Forced marriage: alive to the issue

“Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.” (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 16(2))

The social stigmatisation of domestic abuse in Scotland over the past two decades has rapidly shifted public perception from viewing domestic violence as something of a private matter, to that of a crime. But in relation to forced marriage specifically, there has been a traditional reluctance on the part of the legislature to intervene in this arena. Following the introduction of the Forced Marriage etc (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Act 2011, the Scottish Government has now issued multi-agency practice guidelines to direct professionals who might come into contact with a person at risk of forced marriage. Within the legal profession, it is most likely to be family lawyers and solicitors versed in immigration rights who will encounter this multifaceted issue.

From the outset, the statutory guidelines reinforce that all practitioners must actively embrace the “one chance” rule, that you may only have one chance to speak to a potential victim. Thus all practitioners need to be aware of their responsibilities to possible victims of forced marriage – if a victim leaves without being offered support and accurate advice, that one chance might be wasted.

A combination of cultural misconceptions and an apparent reluctance to trespass into “family” matters in relation to arrangements for marriage – typically made within BME communities in Scotland – evidently culminated in the issue of forced marriage not being fully addressed by Scots law until now. Forced marriage is a peculiar type of domestic abuse because close and extended family members, as well as in-laws and the wider community, are often involved. It is not a crime that is often perpetrated by one individual acting alone.

As well as there often being more than one perpetrator, there is usually the additional problem that, due to cultural or religious traditions, those involved do not see anything wrong in their actions or feel any pressure or stigma from the wider community. Furthermore, influenced by notions of family dishonour, perpetrators themselves are often trapped between the victim’s feelings and the expectations of the community.

A legal response

Of course, it has always (at least in recent decades) been the case that where a person has been forced against his or her will to give “full and free consent” to marriage, that marriage is void (Marriage (Scotland) Act 1977), with the remedy being to seek a declarator of nullity of marriage. However, obtaining such a declarator is a retrospective remedy that cannot provide protection from harm in the first place. It is a legal tool for the purpose of reacting to void marriages, rather than serving as a tangible form of protection against forced marriage in Scotland.

Accordingly, prior to the introduction of the Forced Marriage etc (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Act 2011, the existing provisions in Scots law concerning validity of marriage did little to protect those atrisk of being forced into entering a marriage against their will, except to the extent that perhaps, in their overarching symbolism, such provisions purported to serve as a deterrent.

On 27 April 2011 things changed. The Forced Marriage etc (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Act 2011, having been passed by the Scottish Parliament, received royal assent, coming into force on 28 November 2011. The primary aims of the Act are twofold: to protect people from being forced to marry without their free and full consent; and to protect those who have already been forced into marriage without their consent.

“Forced marriage” is defined in s 1 of the Act as being a marriage entered into by a party who has been “forced” to enter into it without their own “free and full” consent.

“Force” is defined in s 2 as including verbal or psychological conduct as well as physical behaviour, which is particularly important given the unique cultural context in which such marriages tend to occur. It is often psychological and emotional pressure, from parents, other family members and the wider community, which results in the victim finding themselves in a position in which they are under enormous cultural pressure to conform to the wishes of both family and community.

Interestingly, the Act does not extend to civil partnerships. However, this is probably due to the fact that the social circumstances that lead to parents forcing their children into marriage against their will are less likely to be replicated in relation to civil partnerships. In any event, it is possible for the Scottish ministers to apply the provisions of the Act by order to civil partnerships.

A new legal tool

The Act purports to achieve its aim of protecting people from forced marriage through the introduction of a new legal tool – the forced marriage protection order, or “FMPO”. FMPOs are granted under s 1 and may contain any prohibitions, restrictions or requirements as the court considers appropriate for the purpose of the order. Applications are to be made to the Court of Session or to the sheriff in whose sheriffdom the protected person is ordinarily resident.

