Mediation: business as usual?

Like many mediators I am conscious of the risk of overselling. However, in spite of having a reasonably high profile, and even its own chapter in the Gill Review, when it comes to the Scottish lawyer’s bread and butter work mediation remains one of the more neglected forms of dispute resolution. It is worth asking why, and exploring whether and how this may change.

This paper is in three sections: two questions and a “mythbuster”. I start with the business question: why does mediation make good business sense? Then I turn to the “value added” question: what does mediation contribute to dispute resolution? And finally I challenge three popular myths about mediation. I draw on two recent publications, both of which indicate profound change in the way that mediation is conceptualised by the legal profession. They are Mediation Advocacy, by Andrew Goodman, and Mediation: A Practical Guide for Lawyers, by Marjorie Mantle.

Why does mediation make good business sense?

I could frame this in a less subtle way by asking, “How can sharing my fee with a mediator increase my fee-earning capacity?” Marjorie Mantle sees it in simple terms: “your fee income can increase and your client base grow when mediation is used appropriately” (Mediation: A Practical Guide for Lawyers, 11). It is not unreasonable to ask how. I focus on two areas: attracting clients and representing them in mediation itself.

Attracting clients

Many of us will know that clients are often the last people to seek mediation. The suggestion of a collaborative approach can be met with stiff resistance, e.g. “Are you saying we have a weak case?” (sometimes the answer is yes); or even “Whose side are you on?”

We need to draw a distinction here between what Mark Galanter has termed “repeat players” and “one-shotters” (“Why the ‘Haves’ Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change”, Law and Society Review, 1974). I will return to one-shotters (those in courts or tribunals for the first time) shortly, but many of our clients are in fact repeat players. Whether from business or the public sector these clients are sophisticated, informed and acutely conscious of the increasing cost of disputes.

Rather than reacting to disputes on an ad hoc basis, mediation can be presented to these clients as part of a comprehensive risk management approach. In this way lawyer and client jointly design a system that takes into account the circumstances, risks and likely costs at each stage, from negotiation, through mediation to court action. Mediation thus becomes part of a rational and proportionate strategy to deal with matters that can be both troublesome and time-consuming for clients. And the lawyer expands his or her range of services to include “dispute resolution adviser”.

Another dimension of the mediation choice relates as much to one-shotters as to repeat players. This comes through strongly in recent Canadian research: while lawyers are trained to narrow problems to their legally relevant components, clients’ concerns are often much wider, including the business, time and emotional costs of a dispute. Tamara Relis found that clients on both sides of disputes appreciated the non-legal benefits, while lawyers seemed curiously unaware of this. Mediation can expand solicitors’ range by enabling these “non-legal” concerns to be addressed while still working towards a settlement: “What pervaded disputants’ talk on mediation agendas was their wanting to directly communicate their perspectives, be heard, seen, and understood” (Tamara Relis, Perceptions in Litigation and Mediation: Lawyers, Defendants, Plaintiffs, and Gendered Parties, 153).

Finally, it goes without saying that satisfied clients are good for business. If mediation helps clients resolve disputes in a way that is quick, inexpensive and humane, they will return to the solicitor who recommended the process. Satisfied clients also talk to their friends, bringing potential new clients with them.

Mediation advocacy

It is a mistake to see mediation as an alternative to legal representation. It is more accurate to describe it as an alternative to litigation. Lawyers have always made a good proportion of their living by representing clients in litigation: equally, clients need effective representation in mediation. Where the value of a claim is modest, clients may choose not to have a lawyer present during mediation. However, most commercial, employment and personal injury matters are of sufficient value and gravity to require effective advocacy.

So what is “mediation advocacy”? Andrew Goodman (Mediation Advocacy (2nd ed), 24) lays out five roles:

- deciding to and persuading others to engage in the process;

- choosing the mediator;

- controlling the pre-mediation element;

- team-leading at the mediation itself;

- securing a working settlement.

At each stage the lawyer plays a crucial role in managing the process. With mediation still at a relatively early stage in its development, choosing the mediator can prove more difficult here than in England & Wales. Goodman provides advice for weighing up whether or not a legal qualification is essential: “whilst you and your opposite number may be conscious of the legal parameters and merits of the dispute, a non-lawyer mediator may have a completely different overview of the settlement objectives of the parties” (p46). Whether this is useful will vary from client to client and case to case, but it certainly requires attention and judgment, underlining another of Goodman’s points: “the selection of your mediator may be the most important decision you make regarding the mediation” (p51).

The conduct of the mediation itself requires a particular set of skills. Goodman suggests that any disadvantages created by lawyers’ training in the adversarial system are more than offset by their skills as exponents of “critical analysis, of problem solving and of communication in circumstances where dynamic change is part of the dispute process and has to be reacted to and catered for” (p18). Lawyers have to be on their toes to represent clients effectively in mediation. Those who excel in this role will quickly develop reputations for effectiveness.

Perhaps this is the ground-breaking idea: lawyers may in the future make a good proportion of their living representing clients in mediation. Not long ago the Faculty of Advocates seemed quite stunned to hear Australian QC Ian Hanger tell us that the Queensland bar makes half its income from ADR. (Those with long memories may recall that Ian Hanger was the original "McKenzie friend" in 1970.) Are we are missing a trick in Scotland?

How does mediation add value?

It is not uncommon to hear lawyers speak warmly of mediation in general, but when asked if they would recommend it for a particular case, respond that they could not see it working. Related to this, lawyers who have developed well honed negotiation skills may struggle to see how a mediator could improve on their outcomes. I suggest three ways in which mediators “add value” to legal disputes.

Procedural justice

Since at least the 1980s, scholars have identified the powerful role of procedural justice. Put simply, substantive justice (what we get) turns out to be less important than procedural justice (how we are treated) in people’s evaluation of how well they have done at the hands of the courts. (For a summary of the research see MacCoun, “Voice, Control, and Belonging: The Double-Edged Sword of Procedural Fairness” [2005] 1 Annual Review of Law and Social Science 171-201.)

A procedurally fair process provides “voice” (the chance to make your case), “being heard” (the belief that the authority figure considers your views); and “respectful treatment” (that is, evenhanded and dignified). This list conveys well the importance to parties of telling their story. One of my students, an experienced family lawyer, reacted to this research by saying that it explained one client’s surprising response. When she and an advocate negotiated what she regarded as “the best possible deal”, he said he was “gutted”. The whole deal had been struck behind closed doors, between legal experts, whose training and commercial inclination teach them to cut to the chase. While the deal had scored highly on substantive terms, the client had no sense of being heard.

So how can mediation help? It provides a forum where parties get to tell their story, even if parts of it are legally irrelevant. And a decent mediator will demonstrate that he has heard and understood that story, while respectful and dignified treatment ought to go without saying.

The net result? Buy-in. When these crucial dimensions of procedural justice are present, parties are more likely to consider the substantive outcome fair. Relis’s study of personal injury mediation found that “93% of plaintiffs and 89% of physicians discussed the importance of expressing themselves and ‘being heard’” (p174). Experienced legal practitioners know how important is their client’s overall sense of justice in settling a case, and how tricky it can be to manage unrealistic expectations. They should not neglect the potential of mediation.

Substantive justice

None of this negates the importance of substantive justice. While lawyers are occasionally sceptical about the capacity of the courts to deliver consistent, predictable and principled decisions, they rightly ask the same questions of mediation. So how does mediation perform?

First, mediators have no option but to seek a fair outcome: because they lack the power to impose decisions, they have to keep asking the question: “Is this acceptable?” And unlike others in the system, they ask that question of both parties, until both parties agree that it is. US scholar John Lande suggests that mediation delivers “high quality consent” (“How Will Lawyering and Mediation Practices Transform Each Other?” 24 Florida State University Law Review (1996-97), 839 at 856). This assertion highlights the importance of an alert and flexible legal adviser (a “mediation advocate”) in assisting parties to assess proposals.

Secondly, mediators bring to the table their own sense of justice. As I discuss in my “mythbuster” section, modern mediators are not passive. Reality testing is a key element in their armoury. For example, a mediator may ask client and solicitor, in private session, “How will this play in court?” The mediator is not saying, “I think this will go badly for you.” But she is alerting the practitioner and client to a potential problem. The practitioner may have it covered: well and good. Often, however, the solicitor may welcome the mediator’s input as a way of managing client expectations: “lawyers may also value mediators for their ability to deflate their own clients’ over-optimistic, dogmatic positions (something that lawyers themselves may have difficulty achieving given their status as client ‘champions’)” (Carrie Menkel-Meadow).

Negotiation agents

Here I borrow from Dick Calkins, veteran law professor and founder of the USA’s largest mooting and mediation competitions. He asserts that the mediator is the only person in the justice system who gets to hear both sides’ weaknesses. For this reason mediation can add value to even the most canny and experienced negotiators.

To use technical terms for a moment, negotiation involves “decision-making under conditions of uncertainty” (Raiffa, The Art and Science of Negotiation: How to Resolve Conflicts and Get the Best Out of Bargaining). In layman’s terms, you don’t know what you don’t know. Each side tends to put on its best face, even in the most civilised of negotiations. And in the adversarial cauldron of negotiation “on the steps of the court” this phenomenon is heightened. While we know our own strengths and weaknesses, when it comes to the other side we are left to guesswork. And there is plenty of evidence that, when it comes to this type of estimation, our guesses are often flawed (see Bazerman and Malhotra, When NOT to Trust Your Gut, for a brief summary of the research).

