E for explanation

The decision of the Supreme Court reported as E (Children) [2011] UKSC 27 (10 June 2011; hereafter “E”) has come as something of a relief to family practitioners dealing with Hague child abduction cases. E deals with the difficulties that had arisen following the European Court of Human Rights Grand Chamber decision in Neulinger and Shuruk v Switzerland (Application no 41615/07), 6 July 2010.

It had been suggested that Neulinger undermined the effective operation of the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction of 25 October 1980, at least in the 47 states that have ratified the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms: the ECHR. Neulinger, it was said, now required our courts to undertake a “full-blown examination of the child’s future in the requested state” (E at para 22), rather than continuing to deal with applications in a summary and swift manner.

Neulinger had already reared its head before our courts, and the decision in E (the bench of five judges included Lord Hope) is to be welcomed. Neulinger had created waves when it said (at para 139) that “the court must ascertain whether the domestic courts conducted an in-depth examination of the entire family situation and of a whole series of factors, in particular of a factual, emotional, psychological, material and medical nature, and made a balanced and reasonable assessment of the respective interests of each person, with a constant concern for determining what the best solution would be for the abducted child in the context of an application for his return to his country of origin”. The issue was what this meant in practice for our courts.

Best interests still first

E was a standard Hague case involving four and seven-year-old girls who had been taken by their mother from Norway. She argued the article 13(b) “grave risk” defence. The case had been heard in the lower courts and then the Court of Appeal before permission to appeal to the Supreme Court was granted, specifically because there was thought to be a need for guidance on the significance of Neulinger.

The Supreme Court made clear that, although there is no express provision requiring the court dealing with a Hague case to make the child’s best interests its primary consideration, that “does not mean that they are not at the forefront of the whole exercise” (para 14). The court concluded that both the Hague Convention, and indeed Brussels II revised, were “devised with the best interests of children generally, and of the individual children involved in such proceedings, as a primary consideration” (para 18).

Criticism of the “full-blown examination” approach advocated in Neulinger had been made in E as it made its way through the lower courts. Interestingly (for the law geeks among us), the opinion makes reference to extrajudicial comments made by the President of the Strasbourg court in response to concerns about how Neulinger was being interpreted, and refers, inter alia, to the subsequent acknowledgment by the President that Neulinger “does not therefore signal a change of direction at Strasbourg in the area of child abduction” (para 25).

Compatible practice

So where do Neulinger and E leave us at a practical level? To a large extent it is business as usual: the writer’s view is that the current practice and procedure of the Scottish courts in child abduction cases – which focuses on a “summary and swift” approach – follows the approach advocated by the Supreme Court in E. It was made clear that there is still scope for the manner in which child abduction cases are dealt with to fall foul of the ECHR: there are some interesting possibilities left hanging in para 27 of the judgment contemplating ECHR incompatibility where a court, as a public authority, orders return in a situation where the parent returning with the child (where the child cannot safely be returned without them) faces “a real risk of torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment or the flagrant denial of a fair trial”.

There may still be some scope to get a little more “colour” in your response to the petition as a result of Neulinger, but don’t expect the Scottish courts now to start undertaking the exercise of identifying with whom the child should be living. As long as the court does not try and order return “automatically and mechanically” (E at para 26), and that it is borne in mind that there remains a need for an examination of the child’s circumstances (which, it was said expressly, was “not the same as a full-blown examination of the child’s future”), there should not be any need for change as a result of E or Neulinger.

In this issue

- Employee ownership: untapped succession solution for legal firms

- Cash call: cornering the council tax

- Tobacco Act sound

- Public profile

- Too much heat, not enough light

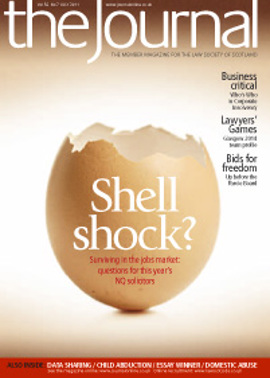

- Newly hatched

- Money matters

- Families in fear

- Get out of jail?

- People's choice

- E for explanation

- Who's Who in Corporate Insolvency

- Care with sensitive case papers

- Bullying: time to crack down

- SYLA reports successful year

- Middle East: back to growth

- Sheriff court auditor role to be restricted

- Law reform update

- From the Brussels office

- Solicitor's guide to internet porn

- Ask Ash

- Data sharing – the good practice guide

- Legal Risks – a conference reviewed

- Long-term solutions

- Removing hardship?

- 18 or 21?

- Lenders in the shade

- Demolition derby

- Time to come clean

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Going the distance

- Fashion retailing comes to court