On the face of the wording of the Act, the scope of the FMPO appears capable of being very wide indeed. It is reasonable to assume that it was the deliberate intention of the Scottish Parliament to define these new legal instruments in such a way so as to enable them to be potentially very wide in their application. This is a good thing. Any legal tool aimed at responding prospectively to the complex problem of forced marriage must be capable of covering the multitude of issues that might arise in a situation involving this unique and peculiar form of abuse.

Accordingly, FMPOs maycontain restrictions in relation to conduct outside Scotland, and they can also compel a person who is implicated in making someone enter into a forced marriage to come to court and disclose the whereabouts of the protected person, or make them refrain from taking the protected person to certain places, or submit to the court passports or other documents.

Overall, the general tone of the Act is commendable in terms of the overarching message it conveys. For instance it contains provisions which clarify and reinforce the authority of the sheriff court to declare invalid such marriages. It also creates a new criminal offence for a person to breach the terms of a FMPO, whilst outlining in black and white the duty of statutory agencies to respond appropriately to forced marriage. It is evident that the Act attempts to stigmatise forced marriage and communicate clearly the message that it will not be tolerated in Scotland.

However, the true extent to which FMPOs will be applied for in practice remains to be seen. Although, in theory, they are potentially a very effective protective tool, in reality it is likely to be down to the imagination of social workers, teachers and agency workers to bring these orders to life. The protected person at risk of entering into a forced marriage is unlikely to apply to the court for a FMPO. It is equally unlikely that a third party who is close to the protected person will be in such a position either.

Thus, despite s 4 of the 2011 Act allowing for different categories of persons to apply for a FMPO, such as the victim or anyone on behalf of the victim (as long as the latter obtains the court’s permission to make an application), or procurators fiscal acting under the authority of the Lord Advocate (who may apply on behalf of a victim but do not need to seek leave of the court), in reality it is likely to be the work of the “relevant third parties” such as the local authority, including teachers and social workers, who will apply for them. In practice, the FMPO will be a tool for vigilant agency and support workers to respond to situations where women (or men: we cannot say if it is a ‘gendered’ crime, as there is no reliable source of information which captures the cases involving male victims of forced marriage in Scotland) with whom they come into contact are at risk. Anyone else can apply for a FMPO but they must have leave of the court to do so. The statutory guidelines highlight that this is to ensure that any third party is acting in the best interests of the victim.

Some practical guidance

Whilst the UK has special agreements dealing with child abduction with Pakistan (Anglo-Pakistan Protocol) and Egypt (Cairo Declaration), practitioners need to know what to do on a practical level if it is suspected that a child or adult victim is at risk of being taken abroad. The Scottish Government guidance accordingly draws attention to the Forced Marriage Unit (“FMU”) – a joint FCO and Home Office unit which offers advice to anyone in the UK, regardless of nationality, and offers specific assistance to British nationals facing forced marriage abroad.

The FMU works with Government departments, statutory agencies and voluntary organisations and also runs an outreach programme. It offers a casework service and can assist British nationals facing forced marriage abroad by helping them to a place of safety. In particular, the FMU can assist a British national’s return to the UK by providing emergency travel documents, helping to arrange flights and, if possible, arranging temporary accommodation whilst the victim is overseas.

The guidance highlights that practitioners should contact the FMU if it is suspected that a victim has been, or is being, taken out of Scotland, or abroad. It can assist in alerting the police and authorities at points of departure so that the victim and those accompanying her can be detained and prevented from leaving the UK.

The guidance also provides that practitioners must make it clear to a potential victim if they are planning to intervene, particularly if this involves making an application for a FMPO. It highlights that this is particularly important if the victim has indicated that she does not want to take any legal action. As solicitors, we have a professional responsibility when dealing with adults at risk or with children to act in their best interests.

The guidelines stress that whether to apply for an order will inevitably involve concerns such as a victim’s wish to remain anonymous, as well as the potential risks posed to the victim by the process of applying for an order. For instance, applying for a FMPO might alert the family where the victim is overseas. It is also highlighted that interim orders are available to provide immediate protection prior to a full order being made. Applications for these should be made to the sheriff court in whose sheriffdom the victim normally resides – but if the victim ordinarily lives outside Scotland, the application should be made to the sheriff of Lothian & Borders in Edinburgh.