Put simply, mediation improves negotiation efficiency by increasing the amount of data in play. It is not that mediators unearth people’s weaknesses and then betray them to the other side. A mediator who did this would quickly develop a very poor reputation. Rather, mediators help each party consider its own vulnerabilities as well as strengths, aware that the same process is playing out in the other room. In doing so, mediators can also unearth different but complementary interests: where one party can gain more than the other party loses.

To give a concrete example, it can emerge in the course of an employment mediation that one party no longer wishes reinstatement and is more concerned about securing a reasonable pension. The mediator may already know, from similar private conversations, that the employer is open to considering this. Handled with care, the mediator can explore with each party the range of possible settlements, leading to an outcome that is satisfactory for all but which neither side would have found easy to broach for fear of losing face or looking weak.

To summarise, mediation can add value by enhancing procedural justice (how clients are treated), honing substantive justice (what clients agree, ensuring “high-quality consent”), and expanding negotiation options (ensuring strengths, weaknesses and wider interests are taken into account).

Some popular myths about mediation

Facilitative = passive

This is an enduring idea, for which mediators must bear part of the blame. In essence it holds that their skills and philosophy lead them to be passive witnesses to conflict – holding the jackets while the clients have a “rammy”. If these “touchy feely” mediators intervene at all, it is to ask parties how they are feeling, or simply to convey messages from one side to the other.

More than 15 years ago, US academic Leonard Riskin attempted to shed some light on this by proposing a neat division of mediators into facilitative and evaluative. Facilitative mediators help parties to communicate clearly, understand their options and make their own decisions. They do not provide substantive input. Evaluative mediators, by contrast, assume that the parties are looking for guidance on the likely outcome of the case, and are not shy in providing that guidance (or evaluation) based on their expertise. Riskin’s “Grid for the Perplexed” ([1996] 1 Harvard Negotiation Law Review 7) became a staple of law school mediation courses.

This is too simplistic to describe current UK mediation. While most British mediators would hesitate before providing their evaluation of the case (not least because the presence of experienced lawyers may render this an unwelcome presumption), I believe the most effective and successful mediators could now be described as “activists”. That is to say they lead the process, probing, questioning, summarising, reality testing and, where appropriate, providing information about both procedure and substance. They are pragmatists, at times allowing clients to tell their story, at others breaking into separate rooms to allow shuttle negotiation or even haggling to take place. Towards the end of the mediation they can undergo a personality change, from being the most optimistic person in the room to acting as devil’s advocate to ensure the final agreement is “conflict proof”.

“Mediators have no interest in justice and fairness”

I heard Professor Dame Hazel Genn make this assertion during her Edinburgh Hamlyn Lecture in 2008 (see Irvine, “Mediation and Social Norms: A Response to Dame Hazel Genn” [2009] Family Law 351). I am convinced she is not alone in holding this view. However, I believe it is based on a simple error to which the legal system and those who study it are always susceptible: that of equating justice with law.

As a mediator I wrestle daily with questions of fairness. My clients appear to be making constant judgments about how just or otherwise a proposal or settlement may be. “The law” (or rather, what a court may decide depending on the credibility of the evidence and all the circumstances) is one factor influencing these judgments, but by no means the only one. Here I borrow from American scholar Ellen Waldman who highlights the importance of wider social norms. It is useful to set out her model because it helps to illuminate how decisions are reached in mediation.

According to Waldman, mediators can be ranged on a continuum in terms of their approach to social and legal norms. She calls them “norm-generating”, “norm-educating” and “norm-advocating” mediators.

Put simply, norm-generating mediators leave it up to the parties to decide the basis on which to judge their outcome. If they bring the law into it that is up to them, but the mediator will not interfere. Further along the scale, norm-educating mediators provide information about applicable rules. They work hard to ensure that the parties understand these norms or rules, but ultimately leave it to them to decide whether and how much they govern the outcome. Finally, norm-advocating mediators go a step further in ensuring that agreements comply with the relevant legal, ethical and professional rules.

To return to Professor Genn, while I disagree that mediators are ever disinterested in fairness and justice, those of a norm-generating bent will regard themselves as ethically bound to ensure that it is the parties’ own rules that apply. This approach is common in community mediation, but my fear is that the rhetoric of mediation can make it appear that all mediators fall into this category.

I contend that most if not all commercial mediators can be described as norm-educating. That is, they will take the lead in ensuring that everyone understands the legal and business framework before decisions are made. These mediators are comfortable in working with legal advisers, because they help their clients understand the parameters within which courts or tribunals operate. They usually bring substantive practical and legal expertise and so are able to talk knowledgeably about the pros and cons of different courses of action.

