Ademption and powers of attorney

For some time, powers of attorney have been at the centre of uncertainty in relation to the operation of the doctrine of ademption. Part of that uncertainty is now removed by the decision of Lord Tyre in Turner (Gordon’s Executor) v Turner [2012] CSOH 41; 2012 GWD 10-197 (7 March 2012).

What is ademption?

Ademption is a doctrine that causes special bequests to fail. Sometimes classified as a form of revocation, it depends not on the intention of the testator, but on the existence of the thing bequeathed. Albeit familiar to private client lawyers, it is, at least in my experience, less well known than it should be by lawyers practising in other areas of law, such as the sale of houses, incorporation of business etc. This lack of awareness is remarkable in one sense because, where the client is an individual, ademption is frequently a consequence of these lifetime transactions.

The law of succession operates on the property within the estate of the deceased as at the date of death. The corollary of this fundamental principle is the doctrine of ademption. This doctrine normally provides that a special bequest (such as “my house at 100 High Street, Stonehaven”) will fail if the thing bequeathed does not form part of the estate of the deceased as at death. The decision in Turner, as we shall see below, amounts to a narrow exception to this general rule.

Ademption and attorneys

Turner v Turner is not authority for a proposition that ademption of a specific bequest will not occur just because (a) the testator has granted a power of attorney, or (b) the disposition of the bequeathed subjects is executed by an attorney for the testator. In many cases where a client has prudently granted a power of attorney, that client may still retain capacity to grant a disposition. Even where the power of attorney is granted in the context of a prospective failure of the client’s mental facilities, in some cases, out of respect for the client who still retains sufficient capacity, a solicitor after concluding missives may give the client “his place” and have him sign the disposition.

The fact that a power of attorney has been signed does not bereave the client of the capacity to sign that disposition (opinion, para 12). Where a disposition is granted in this way, ademption may follow in respect of an existing special bequest of the subjects disponed. Another variant occurs where the testator retains capacity to grant the disposition but chooses to have the disposition executed by an attorney acting on his behalf. In such a case ademption of a special bequest of the subjects disponed will be the result of the conveyance.

One should recall at this stage that missives are invariably entered into by solicitors on behalf of clients. However, ademption does not occur at the stage of conclusion of missives, as the subjects of sale still form part of the estate of the testator. All that has been changed is the creation of a new obligation to convey and a correlative right to receive the price. This composite of assets and rights is collectively known as “conversion” (Gretton & Steven, Property, Trusts and Succession (2009), para 25.43).

The litigation in Turner did involve a disposition granted by an attorney. What was different was that the client was unable to attend to her affairs at the time of the grant of that disposition.

The facts in Turner v Turner

The facts follow a pattern that will be familiar to solicitors dealing with private client matters. On 17 April 1996 Miss Isabella Coutts Gordon granted a power of attorney to her solicitor. In terms of that deed she conferred on her attorney various powers, including the power to sell any part of her estate, heritable or moveable, ratified future acts and supplemented this with a declaration that all acts done by her attorney would be as valid and binding as if done or granted by herself.

Subsequently she executed a will appointing the same solicitor and another party as her trustees and executors. The will contained a special bequest of her house at 33 Dunnottar Avenue, Stonehaven. About 2001, Miss Gordon became incapable of managing her own affairs and moved to a nursing home, in which she remained resident until her death on 27 January 2008. At her death the special bequest remained unaltered.

Despite the mental incapacity of the testatrix, the power of attorney continued to have effect: Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990, s 71; Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000, s 15 and sched 4, para 4(2). In or around September 2001, the attorney arranged for the house to be sold at a price of £71,250. All the parties agreed that this sale was a prudent act of administration, having regard to the disadvantage of leaving the house empty. The sale of the house was not necessary because Miss Gordon, if sui juris, would not have been constrained to sell the property.

The issue that arose for decision in the litigation was this: was the special bequest of the house adeemed by the sale carried out by the attorney? The court’s answer was that the bequest was not adeemed and the beneficiary was entitled to the proceeds of the sale of the house. In addition, since the house was sold more than 10 years prior to the litigation, the beneficiary was entitled to fruits of the investment of those proceeds in the intervening period.

Basis of the decision

A transaction carried out by an attorney for a party who is unable to act for himself is to be regarded as analogous to a transaction carried out, under pre-2000 law, by a curator bonis appointed to manage the affairs of a person unable to manage his or her affairs. (The office of curator bonis was rendered obsolete by the 2000 Act, s 80 and sched 4.) A disposition by such a person cannot alter the succession to the ward, and will cause ademption only if the transaction was necessary and would have been required to have been carried out by the testator if sui juris. Where it is carried out only as an act of prudent administration, ademption does not result and the beneficiary remains entitled to the proceeds of sale as a surrogatum for the thing sold.

Future practice

Lord Tyre’s decision is to be welcomed as providing clarity where previously there was doubt. Those relying on the Turner case will require to ensure that the proceeds of the sale of a specially bequeathed item are invested suitably and are identifiable. A separate account may be the best way of dealing with this.

More generally, the use of anti-ademption devices or strategies will continue. The will in the Turner case could have provided that the special bequest extended to “the house and the proceeds thereof, if sold”. Given the facts in Turner, this would have achieved much the same outcome. In other cases clients may decide to avoid entirely the use of special bequests.

In this issue

- Data protection principles and family practice

- Data protection: another generation

- No guarantee of easy recovery

- Forced marriage: alive to the issue

- Mediation: business as usual?

- Electronic payments and electronic money

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Caution the souvenir hunters

- Together we thrive

- But you said...

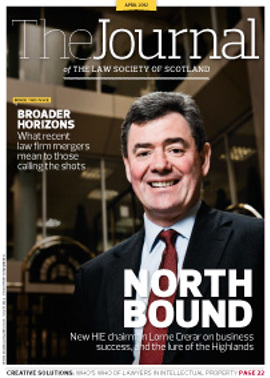

- Heart in the Highlands

- Cut the lockup cost

- Who's who in intellectual property

- Taking liberties with bail

- Personal licences: a need for review?

- TUPE: fair or unfair for staff?

- 10%: a real gain?

- Renovating home PDRs

- Ademption and powers of attorney

- Working group to take forward ILG review

- Law reform roundup

- From the Brussels office

- Feedback, take 2

- Chinks in your defences?

- Business checklist

- Ask Ash