But you said...

“…the starting point in all criminal trials in Scotland remains parole evidence. To put a written statement before a witness for the purpose of leading him in chief is clearly unacceptable and before, therefore, reference is made to any written statement, the purpose of doing so should be made clear, whether it be a challenge under s 263(4) of the 1995 Act, an intention to invoke Jamieson (No 2) or… an invocation of the discrete provisions of s 260” (per Lord Marnoch in Hughes v HM Advocate [2009] HCJAC 35, para 13).

Referring a witness to a prior statement is commonly encountered in the criminal courts. According to the appeal court in A v HM Advocate [2012] HCJAC 29, there is a lack of understanding of the processes involved, and a regular feature is “that the purpose is not clearly identified at the outset and that the examination proceeds in a fairly haphazard way” (Lord Bonomy, para 1).

To put a previous statement to a witness is an exception to the normal rule that hearsay is inadmissible. This article seeks to recognise the different routes both at common law and in statute where departure from the rule can occur, and explores why confusion can arise.

Memory failings

In Jamieson v HM Advocate (No 2) 1994 SCCR 610, a witness stated in court that she could not remember details of an assault. She accepted having made a statement about the incident to a police officer and that the statement she gave was true. The terms of the statement were not put to her in detail. She was not challenged in cross examination. Evidence was then led from the police officer who took the statement regarding its content. The accused appealed on the ground that the officer’s evidence was inadmissible hearsay.

The court applied the principle in Muldoon v Herron 1970 JC 30, declaring that it was not simply confined to identification evidence. The court held that there were two primary sources of evidence, namely the officer’s evidence as to what the witness had said in her statement, and the witness’s evidence that she had made a statement and that what she had said was true.

Accordingly, the witness who cannot recollect events when testifying can “adopt” or, as said in Jamieson, “incorporate” the prior statement into their evidence. If the witness accepts that the prior statement contained the truth, its content can be spoken to by another witness who heard its making. The statement can then be treated as evidence of the truth of its contents.

Prior inconsistencies

Quite often a witness remembers an incident but gives evidence which differs from a previous statement. Since the Evidence (Scotland) Act 1852, it has been permissible to examine a witness about a prior inconsistent statement: see now Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995, s 263(4).

Previous inconsistent statements can be used to test whether a witness is lying in court. The witness can be questioned on whether they previously made a statement which differs from their evidence at trial. Evidence may then be led to prove that the witness made a different statement on the occasion specified. The witness must first be asked if they have made an earlier statement which contradicts their evidence on oath. Only then can evidence of the previous statement be led (McTaggart v HM Advocate 1934 JC 33).

Often, a witness will eventually decide to give evidence which is consistent with their previous statement. Does that lead to the witness adopting the previous statement and it becoming evidence of the truth of its contents? The traditional view would be that the previous statement is not admissible as evidence of the facts to which it refers. According to the reasoning of Lord Bonomy in A, also adopted by Lord Emslie, the section permits a witness to be examined about an inconsistent statement “with a view to either eliciting the truth or discrediting him”.

“Any prior statement”

The practitioner should carefully read the terms of s 260 of the 1995 Act.

In terms of s 260, where a witness gives evidence in criminal proceedings, any prior statement by the witness shall be admissible as evidence of any matter stated in it of which direct oral evidence by him would be admissible in those proceedings. The statement is only admissible if (a) it is contained in a document; (b) the witness, in giving evidence, indicates that the statement was made by him and that he adopts it as his evidence; and (c) at the time the statement was made, the person who made it would have been a competent witness in the proceedings. A prior statement is one which “but for the provisions of this section, would not be admissible as evidence of any matter stated in it” (s 260(3)).

By s 260(4), the prior statement would appear only to be admissible if it is sufficiently authenticated. The Act of Adjournal (Criminal Procedure Rules) 1996 provides the form of certification. It is the person who prepares the statement, not the maker of the statement, who signs the certificate.

The original annotated statute referred to this section as having been “perceptibly influenced” by Jamieson. Is it, or is it not, simply the statutory equivalent of Jamieson? In Hemming v HM Advocate 1997 SCCR 257, Lord Osborne, delivering the opinion of the court, confessed to having some difficulty in understanding what the precise purpose of s 260 was supposed to be, having regard to Jamieson. The court in A stated that although the section appeared very similar to the principle in Jamieson, it was not the same, and provided for different circumstances. However, it was not the time to attempt an exhaustive exegesis. This had also been the position of the court in Hughes v HM Advocate [2009] HCJAC 35.

The criticism in A was that, often, the reason for resorting to a statement is unclear and “the examination of witnesses appears at times to be conducted on the basis either that statement-generated evidence can be reviewed at the close of the evidence and a decision then made on the use or uses to which it may be put, or that it can be left to the trial judge to give appropriate directions to the jury on how to treat it” (Lord Bonomy, para 6).