Norm-advocating mediators are probably a rarer breed. Some may go further than others in “reality-testing” people’s choices, but most would stop short of actually insisting that a particular rule is followed. For one thing, who would grant a mediator that authority? What is clear, however, is that those who build a reputation as effective mediators are likely to provide information, guidance, even predictions, while still respecting your client’s right to self-determination.

Mediation disadvantages the less powerful

This idea emerged, probably quite intuitively, soon after mediation’s rediscovery in the 1970s. It holds that, if you remove the procedural protections provided by the adversarial system, those with more power, knowledge or clout will take advantage of the weaker party.

Two responses are worth making. First, this critique could just as easily be applied to any part of the legal system. The case has been made before that those with deeper pockets are at a significant advantage in litigation.

Secondly, mediators have responded to this critique by adapting their practice. As stated above, activist mediators work hard to ensure fairness, in particular procedural fairness. Because mediators cannot impose a decision, their best approach is to ensure that both parties buy in to the process by finding it fair and respectful. The ostensibly “powerful” party (who may not regard themselves as such) can find it unnerving that the other party is given just as long to speak, or helped to make their point as clearly as possible. Empirical evidence suggests that those who have been through mediation tend to rate the fairness of the process highly or very highly, even where they do not get everything they seek (see Ross and Bain, Report on Evaluation of In Court Mediation Schemes in Glasgow and Aberdeen Sheriff Courts (2010) for a recent evaluation of small claims mediation in Scotland).

Business as usual?

I have examined the business case for mediation; described how it can add value for busy lawyers; and attempted to tackle some persistent myths. In the end it is probably a combination of all three (commerce, usefulness and familiarity) that will see mediation being more widely used in future. My own vision would see mediation becoming “business as usual” for Scottish lawyers, a useful and inexpensive form of dispute resolution to offer to clients. It can be conceived as a “settlement ritual”, telescoping months or years of negotiation into a single session and providing clients with the equivalent of their day in court. I finish with another of Mantle’s pithy quotes: “if you fail to discuss mediation with clients, your competitors undoubtedly will”.

References

Max Bazerman and Deepak Malhotra, When NOT to Trust Your Gut (2006): http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/5465.html

Mark Galanter, “Why the ‘Haves’ Come Out Ahead: Speculations on the Limits of Legal Change” Law and Society Review, Volume 9:1 (1974)

Andrew Goodman, Mediation Advocacy (2nd ed) (London: Nova Publishing, 2010)

Charlie Irvine, “Mediation and Social Norms: A Response to Dame Hazel Genn” [2009] Family Law 351-355

John Lande, “How Will Lawyering and Mediation Practices Transform Each Other?” (1996-97) 24 Florida State University Law Review 839-901

Robert MacCoun, “Voice, Control, and Belonging: The Double-Edged Sword of Procedural Fairness” (2005) 1 Annual Review of Law and Social Science 171-201 Available from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1693356

Marjorie Mantle, Mediation: A Practical Guide for Lawyers (Dundee: Dundee University Press, 2011)

Howard Raiffa, The Art and Science of Negotiation: How to Resolve Conflicts and Get the Best Out of Bargaining (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap, 1982)

Tamara Relis, Perceptions in Litigation and Mediation: Lawyers, Defendants, Plaintiffs, and Gendered Parties (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008)

Leonard Riskin “Understanding Mediators’ Orientations, Strategies, and Techniques: A Grid for the Perplexed” (1996) 1 Harvard Negotiation Law Review 7-51

Margaret Ross and Douglas Bain, Report on Evaluation of In Court Mediation Schemes in Glasgow and Aberdeen Sheriff Courts, Scottish Government, Social Research (2010) Available from www.scotland.gov.uk/socialresearch

Waldman, “Identifying the Role of Social Norms in Mediation: A Multiple Model Approach” (1997) 48 Hastings Law Journal 703-769

In this issue

- Data protection principles and family practice

- Data protection: another generation

- No guarantee of easy recovery

- Forced marriage: alive to the issue

- Mediation: business as usual?

- Electronic payments and electronic money

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Caution the souvenir hunters

- Together we thrive

- But you said...

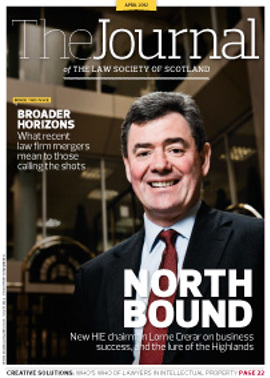

- Heart in the Highlands

- Cut the lockup cost

- Who's who in intellectual property

- Taking liberties with bail

- Personal licences: a need for review?

- TUPE: fair or unfair for staff?

- 10%: a real gain?

- Renovating home PDRs

- Ademption and powers of attorney

- Working group to take forward ILG review

- Law reform roundup

- From the Brussels office

- Feedback, take 2

- Chinks in your defences?

- Business checklist

- Ask Ash