People's choice

I believe that the Scottish Law Commission’s Report on Succession from April 20091 should be taken forward for implementation. The report deals mainly with intestate succession and cohabitants. This is an appropriate area for reform as there are many problems with the current system. Intestate succession is of interest to voters as roughly only one-third of the Scottish population have a will.2 The present law on succession for cohabitants has proven unclear, as it is reliant on the court’s discretion. This essay shall suggest three main areas of reform: the prior rights of a surviving spouse, legal rights, and cohabitants.

The current law in regard to intestate succession is governed by the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964 and the Prior Rights of Surviving Spouse (Scotland) Order 2005. After debts, the prior rights of the surviving spouse3 of the deceased are the next obligation that must be met. However, this area of law has many problems.

Prior rights made simple

The prior rights are divided into the prior right to a dwellinghouse,4 prior right to furniture and plenishings,5 and the prior monetary right.6 In order to claim these rights, the property in the estate and the spouse must meet the criteria within the Act. This means the rights of a surviving spouse are property-specific, and so they are complicated and do not readily apply to all estates. For example, in order for a spouse to have a prior right to the dwellinghouse and furniture and plenishings, they must have been ordinarily resident at the house.7 This may cause unfairness in situations where the surviving spouse had left the home to get away from an abusive partner.

The current maximum value of prior rights is £399,000,8 as the maximum value of the dwellinghouse is £300,000, furniture and plenishings is £24,000 and (if there are no issue) the maximum monetary sum is £75,000. In the report the Commission proposes that this system be replaced with the spouse getting the entire net intestate estate if there are no issue.9 If there are issue then it is proposed that the spouse should have a right in the estate up to a threshold sum, and to the whole estate if it amounts to less than the threshold sum.10 This sum would be non-property specific and thus solve the problems created by prior rights.

In order for this to be effective in protecting the spouse, the threshold sum must represent the average house price to ensure that, in most cases, the spouse may continue to reside in the family home. The monetary sum was previously paid pro rata from moveable and heritable property, which complicated the calculation. The proposals make no distinction between moveable and heritable property, which should simplify this.11 The Commission proposes the sum to be set at £300,000, but states that it feels this is a political decision and it is up to the Scottish Ministers to decide what the appropriate sum would be. In 2007, only 2% of confirmed estates were over £300,000,12 so this would cover most spouses entirely.

The only possible problem with this is where there is a survivorship destination clause in favour of the surviving spouse for the family home, so that the home passes immediately to the surviving spouse on the other’s death without becoming part of the deceased’s estate.13 In this situation the Commission proposes that the value of the property subject to the clause should be taken into account in the threshold sum.14

More problematic are cases where the property exceeds £300,000 but is now the surviving spouse’s and they cannot be made to forfeit it. For this situation, the Commission proposes that the amount over £300,000 be deducted from the value of the intestate estate and the surviving spouse be entitled to half of that remainder.15 This would entitle the spouse to a considerable capital sum if the value of the house is just above the threshold, but also ensures that where the spouse inherits a very valuable property, their right to other assets diminishes accordingly, so large estates may still provide large legal shares to offspring. As 42% of homes in Scotland are jointly owned and about three-quarters of these are subject to survivorship destination clauses,16 this is clearly an important practical consideration.

Legal rights: popular choice

The issue of legal rights is also significant. It is important to note that these rights may be claimed even where there is a will disinheriting the spouse or issue. The legal rights of the spouse will be dealt with first.

Currently, the surviving spouse has a right to one-third of the net moveable estate if there are issue and one-half if there are not. This is problematic where the estate is mainly made up of heritable property.

There is much support for protecting the spouse from disinheritance.17 Thus the Commission proposes that legal rights are replaced with a legal share of 25% of the whole of the deceased’s net estate,18 to solve the problem where the property is mainly heritage.