The Scottish Government guidance further emphasises that if a victim decides that they no longer wish for an order to be made, it will be crucial to ensure that they are withdrawing of their own free will and not as a result of coercion. All practitioners have to ensure that they abide by their legal obligation to act in situations where an adult or child is at risk of harm.

The guidance also provides further practical advice for practitioners dealing with victims of forced marriage – for instance in respect of the use of special measures in court. It is advised that the victim’s views and wishes on this matter should be ascertained and that “superficial judgments” on a victim’s “capability” based on one’s own observations should be resisted. The guidelines also stress the importance of making extra arrangements to support the victim, such as visiting the court in advance to familiarise herself with it.

In respect of interviewing, the guidance stresses that since victims are likely to be anxious or distressed, it is particularly important that interviews take place in a private and secure setting free from interruptions. If it is necessary for a translator to be used when interviewing the woman, it should be ensured that this party is an independent professional – never a family member or apparent “friend”, who may be a family member masquerading as support. It is also advised that the woman may be unwilling to speak to a male practitioner alone.

Lastly, the guidance advises that care must be taken to ensure whether the individual can be contacted safely at work, school or through a trusted friend, sibling or organisation. It suggests that an agreed code word could be used to ensure that when using telephone contact you are speaking to the right person. This is because involving families in cases of forced marriage can be particularly dangerous. The family may not only punish the woman for seeking help but also deny that they are forcing her to marry, expedite any travel arrangements, and bring forward the marriage.

The new status of forced marriage in Scotland

The introduction of the Forced Marriage etc (Protection and Jurisdiction) (Scotland) Act 2011 is a significant step in terms of conveying the message that Scots law will respond to the problem of forced marriage from the outset. It communicates quite starkly that forced marriage is no longer a private “family issue”, allowing for legal intervention in terms of the FMPO where someone is at riskof being forced to enter into marriage against their will. The Government’s guidelines in relation to forced marriage go some way to ensuring that all professionals likely to encounter it will have access to the advice they will require to deal with it sensitively.

Ultimately, the victim herself will often not have a voice. She is unlikely to be in a position whereby she can apply for a FMPO herself. Those around her are either likely to be unaware of the abuse, or involved in it themselves.

On paper, the 2011 Act is a significant development in terms of responding to forced marriage in Scots law. However, the true success of the FMPO ultimately depends on it being used effectively and sensibly by the relevant professionals as a new weapon in their armoury.

The legal tool is now there to respond to forced marriage before it can occur. It is up to those who have the oversight to apply for it to use it, making use of the available Government guidelines. At the very least, the Act and the creation of the FMPO will help to shift public perception of forced marriage as a family matter to it being recognised unequivocally as a form of domestic violence against women.

In this issue

- Data protection principles and family practice

- Data protection: another generation

- No guarantee of easy recovery

- Forced marriage: alive to the issue

- Mediation: business as usual?

- Electronic payments and electronic money

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Caution the souvenir hunters

- Together we thrive

- But you said...

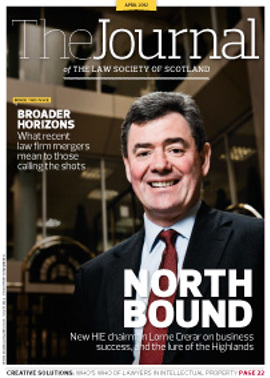

- Heart in the Highlands

- Cut the lockup cost

- Who's who in intellectual property

- Taking liberties with bail

- Personal licences: a need for review?

- TUPE: fair or unfair for staff?

- 10%: a real gain?

- Renovating home PDRs

- Ademption and powers of attorney

- Working group to take forward ILG review

- Law reform roundup

- From the Brussels office

- Feedback, take 2

- Chinks in your defences?

- Business checklist

- Ask Ash