Niblock v HM Advocate 2010 SCCR 337 has been cited in the more recent cases as an example of the correct approach when prior witness statements are being referred to.

Without specifically answering whether the witness in Niblock had adopted his earlier statement, the court held that in all cases where a witness could legitimately be referred to a prior statement, it was for the judge to give the jury a specific direction as to the purpose of the Crown’s reliance on the statement and a direction as to its evidential significance. Accordingly, the basis upon which the witness is referred to a prior statement must be made clear. Clarity at that point allows for clear directions to the jury.

Useful reference?

The Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 brings in two further provisions of note.

A new s 261A of the 1995 Act (2010 Act, s 85(2)) provides for the use of a prior statement during trial. Where a witness is giving evidence and has made a prior statement, provided that both the prosecutor and the accused (or his representative) have seen or had an opportunity to see the statement, the court may allow the witness to refer to the statement while the witness is giving evidence. Does this section allow use of an aide-mémoire? Where does this provision sit with the common law and statutory provisions referred to above? It provides additional procedure to enable a witness presumably to adopt or challenge his prior statement, by allowing access to the statement with the court’s leave.

Separately, and of greater importance, is s 54 of the 2010 Act. Where, in the course of a criminal investigation, a witness has made a statement in relation to that matter, if the statement is contained in a document, and the witness is likely to be cited to give evidence in criminal proceedings, then, before the witness gives evidence, the prosecutor may either give the witness a copy of the statement or make the statement available for inspection by the witness at a reasonable time and place.

The stated policy objective is to ensure fairness for witnesses giving evidence. It has been pointed out that often the only person not to have seen their statement before trial is the civilian witness. After all, the police witness has been able for years to refresh his memory via his notebook before he steps into the witness box (see generally, policy memorandum to the bill, paras 200-208). But how will this operate in practice? Will the day come when a witness is able to refresh his memory while waiting in the witness room?

Confusion of purposes

Confusion and uncertainty arise because of the variety of provisions and the differing purposes for which prior inconsistent statements, or the forgotten statement, can be introduced. To what extent the use of prior statements introduces otherwise inadmissible hearsay is also questionable (consider the reasoning in Jamieson, and also see Lord Emslie in A, para 29). It is perhaps the concept, and the mechanics, of “adoption” that can lead to possible misdirection that “adoption” equates to an unshakeable or unchallengeable truth.

Lord Emslie’s judgment in A provides the most detailed judicial consideration of s 260 to date. In favouring a broad and flexible approach to the application of Jamieson, s 260 or s 263, his Lordship concluded: “Where, as is all too often the case, reluctant witnesses go to extreme lengths in an attempt to avoid disclosing what they know, there is… every reason why jurors, familiar with human nature, should be entitled to attach weight to what such witnesses may, however briefly, be prepared to accept having said at a time when they were (again on their own admission) doing their best to tell the truth [emphasis in original]. In some cases that may be the closest a witness comes to an account consistent with his or her oath… it would be a matter of real concern if, on unnecessarily restrictive grounds, the scope for allowing juries to access, and perhaps accept, flashes of what may be the real truth were to be cut down to any degree. It must, in the end, be for the jury to determine whether a prior statement has been sufficiently ‘adopted’ so as to become part of the substantive evidence in the case.”

In summary, clear judicial interpretation of the use and extent of s 260 is awaited. The interaction of the various provisions remains unclear. The required mechanics of “adoption” and the actual degree of formality demanded have yet to be explored and tested by the courts.

In this issue

- Data protection principles and family practice

- Data protection: another generation

- No guarantee of easy recovery

- Forced marriage: alive to the issue

- Mediation: business as usual?

- Electronic payments and electronic money

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Caution the souvenir hunters

- Together we thrive

- But you said...

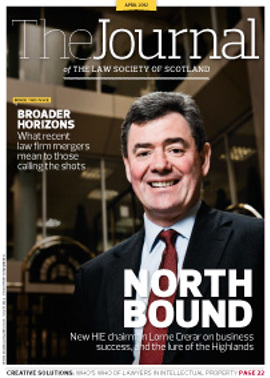

- Heart in the Highlands

- Cut the lockup cost

- Who's who in intellectual property

- Taking liberties with bail

- Personal licences: a need for review?

- TUPE: fair or unfair for staff?

- 10%: a real gain?

- Renovating home PDRs

- Ademption and powers of attorney

- Working group to take forward ILG review

- Law reform roundup

- From the Brussels office

- Feedback, take 2

- Chinks in your defences?

- Business checklist

- Ask Ash