Issue of the deceased also have a legal right to one-third of the net moveable estate if there is a spouse, and one-half if there is no spouse. The Commission believes that legitim for children should be abolished and not replaced. Instead, on death, children under 25 should be given a capital sum calculated on the basis of what is required to maintain the child until they are no longer dependent (attain the age of 25).

There are many arguments in favour of abolishing legitim. For example, the obligation to aliment ends at 18 (or 25 if in education),19 so it is unclear why adult children should be entitled to their parents’ money. Most people are middle-aged when their parents die, and have their own money. In any case, few actually inherit substantial sums. Legitim also seriously limits the freedom to test. Another argument against legitim is that it was conceived partly as a way of “compensating” children for taking care of their parents in old age, yet in recent times most of the obligation to care for the aged now rests on the state, not their children.

However, in the 2005 Succession Opinion Survey, 70% of people still thought that adult children should have a claim on their parent’s estate if left out of their will. Ideas such as keeping wealth in the family and the existence of a moral duty to support children throughout their life obviously still hold sway in public opinion. Therefore, the Commission proposes either a 25% legal share, or a capital payment based on the level of dependency the child has on the parent immediately before death, but suggests the 25% share would be less problematic.20 This share would be from the entire estate, not just moveable property, and thus would solve the problem of estates made up largely of heritable property.

Cohabitants: new guidelines

Succession between cohabiting couples is a third area for reform. Prior to 2006, there was no protection for cohabitees whose partner died intestate, but the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006, s 29 allows them to apply to the court for payment out of an intestate estate within six months of the death. They may receive a transfer of property and/or a capital sum.

In deciding whether or not to grant this, the court will consider the size and nature of the deceased’s net intestate estate, any benefit the cohabitee has already received, the nature and extent of rights and claims on net intestate estate, and any other matter the court thinks appropriate.21

This was a response to the 2005 Succession Opinion Survey in which 80% favoured cohabitants having rights where their partner dies intestate. However, there are several problems with s 29. The discretion given to the court has led to some relatively unfair decisions, as there is no guidance given to the court as to what is relevant.

In the case of Savage v Purches,22 a couple cohabited for two and a half years and the deceased used to treat his partner to expensive things. He died intestate with no children; under intestate law the deceased’s sister was entitled to inherit the estate. Savage claimed for a capital sum of £400,000, but this was refused as he had already received £124,000 from the pension fund of the deceased, had benefited substantially throughout their cohabitation – they only lived together for a relatively short period – and the deceased had not made provision for him in a will.

This decision did not take account of Savage’s dependence on the deceased, and it is unclear why the benefits received during the deceased’s life were given so much weight.

The six-month time limit for raising a claim is too short and can cause problems. There has been at least one case where a cohabitant has been time-barred through no fault of her own. The deceased had made a will under which his cohabitant was the major beneficiary, but the deceased’s relatives challenged the will. Their action was successful and the will was reduced. While the estate was rendered intestate, the surviving cohabitant could not bring a claim under s 29, because the six months had expired.

The Commission proposed that s 29 be replaced with five new factors:

- whether or not the parties were members of the same household;

- the stability of the relationship;

- whether or not there was a sexual relationship;

- whether or not there are children; and

- whether they appeared to third parties as if they were married.23

The Commission also recommends that when fixing the percentage sum, the court should consider the length of the cohabitation, the couple’s interdependence, and the contributions to the running of the household.24 Finally, the Commission suggests that the time limit for making a claim be extended from six months to a year.25

By giving definite factors for consideration, this mitigates problems created by the open-ended discretion, allowing the court to consider any factor it thinks appropriate. It also prevents the court putting too much emphasis on the amount of money in the estate and not the couple’s relationship, as the court will not be privy to the extent of the estate.

Nevertheless, these proposals still leave the court with much discretion and do not give guidance as to the weight of each of these factors. Cohabitees must continue to go through the inconvenience and expense of raising a court action, which will deter those who do not think they will inherit much or where there are hostile relatives of the deceased. The Commission rejects the view that cohabitants should have an automatic right to inherit,26 but with an increasing number of people choosing to cohabit,27 this may prove problematic in the future.

In conclusion, the Law Commission’s Report on Succession should be implemented as the current law is much in need of reform. By implementing the report, most spouses would inherit all of the deceased’s estate, legal rights would be replaced by a legal share which would allow the spouse and children to receive a much larger portion where the estate is mostly heritable, and the factors considered by the court when deciding a claim by cohabitants would better reflect the couple’s relationship. All of these objectives have proven to be popular with the public and thus should not be too controversial to implement.

References

1 Scot Law Com no 215: www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/law-reform-projects/completed-projects/succession/

2 Research found that only 37% of Scots had made a will, but that this increased to 69% of those aged 65 or over: S O’Neill, Wills and Awareness of Inheritance Rights, Scottish Consumer Council (2006), p 5 n 40.

3 The use of the term “spouse” shall mean there are equivalent rights for a civil partner under the Civil Partnership Act 2004.

4 s 8(1) of the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964.

5 s 8(3) of the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964.

6 s 9 of the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964.

7 s 8(4) of the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964.

8 Sched 1 to the Prior Rights of Surviving Spouse (Scotland) Order 2005.

9 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 2(2), found at p 23 of the Report on Succession.

10 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 2(3), found at p 27 of the Report on Succession.

11 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 2(3), found at p 27 of the Report on Succession.

12 D Reid, “From the Cradle to the Grave: Politics, Families and Inheritance Law” (2008) 12 Edinburgh Law Review 391 at p 414.

13 s 36(2)(a) of the Succession (Scotland) Act 1964 .

14 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 3(3), found at p 30 of the Report on Succession.

15 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 3(4), found at p 31 of the Report on Succession.

16 These statistics have been acquired from Registers of Scotland based on a sampling exercise of six titles in each of 23 out of the 33 registration counties.

17 Scottish Law Commission Report on Succession, p 43, para 3.4.

18 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, ss 11 and 15, found at p 44 of the Report on Succession.

19 Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985, s 1(1) and (5).

20 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, ss 12 and 13(3), found at p 56 of the Report on Succession.

21 s 29(3) of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006.

22 2009 SLT (Sh Ct) 36.

23 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 22, found at p 138 of the Report on Succession.

24 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 23(1) and (2), found at p 138 of the Report on Succession.

25 Scottish Law Commission Draft Bill, s 23 (3), found at p 139 of the Report on Succession.

26 p 80 of the Report on Succession 2009 (no 215).

27 20% of people in Scotland were cohabiting in 2000-2002: www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE/ssdataset.asp?vlnk=7677

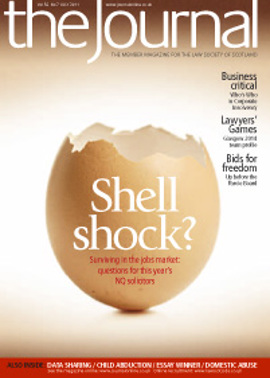

In this issue

- Employee ownership: untapped succession solution for legal firms

- Cash call: cornering the council tax

- Tobacco Act sound

- Public profile

- Too much heat, not enough light

- Newly hatched

- Money matters

- Families in fear

- Get out of jail?

- People's choice

- E for explanation

- Who's Who in Corporate Insolvency

- Care with sensitive case papers

- Bullying: time to crack down

- SYLA reports successful year

- Middle East: back to growth

- Sheriff court auditor role to be restricted

- Law reform update

- From the Brussels office

- Solicitor's guide to internet porn

- Ask Ash

- Data sharing – the good practice guide

- Legal Risks – a conference reviewed

- Long-term solutions

- Removing hardship?

- 18 or 21?

- Lenders in the shade

- Demolition derby

- Time to come clean

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Website review

- Book reviews

- Going the distance

- Fashion retailing comes to court