Don't drag out child cases

In M v M [2011] CSIH 65 (12 October 2011) a father appealed a decision to allow his estranged wife to take their children to England. The facts are, of course, particular to the case itself. The matters I would bring to readers’ attention are the Inner House’s observations regarding appeals in cases involving children.

Their Lordships reiterated the observations by Lord Fraser in G v G [1985] 1 WLR 647 that an appellate court should only intervene if there was so blatant an error on the part of the judge at first instance that it could only have been reached as a result of an error in the method used to reach that decision. Disagreement with the decision was not in itself enough.

The only other basis for interference was a disclosed inclusion of irrelevant or exclusion of relevant matters. They further reiterated Lord Hope’s observations in Sanderson v McManus 1997 SC(HL) 55 to the effect that due to the passage of time involved in appeals, such a step was generally unsatisfactory as there was likely to have occurred a change in circumstances. As a result, while allowing the appeal, the Inner House remitted the matter back to a sheriff to consider a renewed application by either parent against the background of updated evidence. It further observed that in such cases it was important that a sheriff made findings on all potentially important issues.

Here there were no findings regarding the possibility of ongoing contact and the transfer of the children from one school to another. (This decision overturns that of Sheriff Principal Bowen, reported at 2011 SLT (Sh Ct) 170.)

Permanence orders

Midlothian Council, Petitioners, Edinburgh Sheriff Court, 29 August 2011, an application for a permanence order, required Sheriff Holligan to consider the issue of jurisdiction. By s 118(2) of the Adoption (Scotland) Act 2007, the appropriate sheriff court is the court “within which the child is” when the application is made. The child had been born in Edinburgh but within four days had been placed with foster parents in Clydebank. She had lived there for almost a year before the application was lodged. A literal interpretation was held inappropriate. The decision was one of fact to be made against all the surrounding facts and circumstances. Sheriff Holligan concluded that Edinburgh Sheriff Court was not the appropriate sheriff court.

The petitioners’ fallback position was that if Edinburgh Sheriff Court did not have jurisdiction, the matter should be remitted to the Court of Session. Sheriff Holligan agreed to this application. In disputes regarding children, rules of procedure should be construed having regard to the welfare and interests of the child. Section 37(2A) of the Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1971 left the question of remit in family actions, adoptions and the like to the sheriff’s discretion. If the action was dismissed through want of jurisdiction, this would simply result in delay. There were matters in this application which could result in guidance being given by the Court of Session.

Diligence on the dependence

In Bain v Rangers Football Club [2011] CSOH 158 (23 September 2011), Lord Hodge granted an application for arrestment on the dependence. On the information before him, his Lordship considered that there was a real and substantial risk of the defenders’ insolvency.

He further considered that the diligence was reasonable, although the main factor which caused there to be such a risk had occurred during the pursuer’s employment as chief executive.

In Hughes v Hughes, Dumfries Sheriff Court, 19 August 2011, warrant to execute diligence on the dependence of a financial claim in a divorce was upheld on appeal, where the sale of a house was averred to have taken place to defeat that claim and without the diligence there was a danger that that aim would be achieved.

Dismissal following delay

A plea of inordinate and inexcusable delay was upheld in Hardie v Morrison and Ferris, Kirkcaldy Sheriff Court, 5 October 2011. The action had been raised in late 2000 and then sisted in early 2001. No further procedure had taken place until May 2011. The pursuer had not been active during the sist. Sheriff McCulloch considered that the delay was inordinate and unexplained. Due to a number of factors he considered that prejudice would result. These included significant procedural consequences in allowing the action to continue, diminution of witness recall, and destruction of paperwork.

Interim interdict

Appellants in Cowie v Martalo 2011 GWD 32-676 challenged the competency of an order for interim interdict against diligence to enforce the obligation of a lease registered for preservation and execution, the issue of caution in terms of the Act of Sederunt (Summary Suspension) 1993 having not been addressed. A charge had been served to enforce the obligation and the interdict was taken against further diligence. Sheriff Principal Lockhart agreed that the issue of caution should have been considered either when interim interdict was granted or shortly thereafter.

Judicial interest

The applicable rate of interest over a period when the judicial rate was greater than market rates was argued before Lord Hodge in Farstad Supply AS v Enviroco Ltd [2011] CSOH 153; 2011 GWD 32-682. His Lordship decided that the judicial rate was often above the return obtainable on deposited funds. However, the purpose of the judicial rate was to compensate an innocent party for the involuntary use of funds to cover a loss caused by the actions of another. Account could be taken of such differences in interest rates in the period between the loss and decree by reducing the rate of interest applicable, albeit judicial interest was simple and not compound, and large commercial concerns might be able to achieve preferable rates of interest.

Post-decree, the judicial rate was appropriate even if it might be considered mildly penal, as it encouraged implementation of the court’s decision which ascertained the true measure of loss: any pre-decree uncertainty as to the extent of loss no longer applied.

Actions for reduction

In Royal Bank of Scotland v Matheson [2011] CSOH 154 Lord Glennie considered that the test for whether a decree in absence should be reduced was less strict than that which applied to decrees in foro: it involved considering whether there was an arguable defence, but there was no requirement to establish exceptional circumstances, the court exercising its discretion in light of all the circumstances.

Damages and human rights

In Docherty v Scottish Ministers; Philbin v Scottish Ministers; Logan v Scottish Ministers [2011] CSIH 58 (2 September 2011), the Inner House indicated that where prisoners were suing for damages arising from custodial arrangements made by the defenders which allegedly breached articles 3 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, such actions could competently be pursued as ordinary actions for damages.

Division and sale

In Maclure v Stewart, Peterhead Sheriff Court, 13 September 2011, Sheriff Mann refused to grant decree for vacant possession and warrant for ejection when presented with a minute for decree in absence in an action for division and sale. The pursuer was a pro indiviso proprietor, albeit as a trustee in bankruptcy. Until such time as an order for sale was implemented, the pro indiviso proprietors retained their rights of ownership, which included a right to occupy. Neither proprietor had a greater right than the other and thus one could not eject the other.

Discharge of bankrupt

Sheriff Holligan had to consider an application for a deferment of a bankrupt’s discharge in Allan Anthony Campbell, Edinburgh Sheriff Court, 7 September 2011.

The sheriff noted that there was no statutory guidance as to the basis on which such an application might be made or decided. He considered that the correct approach was to proceed on the basis of the declaration in terms of s 54(4)(b) of the Bankruptcy (Scotland) Act 1985 and the report in terms of section 54(5).

The court could consider not only whether the deferment was sought for a specific purpose, but also past events in concluding that the bankrupt was not entitled to discharge. Non-compliance with the provisions for disclosure and co-operation might be factors to consider. The right to discharge had to be balanced against this obligation for compliance.

Sheriff Holligan considered that most such applications could be determined on the basis of the declaration and the trustee’s report, with evidence only being required in exceptional instances.

Lay representation

In Homebank Financial Services v Hain, Dunfermline Sheriff Court, 19 January 2010 (posted Scottish Courts website 25 October 2011), the issue before Sheriff Way was whether a limited company could prepare a small claim summons at its own hand and present it for warranting.

Sheriff Way considered that a court was entitled to have a natural person responsible for drafting of court documents and conducting litigation, but that person could be an authorised lay representative. Thus any lay representative should be named in the relevant section of a small claim (or summary cause) summons if these documents have been drafted by that person for a legal entity. While small claim rule 2.1 referred to an authorised lay representative being able to do anything an individual could do, Sheriff Way did not consider that “individual” restricted its operation to litigants who were natural persons.

Party litigants

In Thompson v Harris, Edinburgh Sheriff Court, 2 September 2011, one point taken by the pursuer, a party litigant, was that the sheriff presiding at the proof had interrupted frequently and had been brusque generally.

In rejecting this ground of appeal, Sheriff Principal Stephen noted that some of the interruptions had been made in an effort to assist the pursuer. Others were the result of attempts to focus the pursuer’s presentation. Such interruptions were perfectly permissible and indeed were important in the managing of court time. Further admonitions to be quiet were not objectionable when a party litigant was guilty of interrupting others. A sheriff was required to control and manage proceedings.

Expenses

In Graham v Advocate General for Scotland 2011 SLT (Sh Ct) 141 a note of objections was taken against a decision by the auditor not to allow the audit fee as a judicial expense. The pursuer’s account of expenses submitted for taxation was reduced by 27%, although the taxed figure exceeded by about £1,000 the figure offered by the defenders. Sheriff McKenzie decided that the auditor had discretion as to whether to award the audit fee and in light of the significant reduction achieved by taxation it was perfectly within his discretion to refuse to do so.

In this issue

- The role for pro bono

- Rectifying trusts – a Scottish perspective

- Squeezing capital claims

- The many faces of mortgage fraud

- Welcome break or cause for concern?

- Opinion

- Reading for pleasure

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Beware what you register

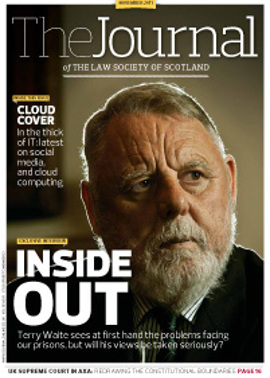

- Justice inside and out

- Auto-enrolment: are you prepared?

- Power and authority

- Refining the message

- Seeing through the cloud

- Don't drag out child cases

- Up to the job?

- Permanence changes

- LGPS: sea change again

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- ILG takes on risk

- Real burdens revived

- Practical limitations

- CPD: how to comply

- Law reform update

- The learning curve

- Ask Ash

- Inside story