind...